Drawn Home

RMIT University Master of Architecture Graduate Project 2021

Supervisor: Michael Spooner

The Fitzroy Gardens awaits the return of objects collected, stolen, forgotten, doubted, or misunderstood. The garden is marked by mislaid artefacts: a home from elsewhere, the memory of plaster replicas, infrastructure never realised, and the Indigenous landscape that once was. It highlights the problem of repatriated objects that have no end point to their journey, unable to recover a home and perpetually maintaining what is lost.

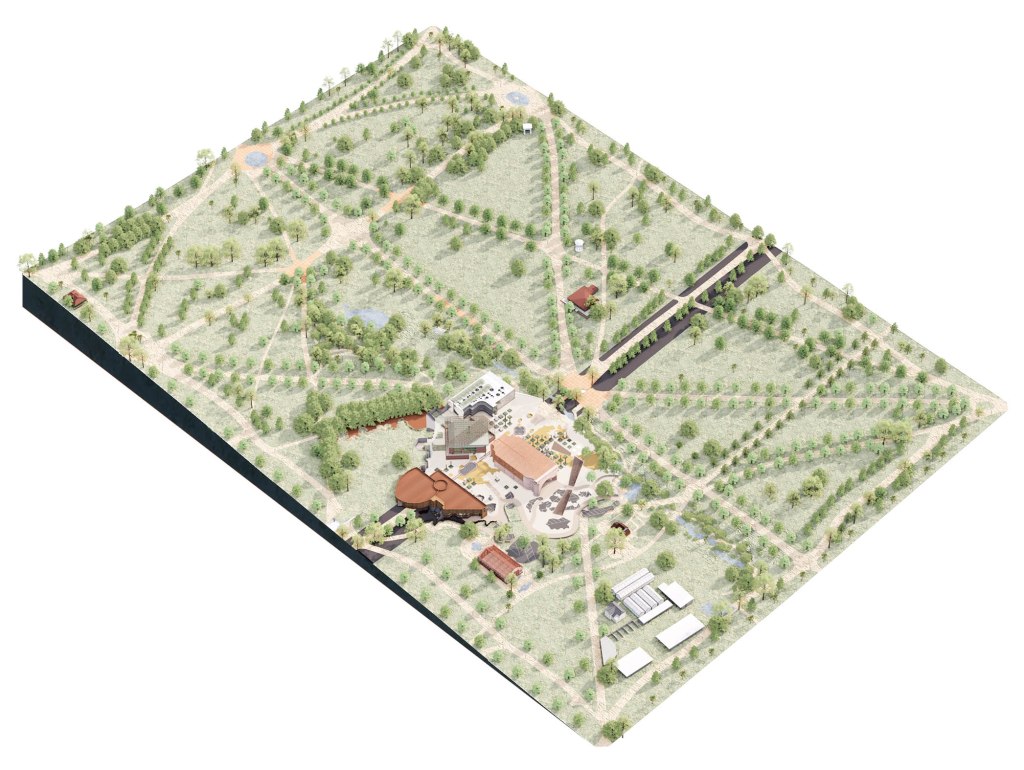

A collection of buildings within this troubled landscape is dedicated to a storeroom holding an infinite array of cultural narratives: an archive awaiting returning gifts, an institution preserving and developing cultural integrity, and a display of catalogues of the imagination. The architecture of each building aims to return what was forgotten, to house all the artefacts so they may lie in repose against one another.

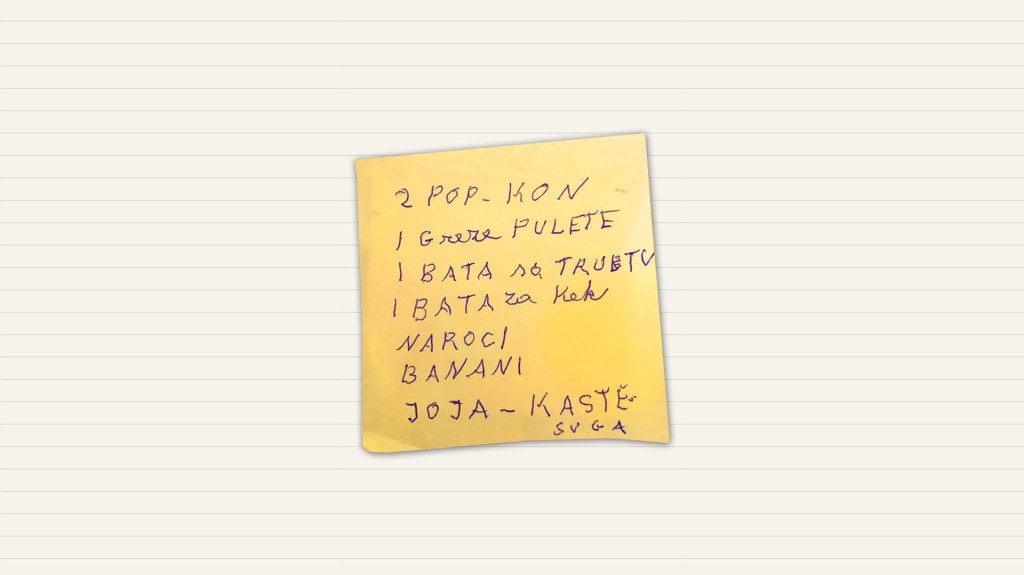

This project is caught in the memory of a tiny island between Croatia, Italy, and Australia. On the fridge in my grandmother’s kitchen hangs a supermarket list that reveals the difficulty of finding oneself between homes: “bata za kek, kokenac, natmeg, raz, sesmi sid.”

PROLOGUE

This story began with my first visit to the land of my heritage, a tiny island caught between Croatia and Italy known as Vis. My grandparents grew up learning a dialect that was not only caught between Italian and Croatian but also between the Croatian dialects of Komiški and Viški, two towns just 8 km apart.

In their 20s, they travelled by boat to Melbourne, hoping to start a new life in a foreign culture, learning the language through spoken word and assumed spelling. Sixty years later, they find themselves speaking a language of ‘broken English’—not quite Croatian or English—a hybrid that remains understood in both languages.

This idea is illustrated by the artefact of a shopping list and a close inspection of the language in the item ‘Bata za Kek’. “Bata” refers to the English “butter,” “za” refers to the Croatian “for,” and “kek” becomes a hybrid of the two languages, taking the K from the Croatian “kolač” and the sound of “cake” in English.

