Monkey Wedding

RMIT University Master of Architecture Graduate Project 2023

Supervisor: Michael Spooner

INTRODUCTION

“Monkey wedding” is an idiom for a sun shower.

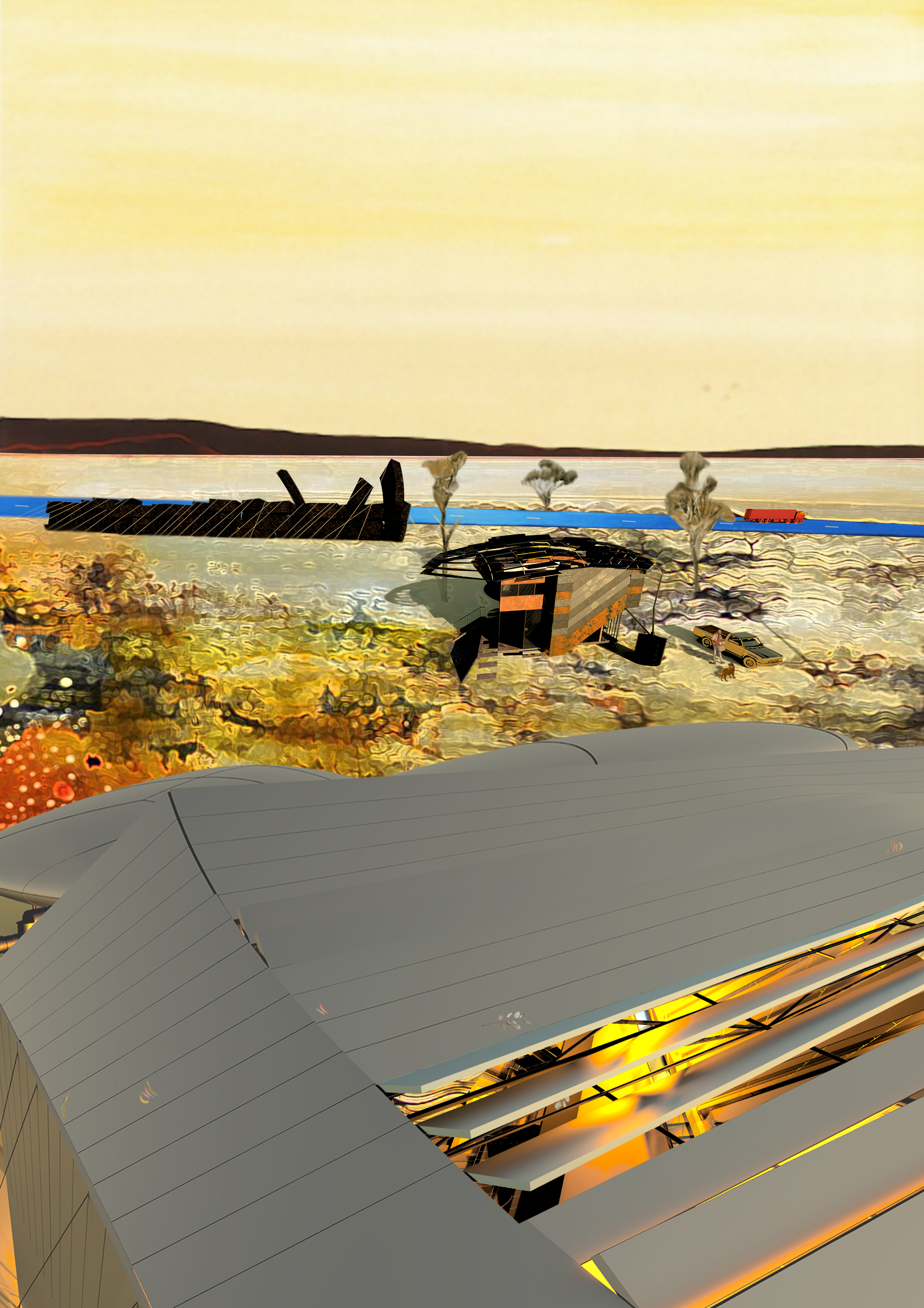

When the sun rises over Parwan, the day begins. The caretaker pores over today’s agenda. The wind is blowing west, the dry grass flutters in a wave, and a sweet smell rides up the blades as condensation drips off the recycled metal cladding into his freshly cracked beer.

