Artem Promovemus Una | We Advance the Art Together

RMIT University Master of Architecture Graduate Project 2021

Supervisor: Michael Spooner

This project looks at the franchise model of Domino’s Pizza and applies it to the Australian Institute of Architects. It was inspired by the founder of Domino’s, who brought together the largest collection of Frank Lloyd Wright artefacts in the Prairie-style franchise headquarters.

A franchise is an opportunity to hold a single identity across multiple sites. The decentralisation of the AIA allows for its charter to be acknowledged by smaller collectives of architects. Within each enclave is held an occasion for debate and conjecture.

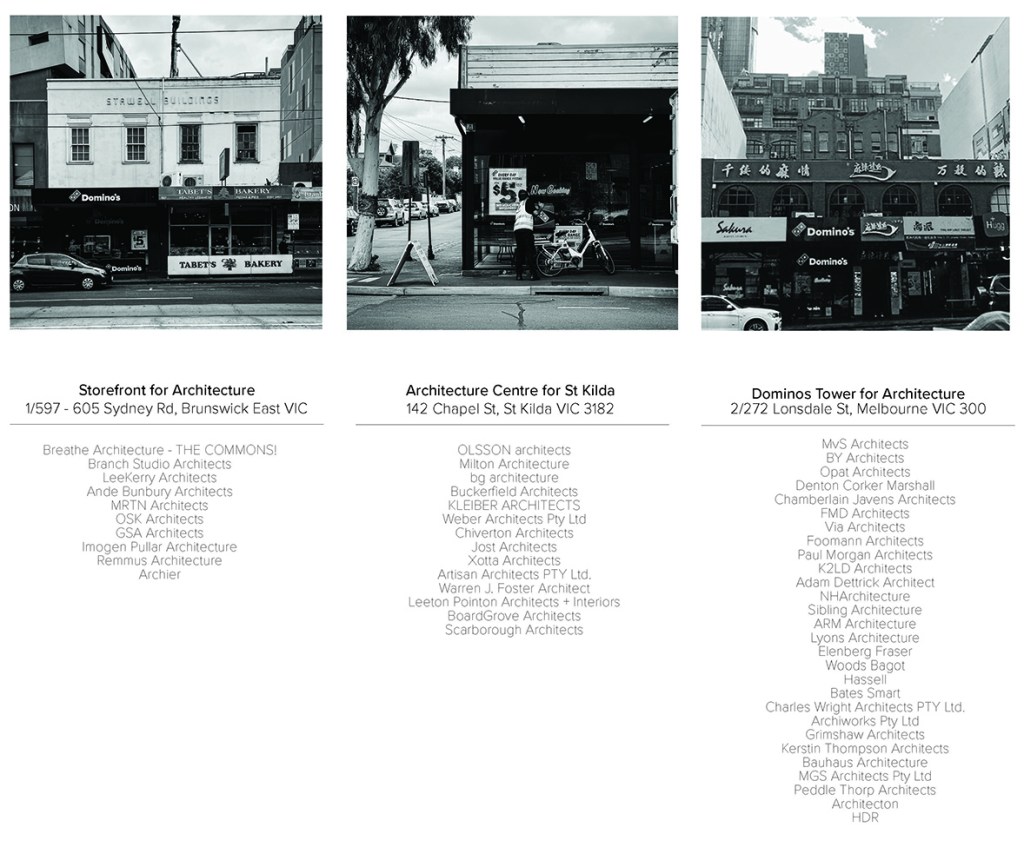

The project spans three sites that were once home to a Domino’s franchise. Each site is an architectural centre specific to the surrounding locale: on the high street, in an inner suburb, and in the city. Together, the three sites reflect the growth of the franchise and attend to the different opportunities to advocate on behalf of the discipline and for those who can invest in it.