INTRODUCTION

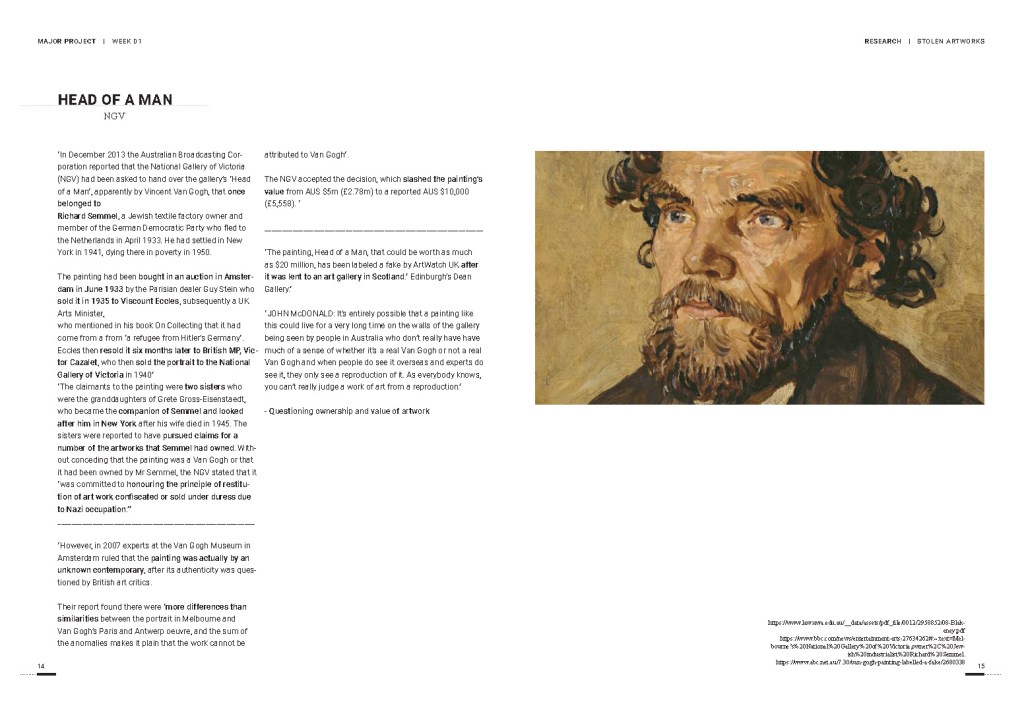

The project began with a potentially endless shopping list of people, communities, objects, and artefacts that can be described through their location between place, language, identity, and custodianship.