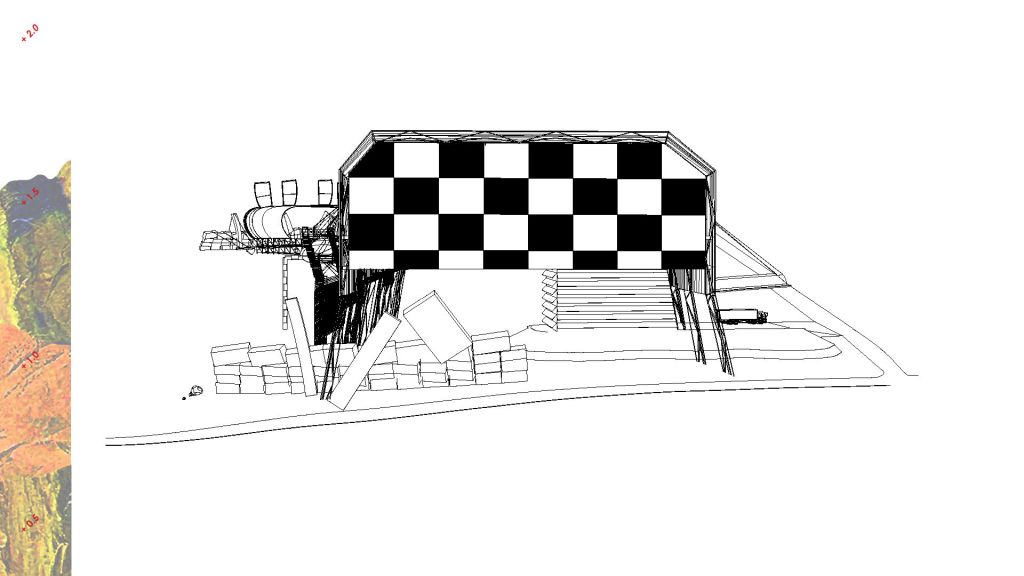

The sweet smell of degrading waste and brown coal combined reminds him of home. The rising sun reflects off the bow roof providing shelter where care is taken. He takes a swig and looks up, catching a fractal reflection of a checkered facade. Flying through the sky, the ex-K9, transformed into a compressed diamond, is chartered toward home.

Another twin-propeller plane passes overhead from Bacchus Marsh Airport. Flight RXA489 glints in the distance without a bird or winged creature in view. The altitude feels greater due to the vast void below. Peering across the plane, haze dissipates into the air from the flues next door. The first morning visitors arrive, descending down the 2-metre trench, bending around, then ascending up the ramp and through the drawn-back opening. One guest seems to be wielding a cow, making one last visit before heading to the final destination at Eden Hills across School Lane.