PROLOGUE

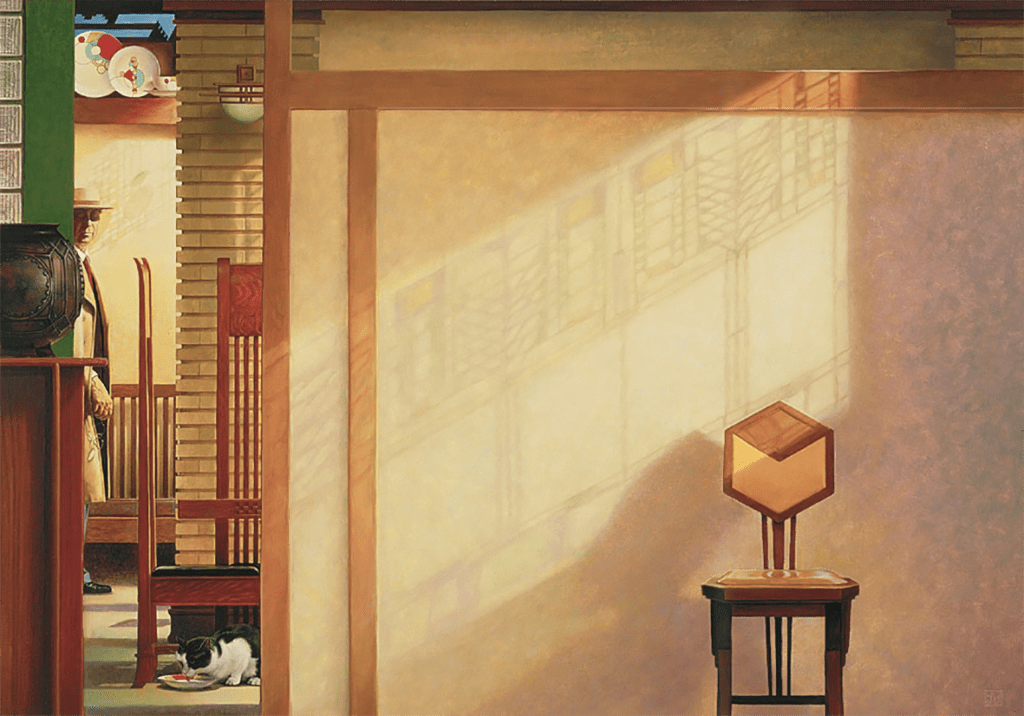

Let me show you a personal framed poster situated in my room labelled Frank Lloyd Wright – preserving architectural heritage. This inspired the entire project.

This poster was in fact in cooperation with the Domino’s Centre for Architecture and Design.

Yes, the Domino’s Pizza Collection, it’s a thing!

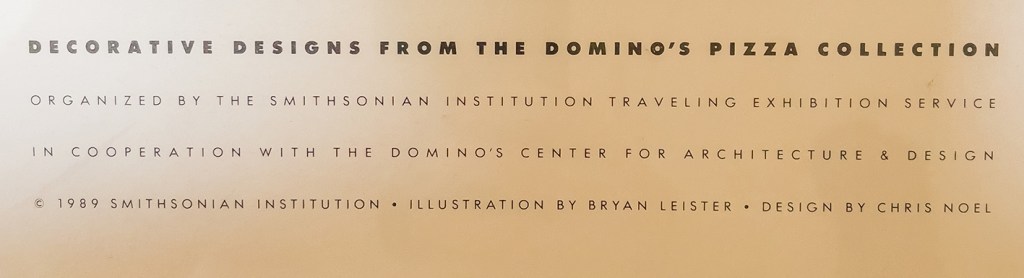

The founder of Domino’s Pizza, Tom Monaghan, beyond a Pizza Empire, had a passion for architecture and greatly admired Mr. Wright and built the largest collection of Wright artefacts in the world. Domino’s Farms is a building that was architecturally designed in the Prairie School style, a style famously associated with Frank Lloyd Wright, by award-winning architect Gunnar Birkerts …a Pizza Empire who strived for the Wright Stuff

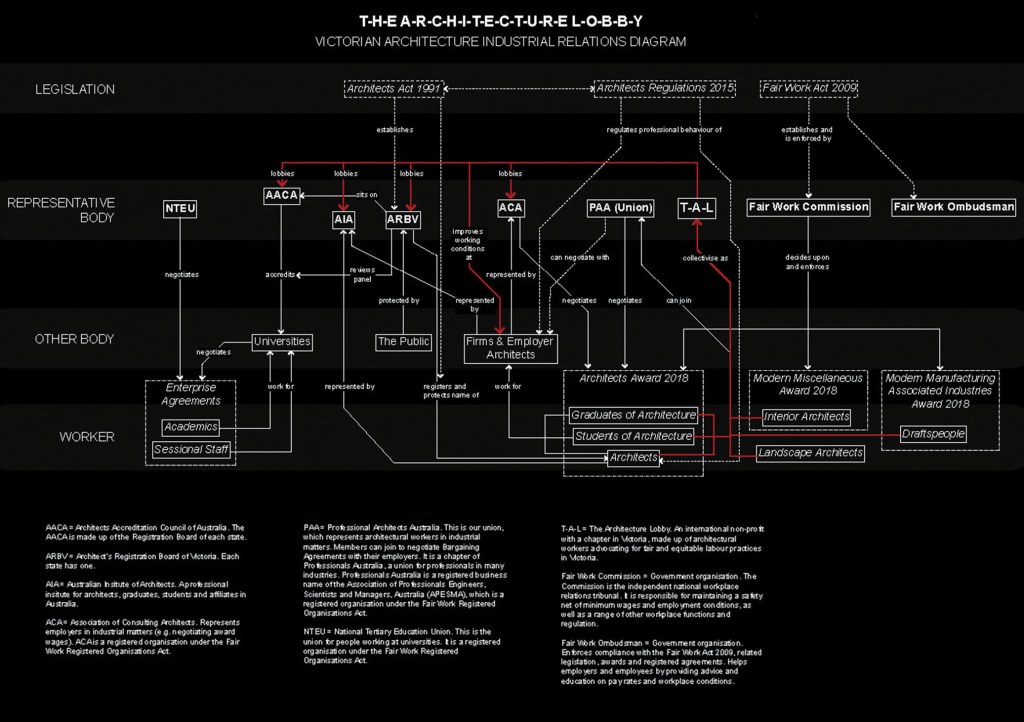

The project positions Domino’s Pizza as a model for the decentralization of the Australian Institute of Architects.