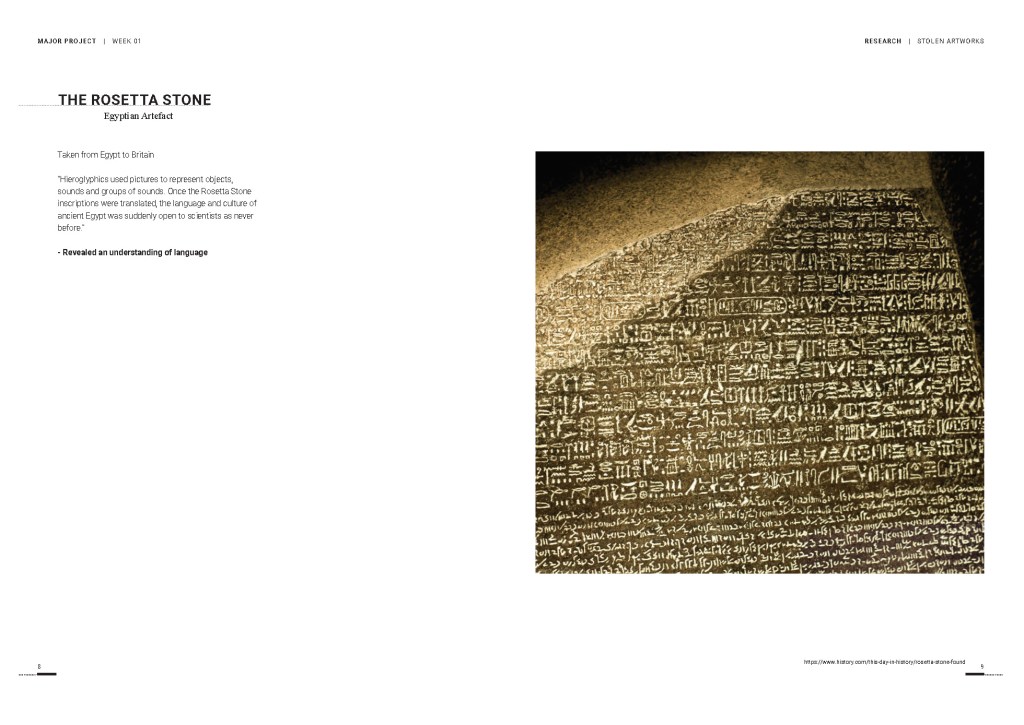

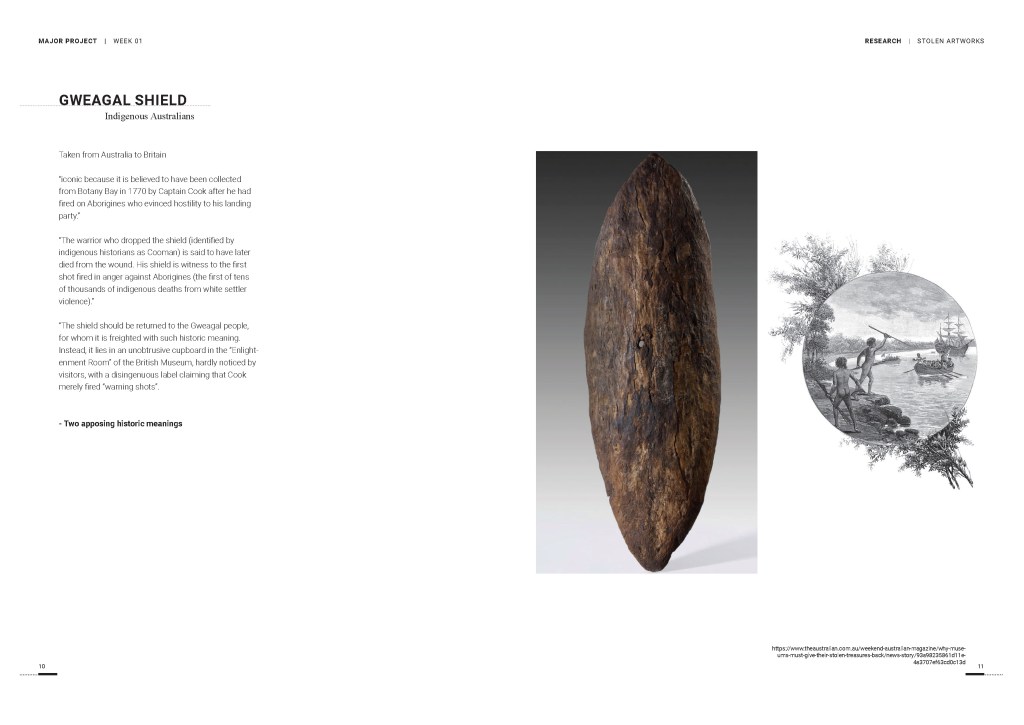

The most significant example is the Gweagal Shield, dropped by Indigenous Australians confronted by Captain Cook’s armed landing at Botany Bay. The shield is held by the British Museum on public display, but with limited investment in describing its significance or the single bullet hole that punctuates its surface, symbolising the violent colonisation of Australia and the ongoing destruction of Indigenous life. The shield exemplifies the continued call for the return of artefacts and remains held by colonial institutions to the custodianship of Indigenous people. The most poignant cases are cultural artefacts located elsewhere, where their loss and unrecorded attribution prevent them from being claimed by their original owners or returned ‘home’ to a custodian.

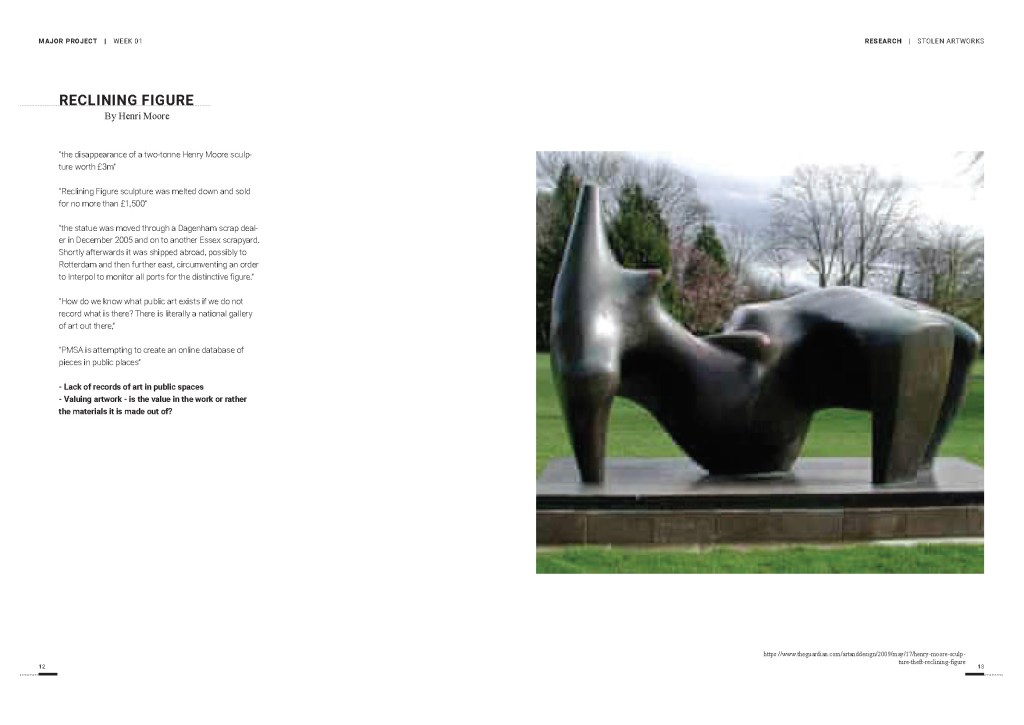

The research also explored how an artefact’s difficult frame of reference could be maintained rather than resolved. A Melbourne example is the ostracised public sculpture by Robert Swann, Vault, which remains excluded from its return to Melbourne City Square. Instead, it appears elsewhere, its yellow paint and folded planes creating an identity that proliferates throughout the city in other forms.

The challenge of repatriation is underscored by objects that may remain unclaimed, the overwhelming number of objects that could be housed, and the impossibility of every object finding a rightful custodian.