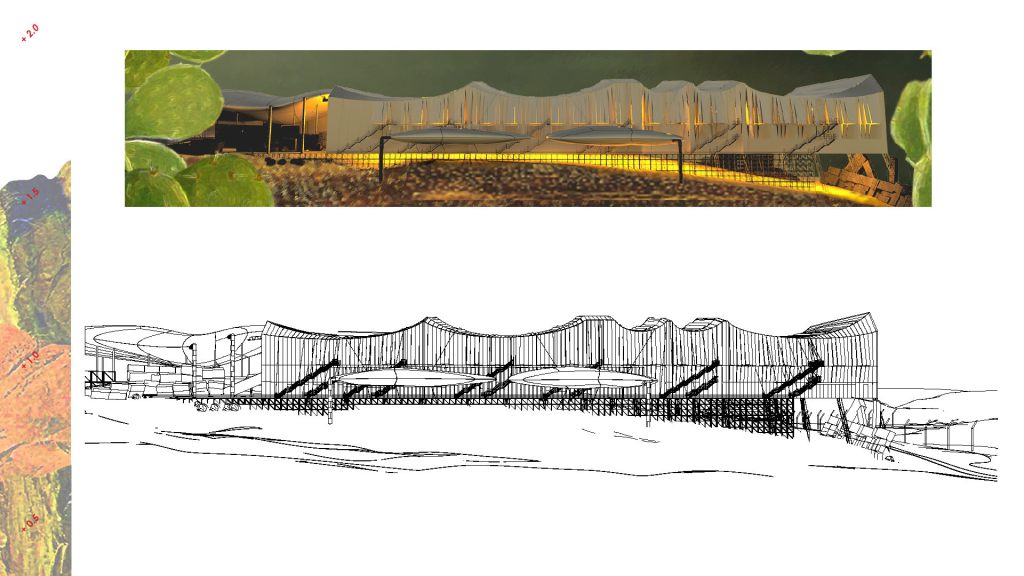

End-of-day floor mopping from last night draws eyes downward while shafts of light travel through the overhanging light well. Peering up to the horizon above, a ravine is tucked down in front. Above, a shed is perched on thin legs and oriented to the west. Looking through seemingly foreign yet somehow familiar flora, the abutting roofs, one inflated, one solid, bend toward the sky, gesturing an opening.

Across the humble hill atop the rocky ravine, the full length of the shed can be seen. Leg by leg, it hovers patiently over the dry ground. The flowing roof resembles something you’d launch a motorbike off. Another Lin Fox rockets past on Bacchus Marsh – Geelong Road, as the trees sway in its wake. Carlton, the caretaker’s dog, looks up at him curiously as sweat runs from his brow. Three jobs down, three to go—after smoko, of course.

Entering from the point of the abutting roofs, a colossal ramp extends downward, providing passage through almost the whole length of the gallery to the western side. Ascending through and past the archival space, where restoration and preservation occur, relics of the past can be viewed, sometimes by horseback. Back out in the beaming sun, the cherubs haven’t stopped working in the monument yard. The extendable tensile shade provides relief as they deliberate and rearrange marble and stone.

Passing beneath the red sun, an A380 casts its shadow down below as it descends back to the earth. At 13,000 metres, the pilot peers into the depths and piles below. At 13,150 metres, the plane passes over the landfill-coal mine, and the landscape expands below. Below the A380 the visitor centre draws its eye toward the gallery and archive, which gaze into the glowing void of the neighbouring landfill. All the while they are looked over by the caretaker who’s had a half dozen cans by now.

The surreal embellishment of these introductory works and atmospheric visualisations demonstrates a way to perceive the contexts, conditions, and nature of the architectural insertions that dwell upon the site, to bring to light some of the absurd and irate findings surrounding this place.