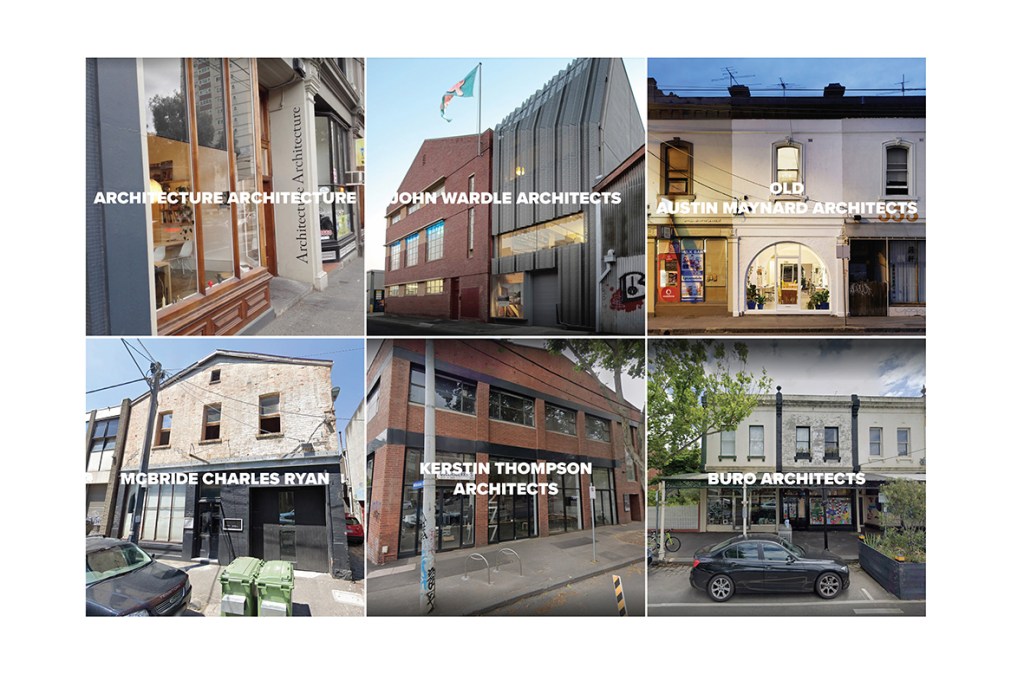

The implication of Domino’s is that the project navigates the fine line between site conditions and the common ecology and language associated with franchises. A franchise provides the opportunity to maintain a single identity across multiple sites. However, each franchise operates independently due to the varying contextual parameters at each location. In some ways, the architecture profession mirrors this, with architecture firms engaging with the public realm either through the deliberate redesign of their buildings (such as Kerstin Thompson and John Wardle) or by opportunistically inhabiting former storefronts (like Buro, Austin Maynard, and Architecture Architecture).