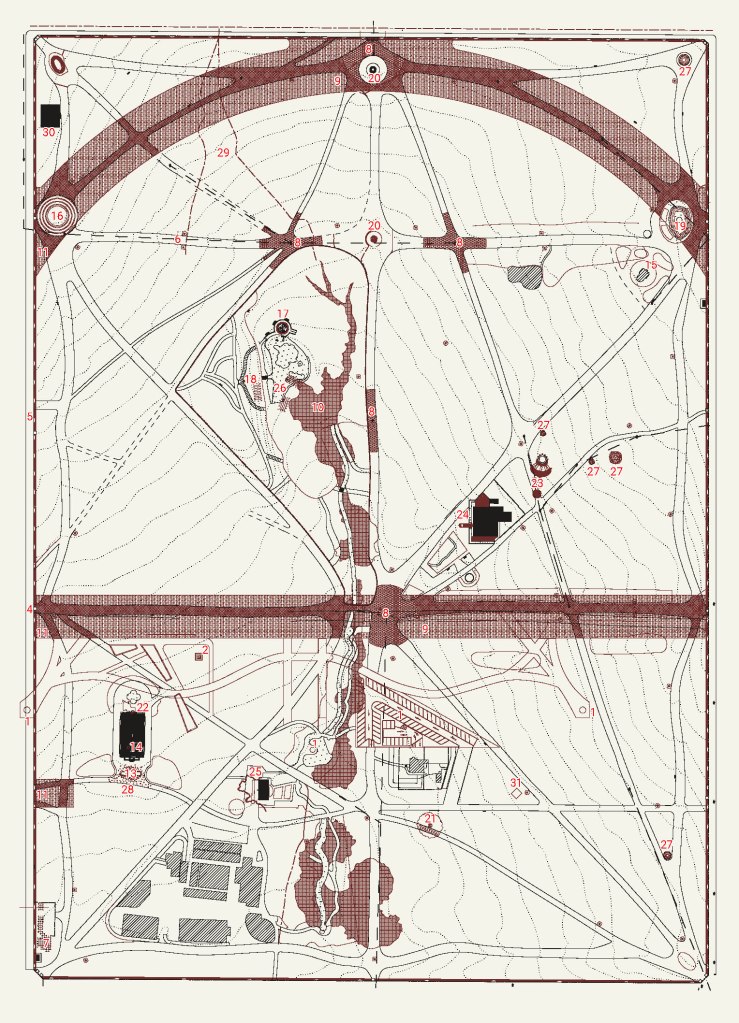

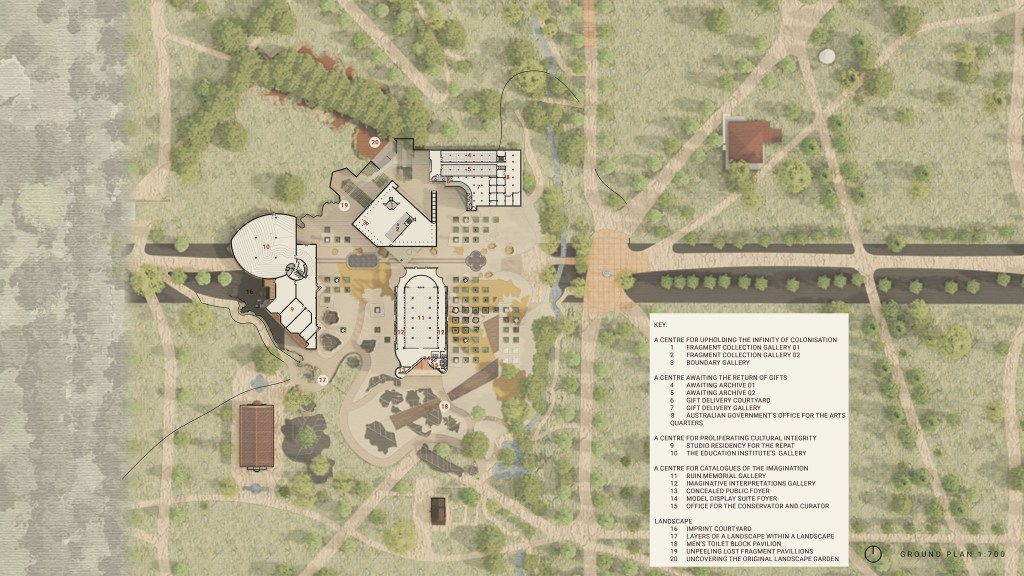

The project involved creating a collection of buildings within an existing garden, designed to await the return of objects that have been collected, stolen, forgotten, doubted, or misunderstood. The approach to curating these objects begins by situating them within a context where they will not be restored to their original place or purpose. Each building and its program were conceived by evaluating specific object narratives through architectural form, their relationship to the surrounding landscape, and their placement within the garden.