THE SITE

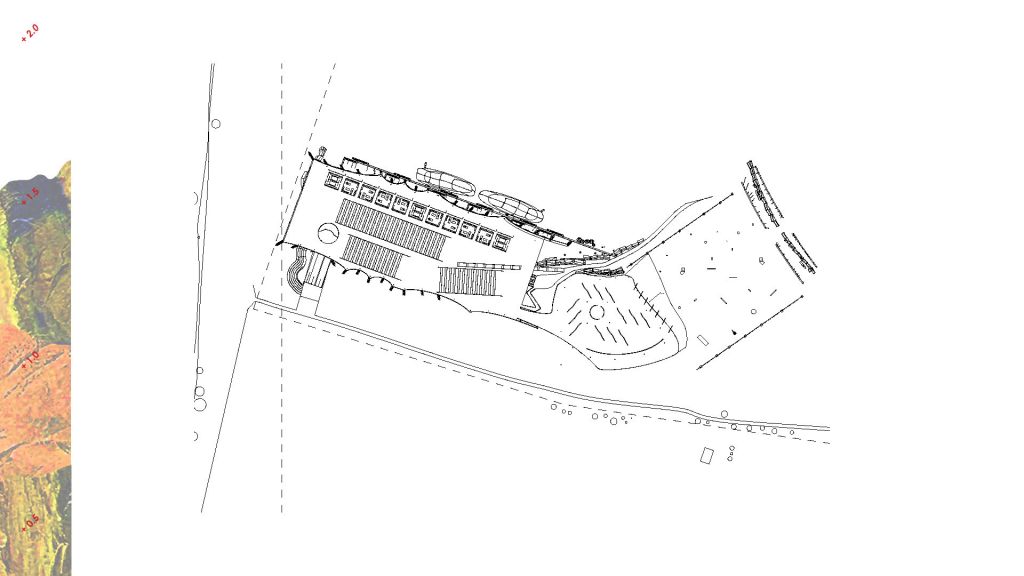

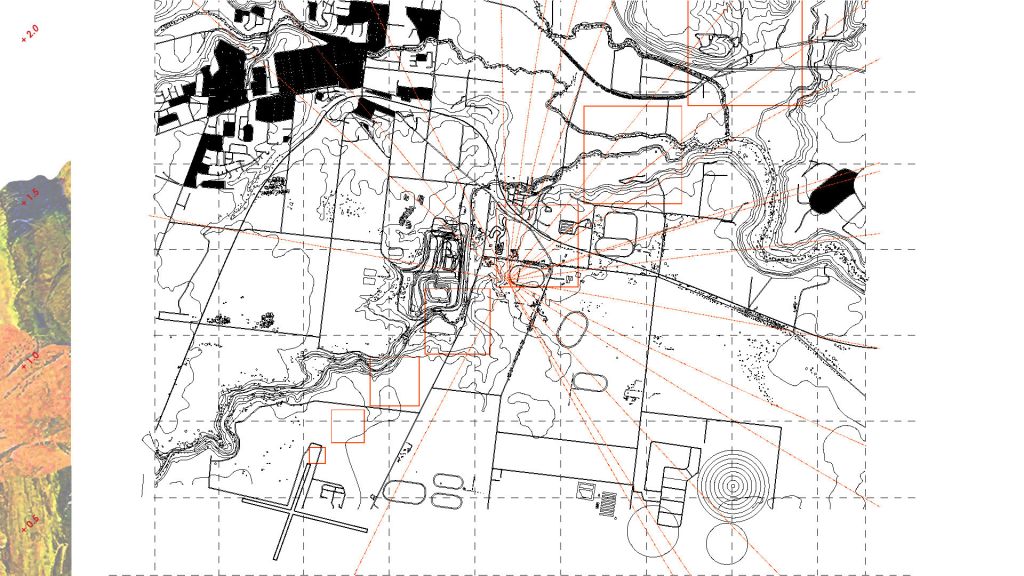

The site at 4265 Bacchus Marsh Road sits on three geological formations: a volcanic basalt plain, alluvium, and the Altona coal seam.

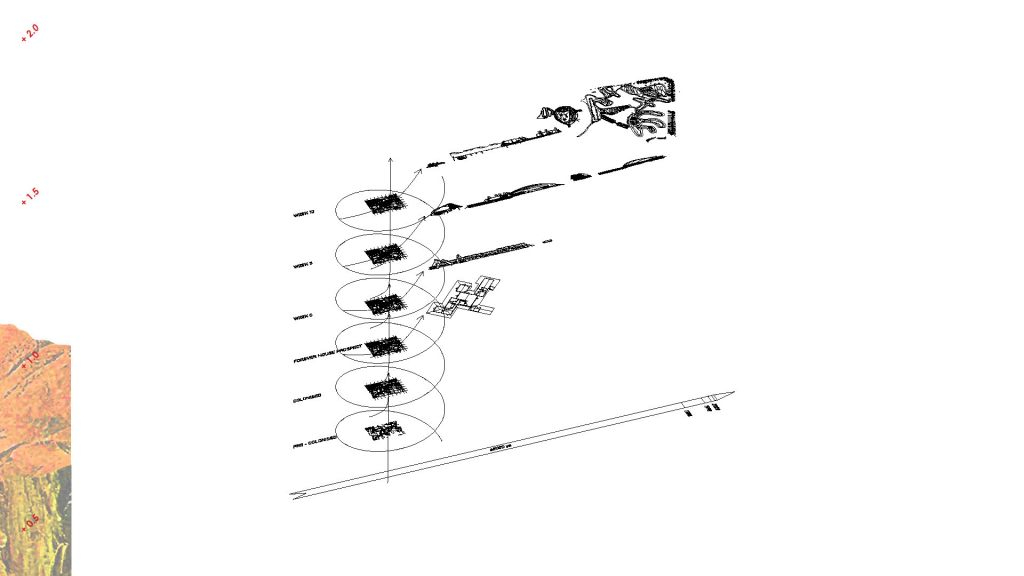

The site is impressed upon and shifted in some way across time, gathering the Indigenous condition, the colonised condition, the unrealised legacy of the ‘Forever House’, the beginning of the thesis project, and the project at Week 5 and Week 10.