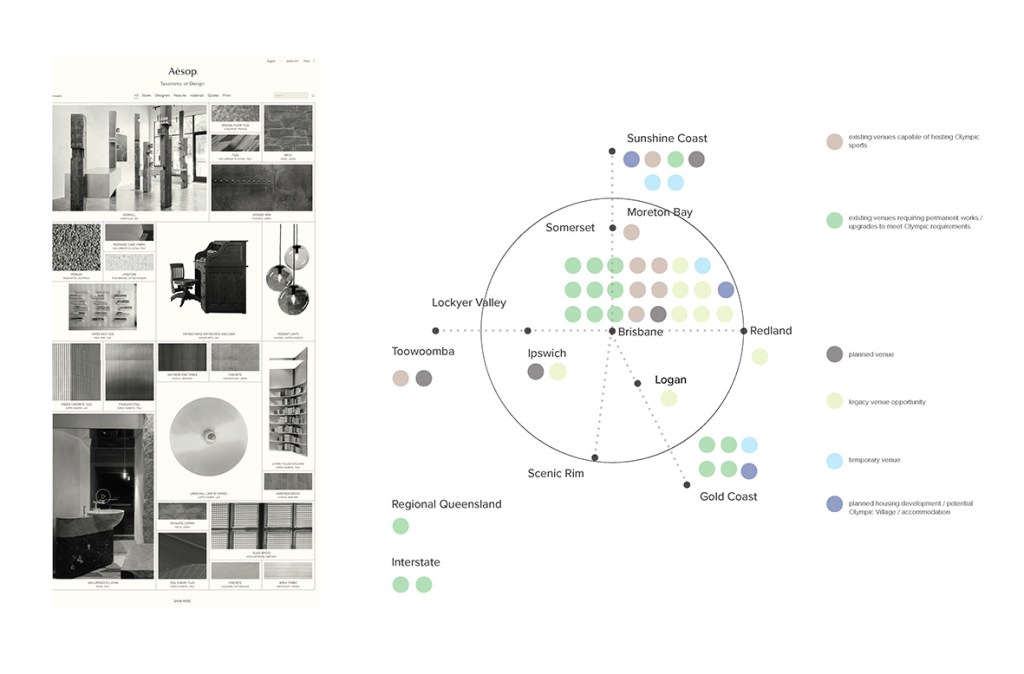

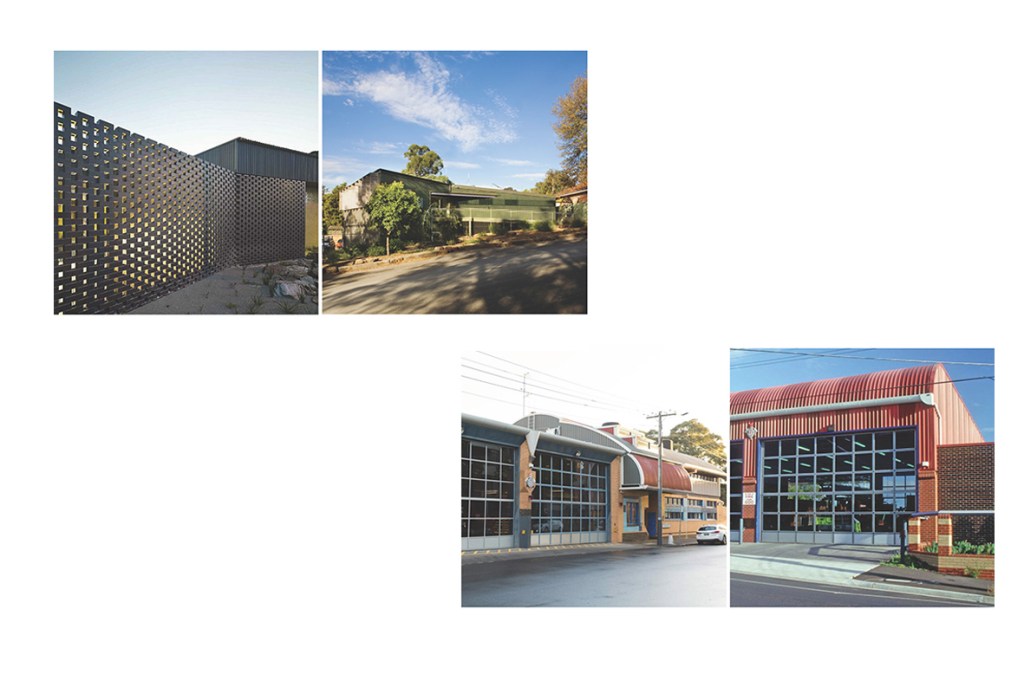

Other models were investigated that reflect the framework of a franchise without necessarily being one. The cosmetic brand Aesop achieves profound specificity in each store but maintains a ‘taxonomy of design’ through shared features or materials—similar to how pizza with three toppings offers both limited and generic options. The 2032 Queensland Olympic bid exemplifies a decentralised model within a complex organisation, as every aspect of the event is distributed across the state rather than being confined to the city. Childcare centres, though a legislated service, were accommodated in a variety of existing building typologies (such as houses, warehouses, and corner shops) or new constructions that echo familiar typologies. Examples of architects creating a network of a specific typology across multiple sites, while attending to each building’s architectural character and its relation to the network, include Kerstin Thompson’s police stations and Edmond and Corrigan’s fire stations. The provision of amenities (albeit a bleak example) is mirrored in the multiple PSO pods at train stations across Melbourne, which have been satirically rebranded with new signage as Architecture Centres.

The Project

The project spans three sites, each once home to a Domino’s franchise. Each site is repurposed into an architectural centre that reflects the character of its respective location: a high street, an inner suburb, and the city. The decentralisation of the AIA allows its lease to be managed by smaller collectives of architects. Each enclave provides an opportunity for debate and conjecture

SITE 1: 605 Sydney Road, Brunswick East

What happens if the building itself is a shopfront for the presentation of architecture? The tenacity of the first franchise is held in the concern for the object: an architecture gallery situated in the bigger urban fabric of Brunswick. The concept of a shopfront of architecture on the high street serves as an instrumental diagram for advocacy and the profession, made to be seen. It offers an opportunity to gather, an ‘opening of doors’ to the collective, and a performative and playful exhibit inviting people in to ‘take away’.

Holding a passive relationship to what is displayed and a more obvious and tangible presence of the AIA, the project explores the idea that architecture is a service associated with the exploration of the city. This creates a totally different condition when closed. The form, as a result, is amplified within its congested context and points to something centred around pure iconography.

When opened, it’s a consideration of space not only for the object but also as a small forum for industry participants, a night event showing the idea as more definitive with activities happening consequently. Day or night, opened or closed.