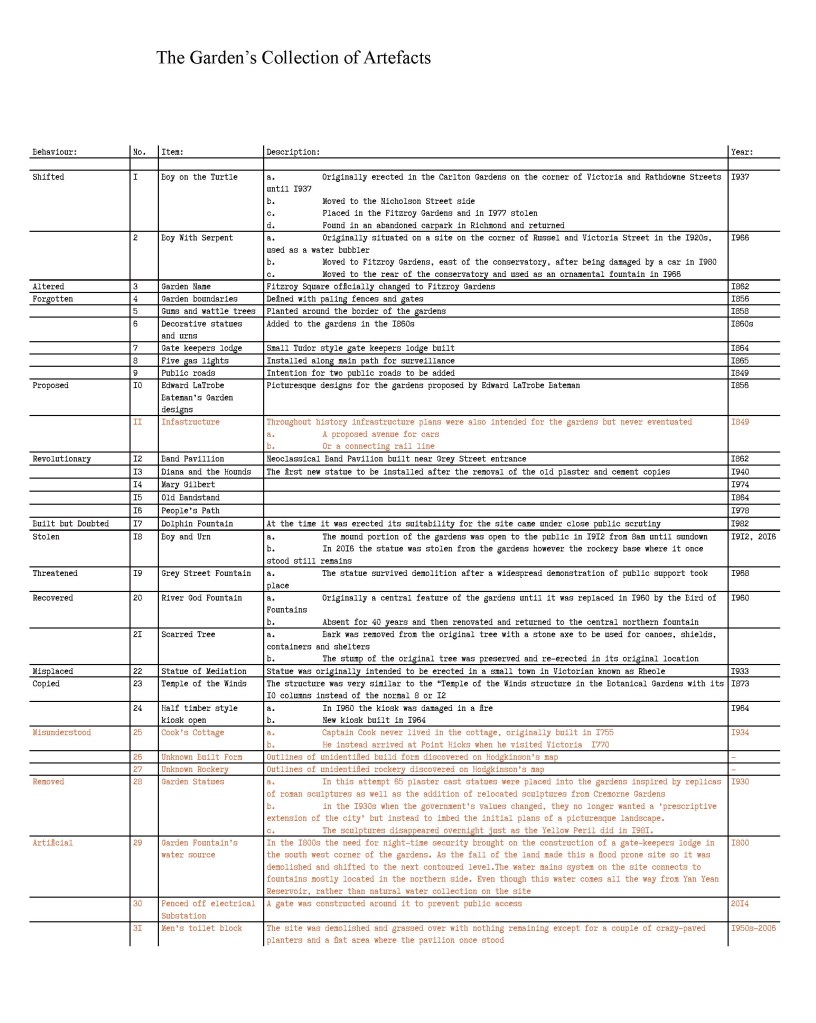

THE GARDEN AND LANDSCAPE

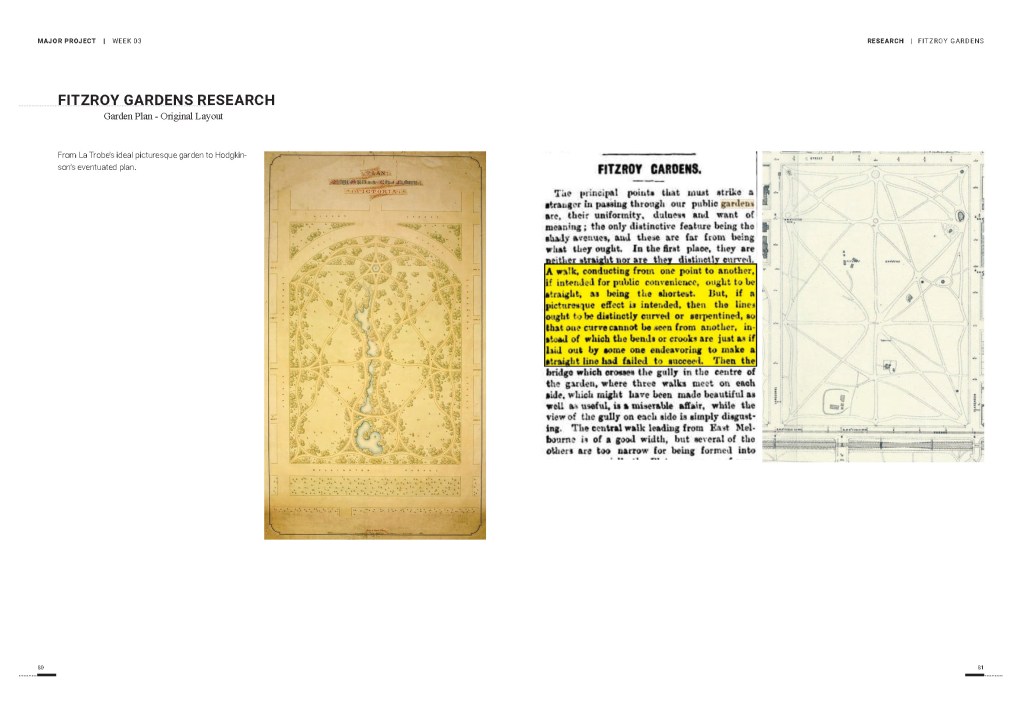

Fitzroy Gardens was selected as a platform for this project to grapple with the impossible list of artefacts and objects that may never return home. The garden is marked by its own mislaid artefacts: a home from elsewhere, the memory of plaster replicas, infrastructure that was never realised, and the Indigenous landscape that once existed. Thus, the garden is both home to and implicated in the problem of repatriation and restoration.

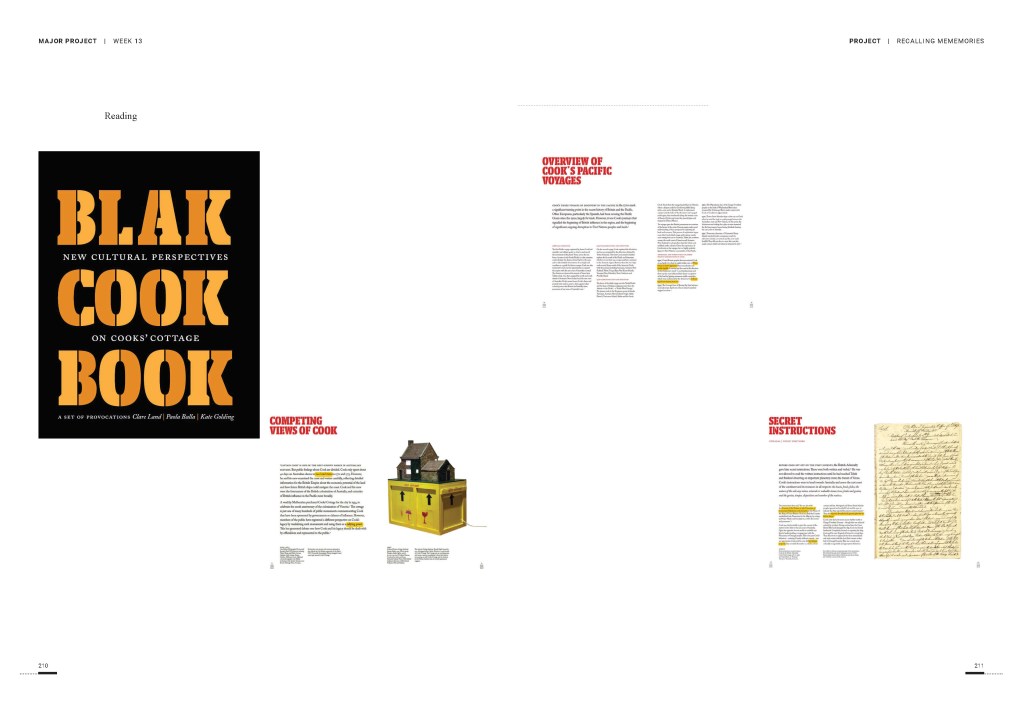

An example of this is Cook’s Cottage. Built but never used, it was dismantled brick-by-brick and relocated by a wealthy Melburnian to represent the colonisation of Victoria. The cottage illustrates a multitude of misinterpretations of history. Its difficult narrative can be explored and showcased by addressing these complexities rather than its current cosy, homely appearance. The building symbolises the myths and oversimplified, one-sided accounts of history that it imparts to its visitors. However, what if this public landmark signified a more nuanced account of history? Revealing a more truthful narrative could involve acknowledging that Captain Cook never actually landed in Melbourne but rather at a place in East Gippsland known as Hick’s Point.

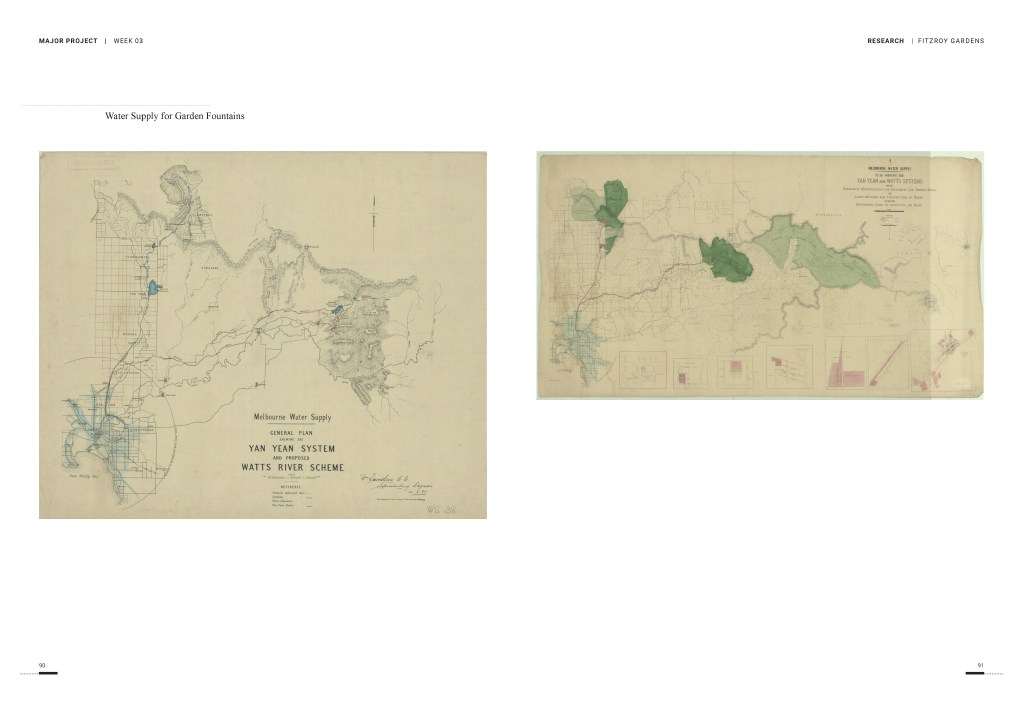

An attempt was also made to recover a landscape through the overlaying of phantom landscapes: the original bluestone ballast that forms Melbourne rising through the sandy ground, surrounded by both manicured and naturally growing grass, and the recovered fragments of carparks drawn to the site by a lost sculpture. Further landscapes retreat or peel away, revealing an impossible terrain underneath. A decisive east-west axis describes the proposed infrastructure that was never realised. The picturesque makes itself known.