Adjacent to the site are the Eden Hills Pet Crematorium, the Parwan Moto-cross Track, and the Maddingley Brown Coal Mine and Landfill.

Intrigued and amazed by the proximity of these three unusual neighbours, their character and forms were considered in analogous architecture that imagined other reflections of them. Precedent and discussion impacted and influenced the shifting conditions that supported their creation.

DESIGN NARRATIVE

A tinnie boat, a rug, a clay handle, and a kitchen sink are all items that might be found in a landfill. Some found elements suggest operative architecture, while others are emblematic of the character of a future occupant.

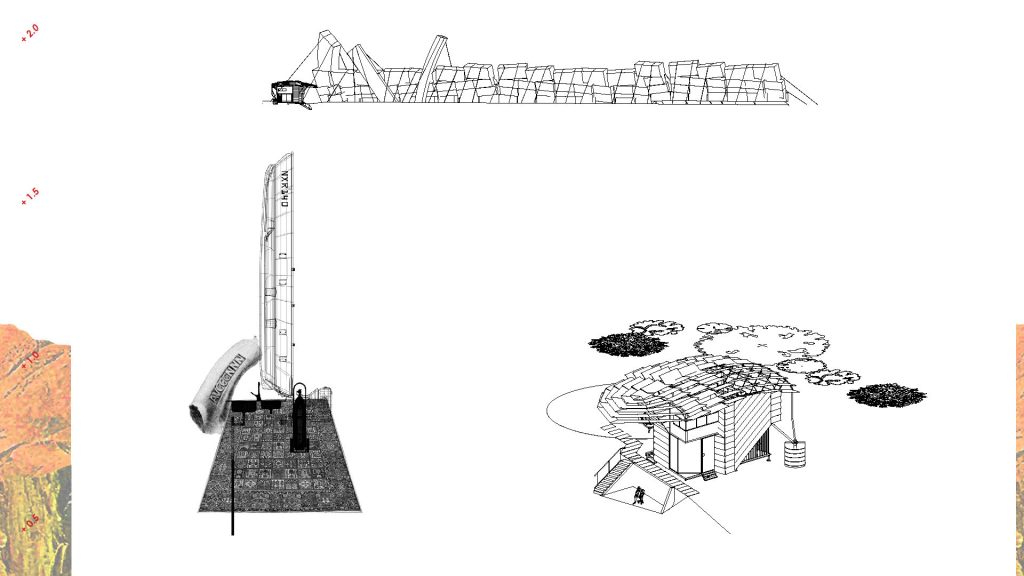

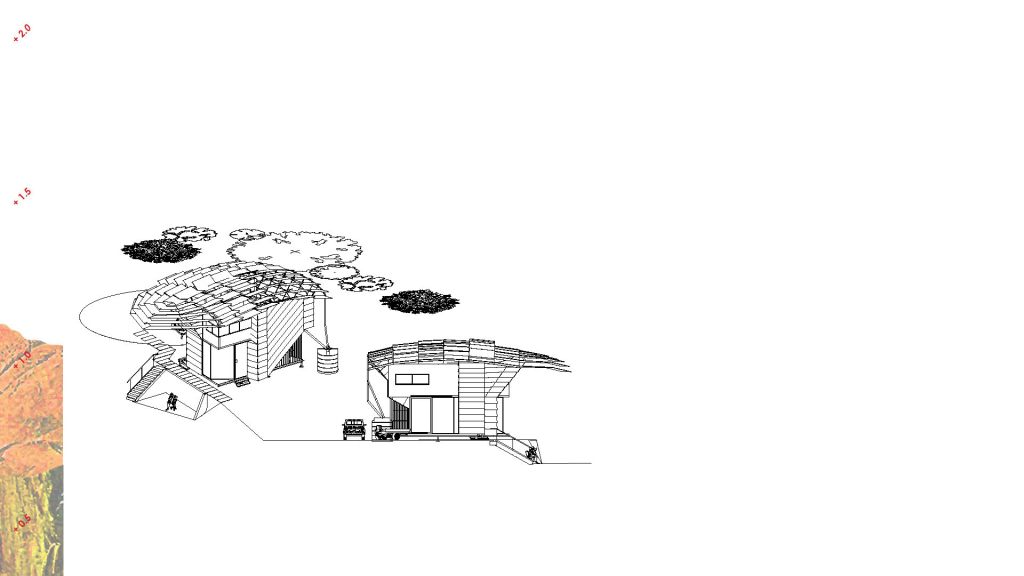

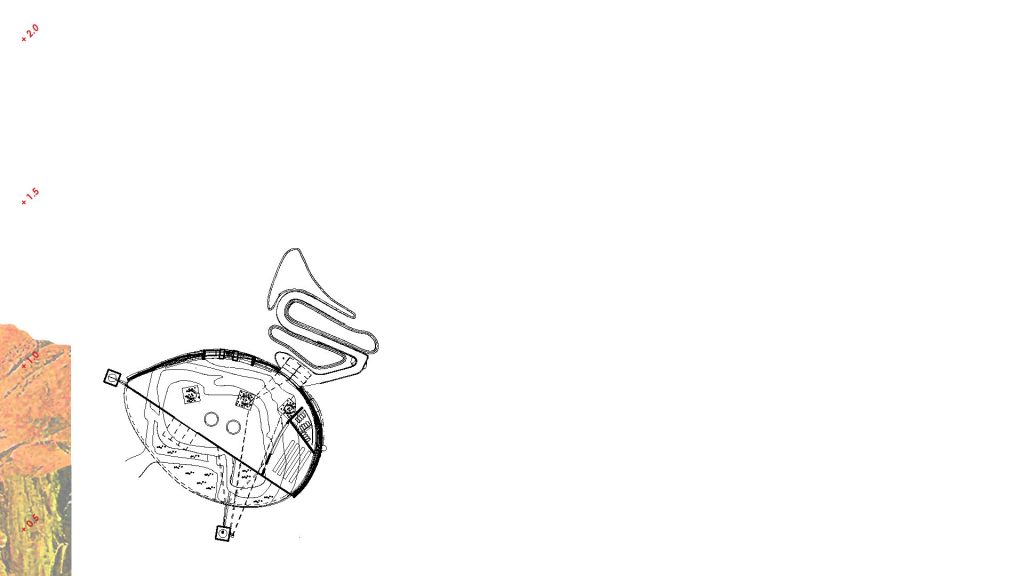

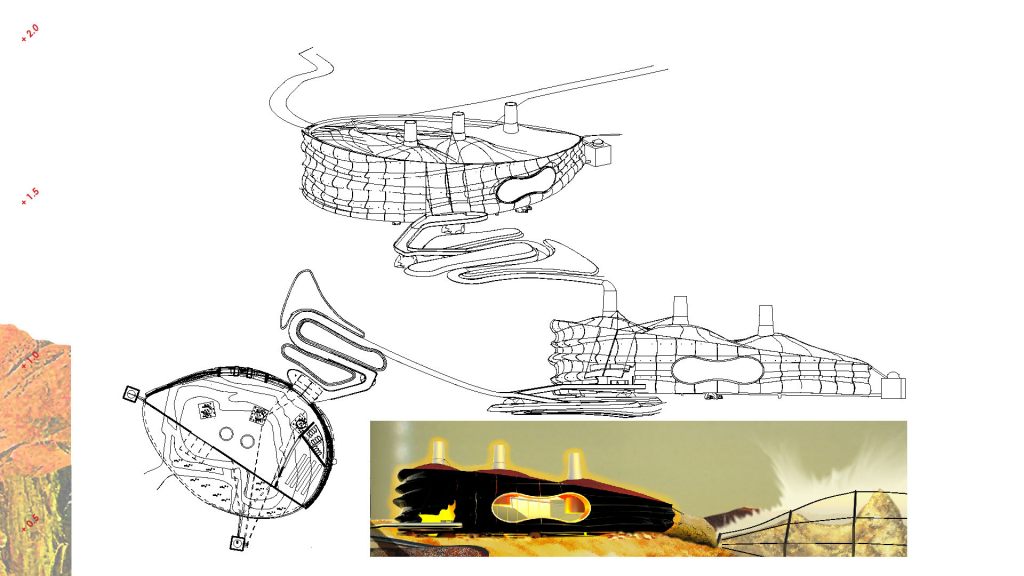

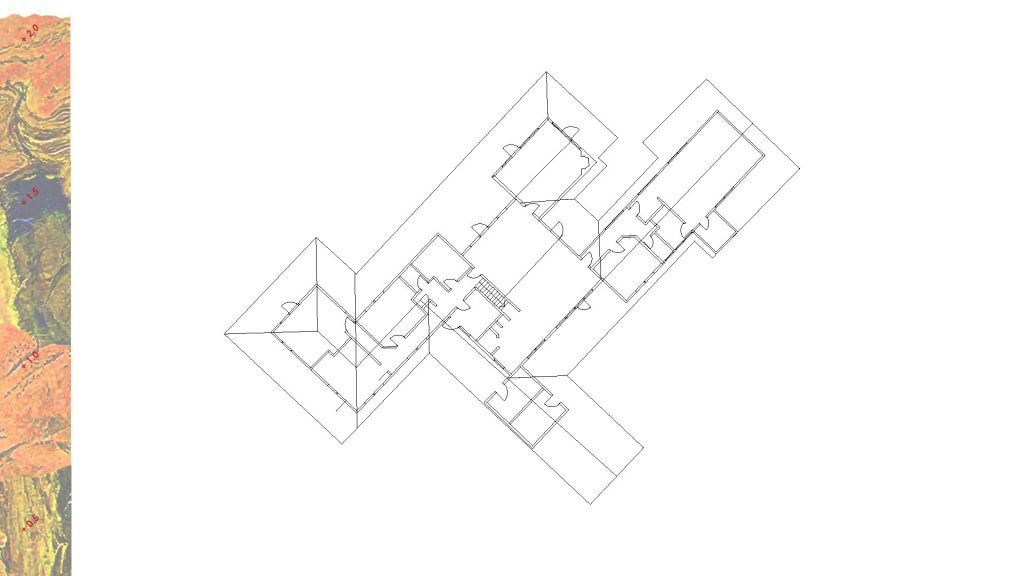

The caretaker’s house is envisioned as an amalgamation of scrapped materials, reflecting the slightly rough-hewn nature of its intended dweller who would oversee the site. A workbench is located beneath the first floor, where tools can be repaired. On the north side, beneath the roof’s bow, is a sunken porch situated 2 metres below the steel pads supporting the shack.