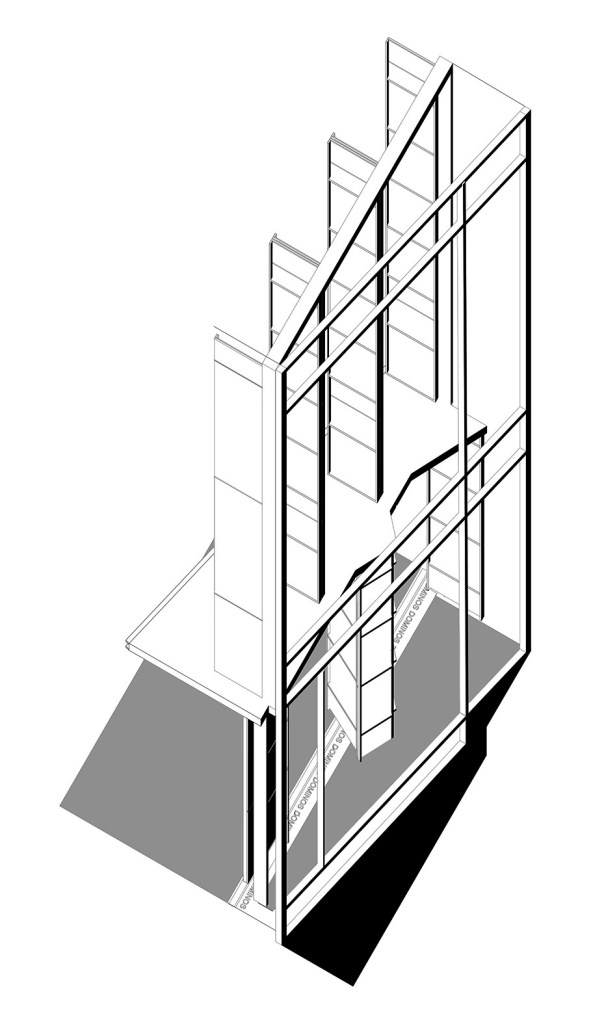

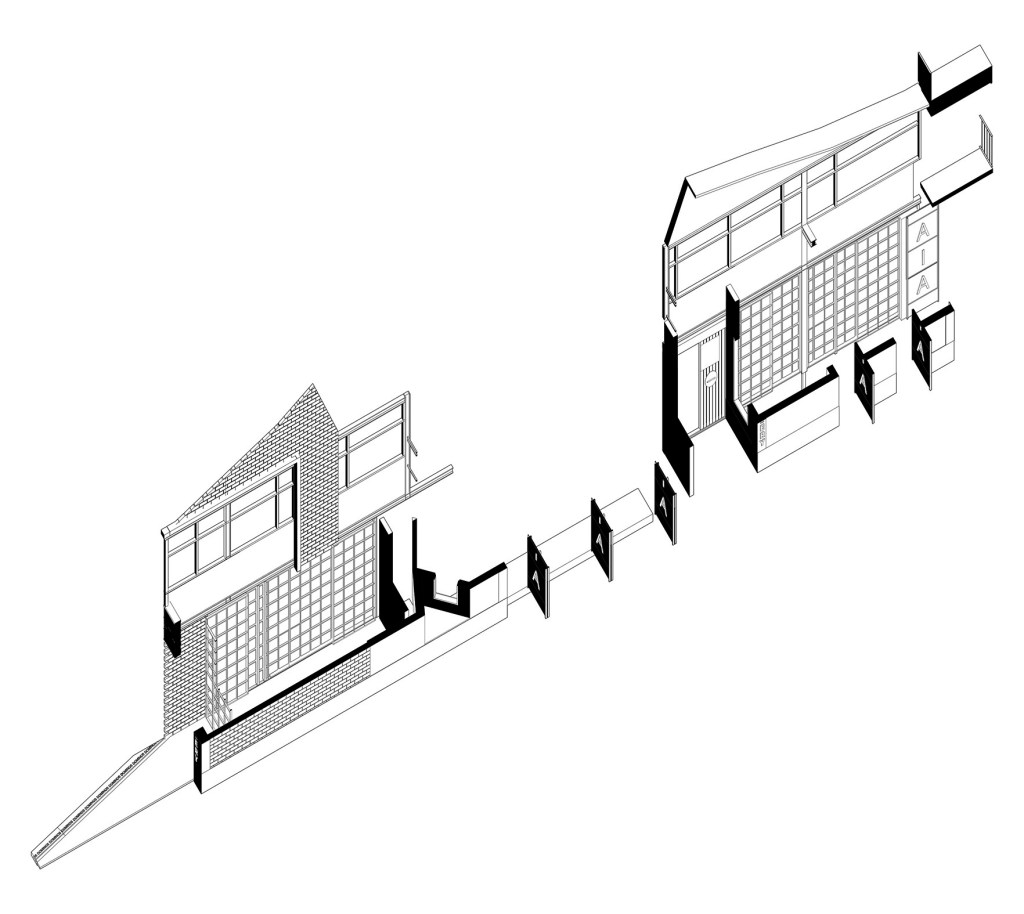

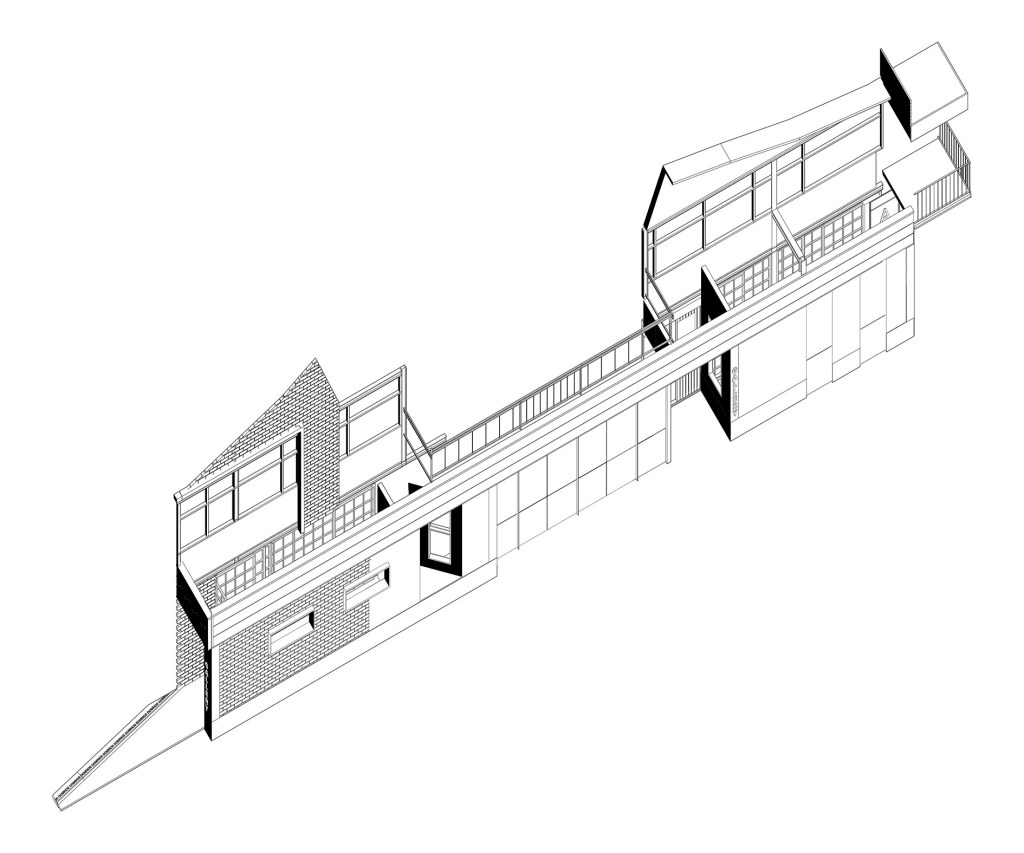

It’s a plug-in interface along Sydney Road, designed with sensitivity to coexist with the memory of the existing structure rather than replace it.

The original signage ‘STAWELL’ and window façade are pushed back 2.5 metres to the existing apartment balcony above. This axonometric section shows how the architecture sits where the front condition is where the design is held, while the back supports the performative frontage