THE CENTRES

Particular moments of the list are highlighted through a series of Centres each upholding a function that frames the narrative of the artefacts and objects that cannot be repatriated.

1. Centre for Upholding the Infinity of Colonisation

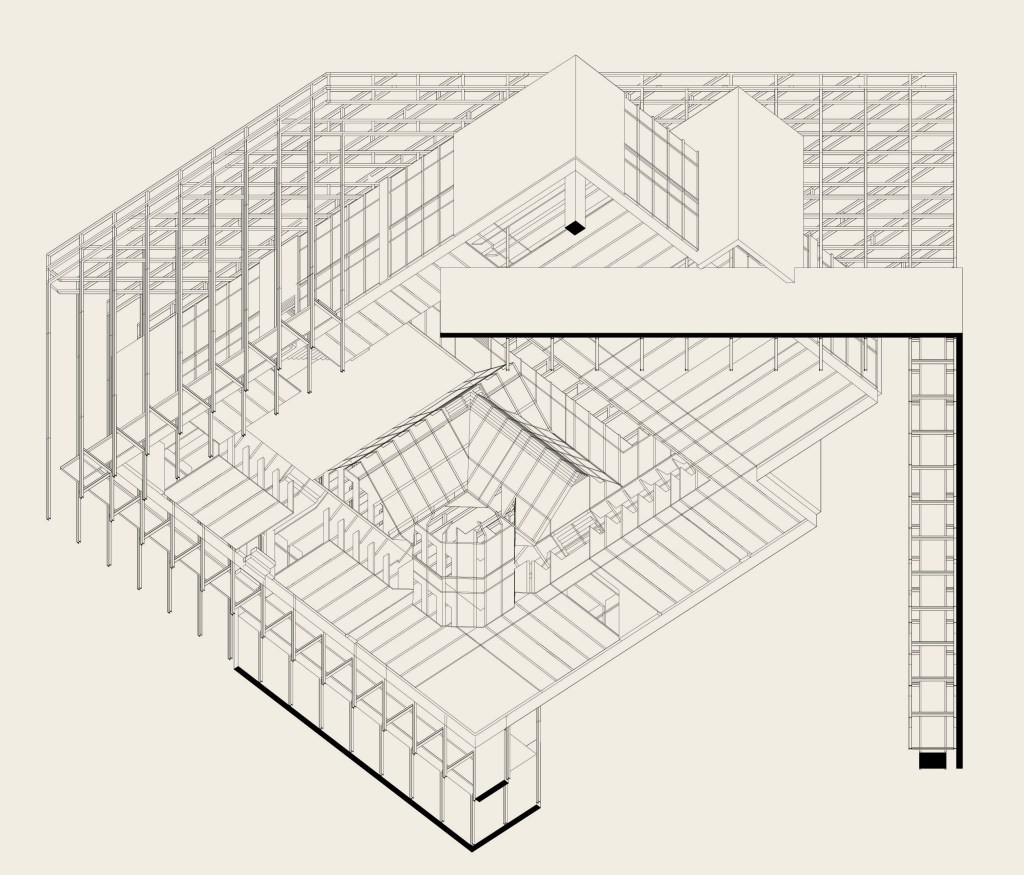

The first building is a Centre for Upholding the Infinity of Colonisation, which brings together collective narratives of cultural property. The building is defined by the absence of its predecessor—the original garden kiosk that burned down—and the presence of the new kiosk. It curates a phenomenological experience to reflect the challenge of reconciling these two states. The original garden kiosk is represented through an absent relief that influences the interior design of the building, creating spatial voids that disrupt the order of categorised shelving.

The interior features shelving that exposes objects—often hidden within the confines of specific categories—to all other objects in the space. These voids allow for a comparative reading of objects across the spatial arrangements of the archive.

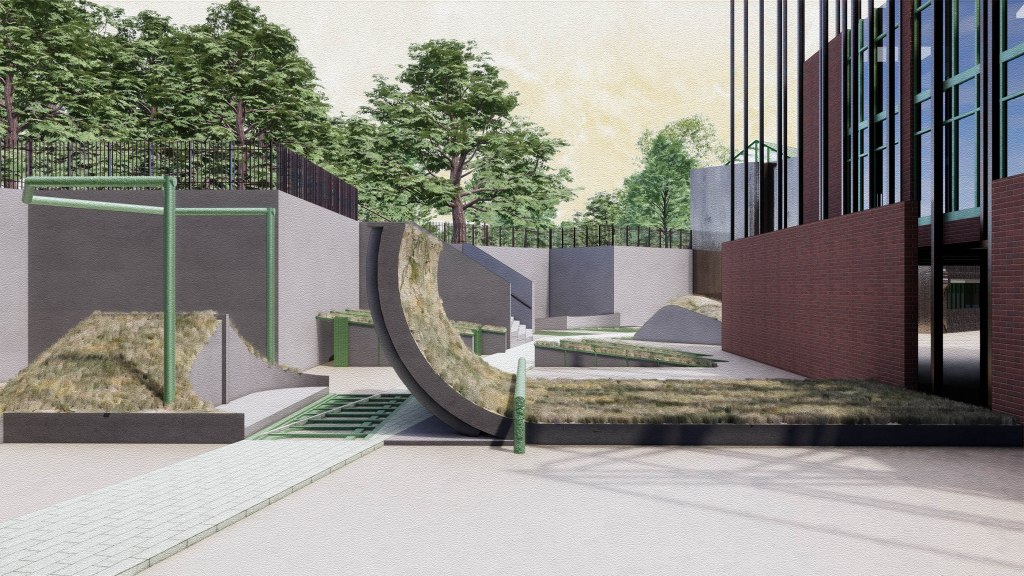

Surrounding the building is a landscape that attempts to recover the original garden kiosk. The landscape recalls key features of the kiosk’s façade, imagining them as fossils embedded in the ground. The archaeological façade extends from the building and interacts with the existing garden landscape, suggesting a desire to confront the potential of an ever-expanding collection of artefacts.

2. Centre for Proliferating Cultural Integrity

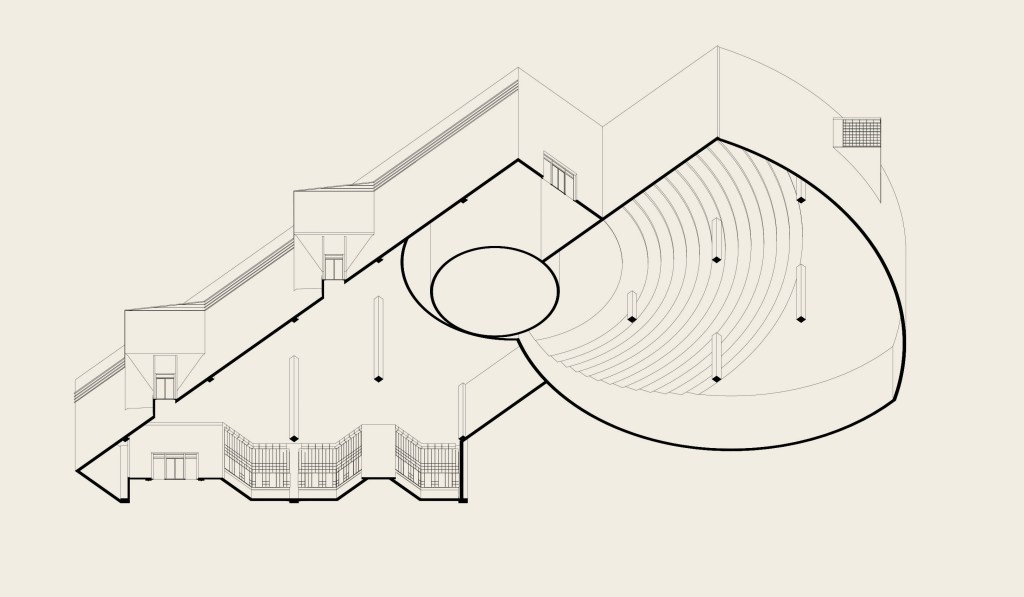

The second building is a Centre for Proliferating Cultural Integrity, a collaboration with educational institutions focused on the temporal aspects of culture and the conservation of materials that embody cultural integrity. The building incorporates elements from the original Cook’s Cottage, replicating its proportions in plan. At a crucial moment, the cottage is dramatically revealed as if viewed through a Claude Glass.

The institution maintains its relevance by offering temporary residency, providing a satirical reflection on the narrative of Cook’s Cottage, which was picked up, transported, and relocated with no ties to a specific place or orientation.

The landscape seeks to recover this narrative by leaving an imprint of the original cottage, tipped onto its side and bordered by an outline of the coastline Cook was known to have landed on, carved into the garden landscape. The garden path forces visitors to engage with both the imprint and the original cottage. As the carved border meanders through the landscape, it directs the viewer’s gaze back to the distant original cottage.