of the building in a functional sense, defined by a generic kitchenette and storage. The materiality and design consider the possibility for the front condition to adapt and change depending on the enclave of architects.

The accessibility is ensured by its front and street orientation, reflecting back to Domino’s and its inherent accessibility as a street condition. The architecture makes the difference, working hard as a series of conditions in the first few metres.

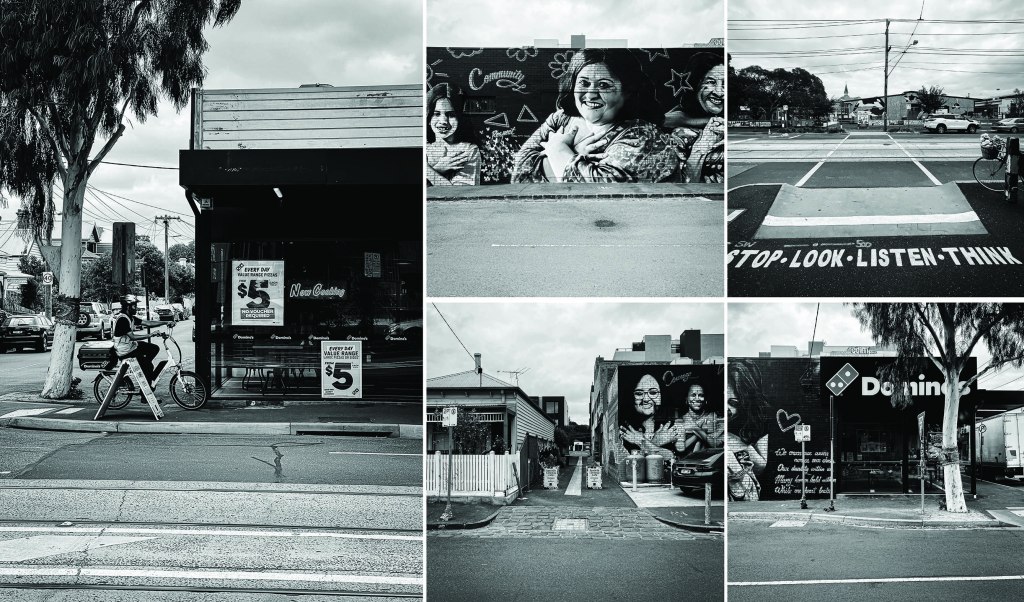

SITE 2: 142 Chapel St, St Kilda.