3. Centre for Catalogues of the Imagination

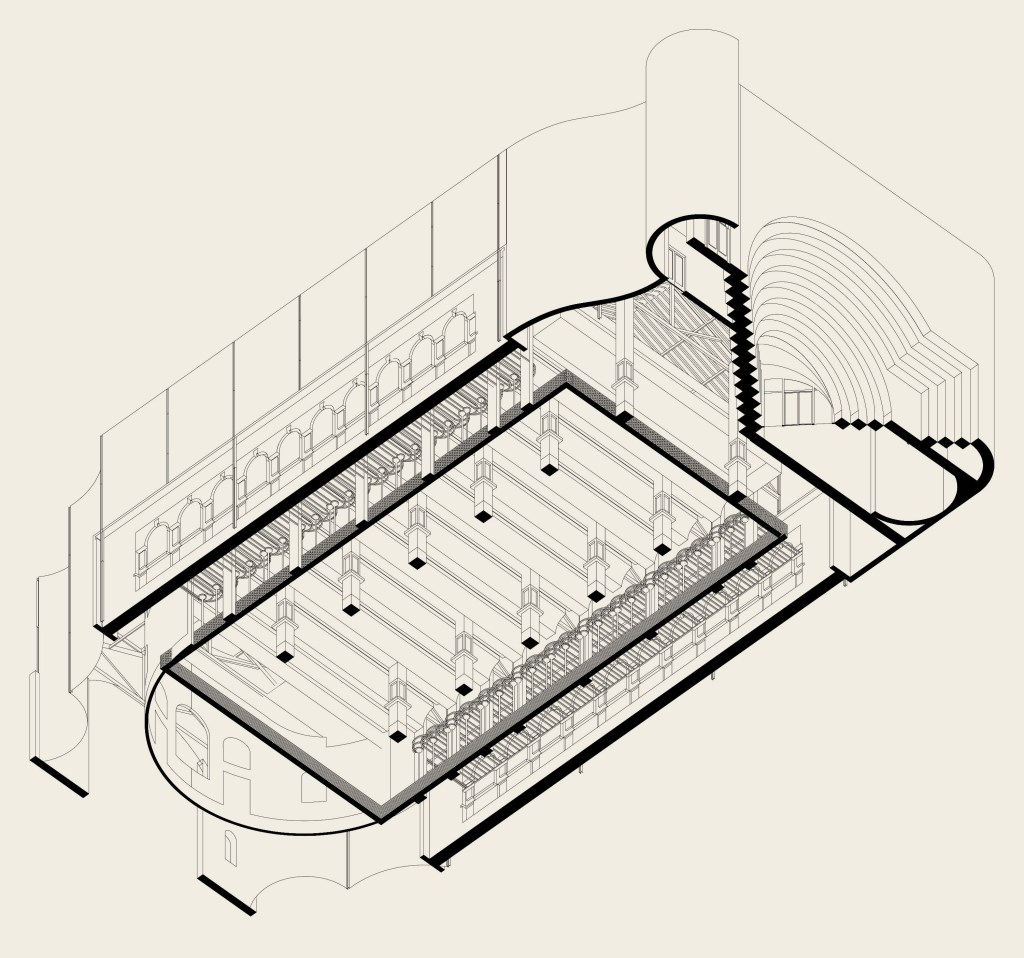

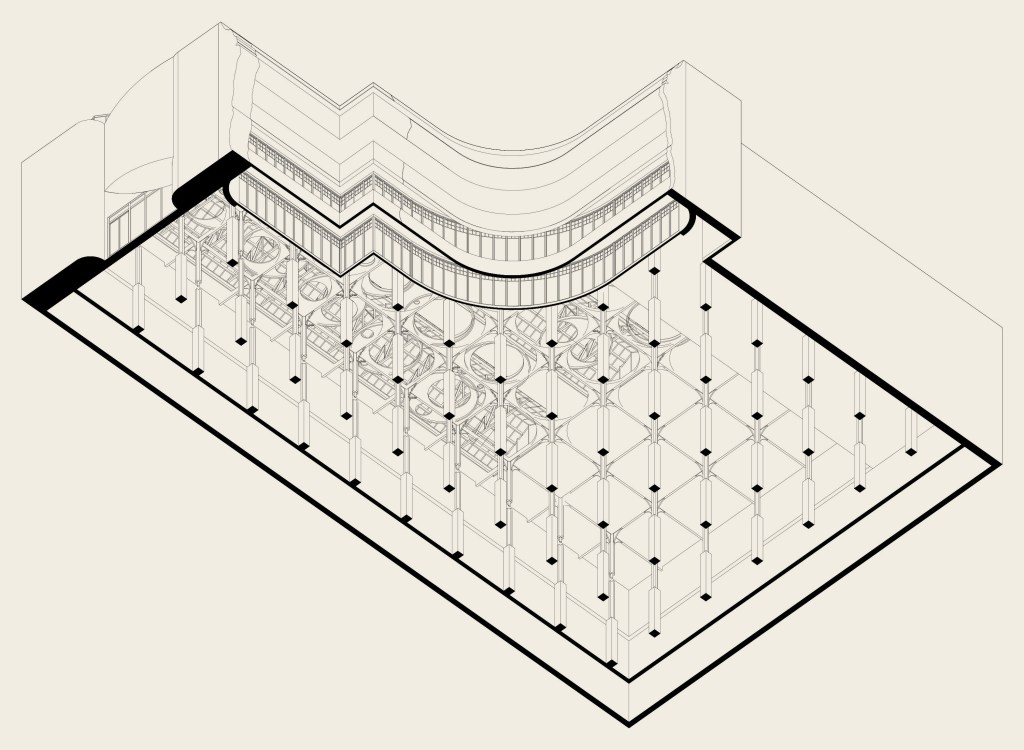

The third building is the Centre for Catalogues of the Imagination, designed as a repository for what will inevitably remain incomplete collections.

The building reflects the Moorish-style conservatory that once occupied this corner of the garden. An imprint of its original fan staircase is folded into the façade, creating a grand but blind public entrance. The final steps lead to a replica model of the original conservatory, concealing the intended private entrance for the conservator and curator. Concealed around a corner is a shear wall with an imprint of the original doors, allowing access to the public entrance behind it.

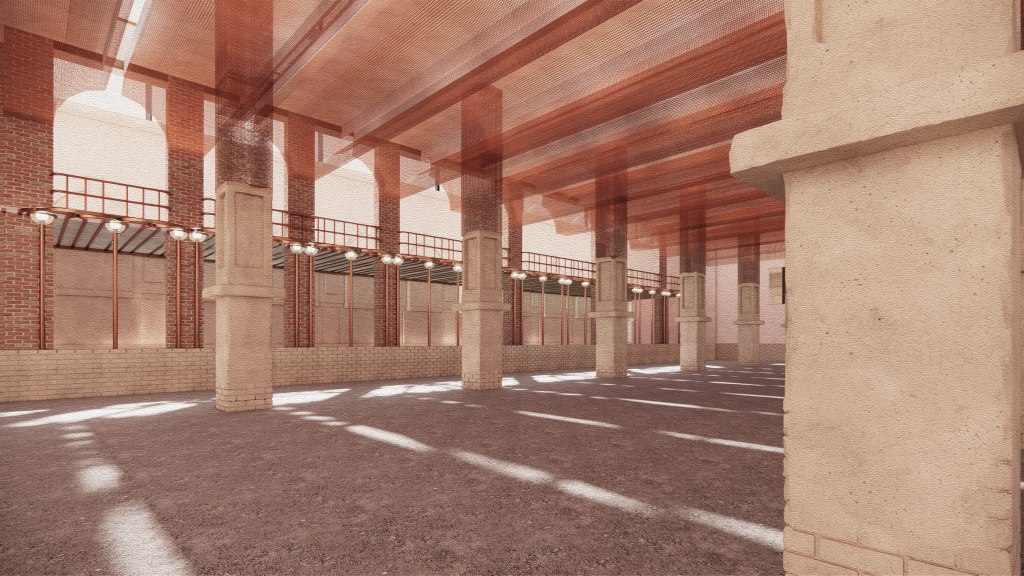

On the ground level, the public engages with the implied ruins of the original conservatory. On the upper gallery, the conservator preserves any building fragments within a mesh encasement. This work is overseen by the gallery curator, who occupies the topmost level and manages the categorisation of the collections. The walls enclosing the gallery document the original conservatory’s elevation in relief, and continue as imaginative interpretations to form the balustrade.

Future expansion is suggested by the continuation of the building’s columns beyond its exterior walls. Across an expanded landscape, the intersecting lines of the construction grid recover a piece of the indigenous landscape, while others return garden plinths that once held plaster statues. Some elements suggest a column as the first step toward the proposed building expansion.

4. Centre Awaiting the Return of Gifts

The fourth building is the Centre Awaiting the Return of Gifts, operating in collaboration with the Australian Government’s Office for the Arts ‘Cultural Gifts Program’, which offers tax incentives to encourage people to donate cultural items and return them to Australian public collections.

The building reflects on past wrongs through an expanded silhouette of the Indigenous scarred tree in the garden. Repeated references to the original conservator’s cottage are made in the window treatments. The interiors capture the qualities of the original tree canopy through voids and cut-out ornamentation. The building fosters public engagement through its courtyard.

CONCLUSION

The project does not resolve the repatriation of objects but explores how the difficulty of repatriation and restoration can be expressed through architecture. This project was inspired by my journey back to the tiny island of Vis, having grown up in Australia and learning about its culture through the stories of my grandmother, who lived there over half a century ago. In her words, I found myself not entirely Croatian or Australian, but rather identifying with a place that exists somewhere in between. The project is an attempt to preserve this sense of “elsewhere.”.