There was a point in my project that attempted to view the franchise model in the territory already occupied by architects. The Robin Boyd-designed Neptune Fishbowl ‘Fish n Chip’ shop, at first glance hyper-specific and expressive, was supposed to be expanded as a franchise, with the formal device of the blue sphere replicated at 10 or more sites. There was also the contribution of other architectural advocates, particularly the Boyd Foundation headquartered in the Robin Boyd-designed Walsh Street House. Boyd was a constant advocate for his profession, serving as an architect, public figure, writer, and commentator, and the first director of the RVIA Small Homes Service that sought to popularise the modern home and make it available to a broad public.

A question of what this project could reveal had been raised early with the Walsh Street House imposed across the site with surprising ease. How much architecture was needed for the franchise to be legible?

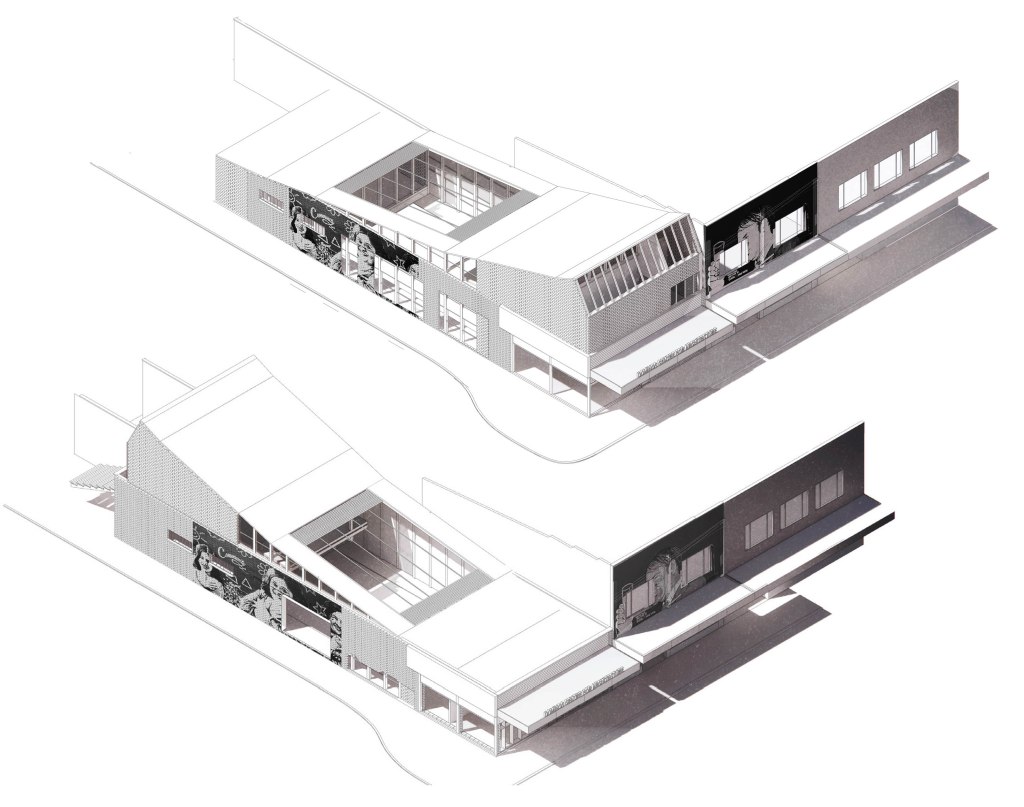

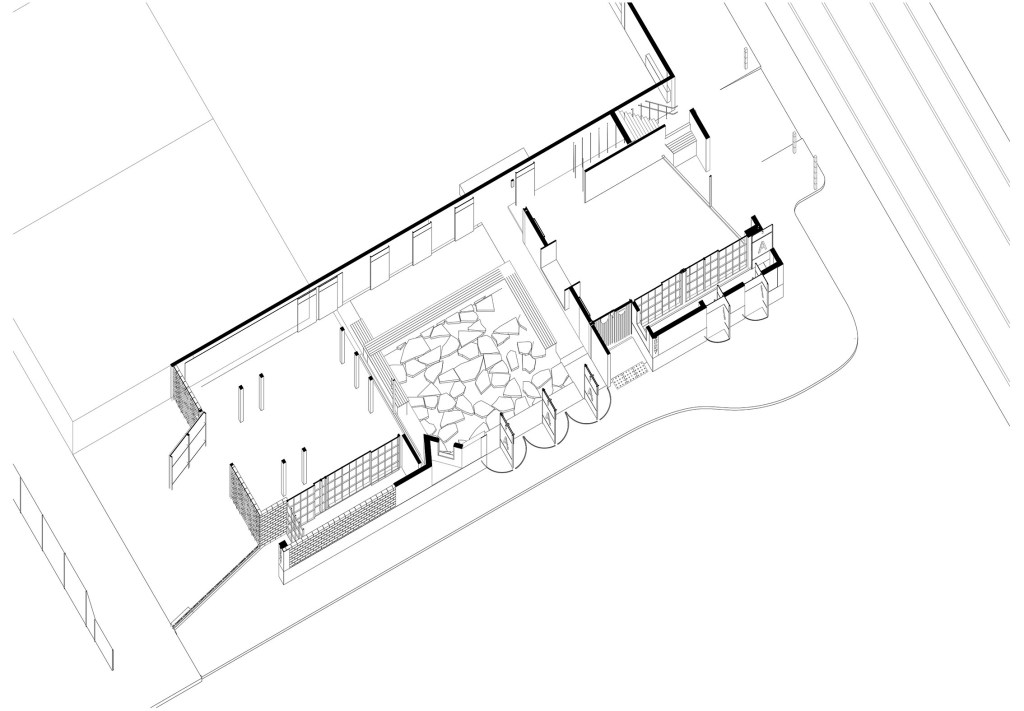

The project took the stance that Site 2 would be the result of learning from the first franchise site in Brunswick East, with consideration of how the franchise is situated within the community and beyond the basis of broad architectural advocacy. The proposal becomes a space shared with the community and the contextual adjacencies, including a school. This space reflects the eat-in Domino’s, which was present before. People are not only invited in but also welcome to stay.

The Centre façade reflects similar characteristics of the Brunswick East franchise. It attempts to architecturally situate itself across the existing architectural features, requiring the proposal to do a lot in the first few metres. When you cut the existing façade away, the architecture sits delicately behind, and a series of small interfaces and spaces between the street and the new centre are revealed, with no definitive entrance.

The centre is oriented not only to the street but also holds a central garden that serves as a platform for events and the focal point for the galleries that open into it, and an area for contemplation from the office spaces above. The two galleries present different opportunities to frame the consideration of their contents. One is framed towards the street, while the other extends from the current art lane.

The Centre modestly frames a forum for community engagement.

SITE 3: 272 Lonsdale Street, Melbourne CBD

The procurement of a tower in the CBD illustrates the success of the franchise and was an attempt to evaluate a more robust architectural outcome. It required the franchise to have a broader vision than the previous sites. This harks back to Domino’s, where certain franchises are given more money to begin with, each operating independently, with performance dependent on the economy around it. The tower, the next step in the evolution and presence of the two prior sites combined, serves as a public interface that highlights its city location.

The project considered an urban billboard as a distinct condition for the presentation of architecture. This was reflected in the oblique positioning of the building against the direction of the city grid and the distended façade that hovers above the street. The thinness in the application of architecture, first seen in the unfolding façade of Site 1 and emulated in the brick-and-mortar façade of Site 2, secures a distinctive narrow layer between window and façade that makes the profession immediately visible to the public.

The streetscape and ground condition are expanded with a small urban courtyard. The existing entry stair informs an intimate interior condition, enabling passage to the neighbouring Chinese restaurant and the emerging architects’ offices.

From the laneway, a glazed opening in the bluestone cobbles enables views into the gallery below. The laneway is given new life as a public thoroughfare and informal gallery forum, a far cry from its prior existence as the ugly side of backhouse Domino’s or that 5 am exit from Baroque nightclub after a big night out.

Alongside the existing CBD towers of other professions and industries, the proposal is symbolic of the architecture community validating the franchise. There’s some truth to the idea that good buildings are billboards for architecture. Most people don’t engage architects, but everyone engages architecture. This building is evidence of what we can do as architects.

CONCLUSION

The project was held to a single ambition: positioning a community of practitioners around a particular building as an instrument and evidence of the profession. While the project recognised the limits of a franchise model, it was an attempt to progress the debate on professional efficacy.

Each site has a specific architectural concern that speaks to the building’s generosity in the service of architecture, by architecture. The three sites examine the growth of the franchise but address the different opportunities to advocate on behalf of the discipline. Interestingly, the procurement framework emerged quickly, but it was during the testing of architectural strategies—an examination of the legibility of the architecture across three very different scales—that I found challenging.

Early in the process, I attempted to have the same complete language and outcome as the first project. I then found success when I pursued each project through an independent response to the site and then ascertained how the overarching strategy worked in a particular way. It was more beneficial to use the framework to assess the outcome.

My project does not solve the problem of a franchise as an exemplar for the architectural profession. It was an attempt to demonstrate how the problem could elevate a forum of design and thus elevate the profile of architects.

There was some truth in allowing smaller collectives of architects to have a slice of the AIA with the occasion for debate and speculation. While everyone seemingly had an opinion of the AIA, my own view was towards greater advocacy, education, and showcase.

But hey, if the pretty picture falls away, maybe I’ll take a page out of Tom Monaghan’s book: I’ll sell it, go back to Canberra, and start my own cult. True story.

*A vehement ultra-conservative Roman-Catholic, Tom Monaghan sold his share of Domino’s and funded Ave Maria Town (est. 2007) in Florida, a religious-centric planned community.