Approaching the visitor centre, the pathway descends 2 metres in a winding manner before ascending a steel ramp to grant entry, where visitors can store their belongings. The façade panels resemble the haze emitted from the flues next door, and the window offers a view of the landfill.

After storing your belongings, you pass by punctures in the floor with sunken gardens below and encounter two pathways: one leading to the landscape garden, the other to the Gallery and Archive. Following the path between compacted earth blocks, a ramp or elevator leads you into the archive.

The practice of restoration and archiving is on display, as are the rest of the gallery’s exhibits. The service lift, located on the western side, facilitates the receipt of collections and items for storage, restoration, or display. The operable rack systems occupy much of the floor space, echoing the depository nature of the neighbouring landfill. A sweeping oblong floor extends eastward, creating a gallery display between the archive and the monument yard.

The extensive ramp splits the gallery floor plan, providing a third entry option that leads to the middle of the building. Scattered display areas create a field with minimal direction for visitors to drift through.

Following the berm-like curvatures of the roof, inspired by the motor-cross track, the west side of the gallery floor features an observation deck overlooking the landfill. This proximity to the landfill establishes the connection with the subsidiary buildings, including the shed that faces it directly from the site.

Each building on the site draws on its surroundings while reflecting an internal relationship marked by a sense of longing, mirroring the vast and distant conditions around the site. Though distant, they are united by one element: the landscape. This connection is evident between the visitor centre to the north and the Gallery/Archive situated above the ravine to the south.

A dialogue is inherent in everything around the landfill and mine. This dialogue is embraced and imagined in the architecture, with inflated structures metaphorically ‘blown up’ by the heat generated from the landfill’s waste degradation. The shallow footings, just 2 metres deep, evoke a sense of precariousness and reveal an underlying threat.

THE FOREVER HOME

These interpretations, representations, and imaginings are truths determined and translated from a real story I was told about a home that was never built.

In 1998, Simon and Rosemary Wilkins purchased the property at 4265 Bacchus Marsh – Geelong Road, Parwan, with the intention of building their ‘forever home’.

Upon starting the town planning submission process with the council, the Wilkins encountered an obstruction: the council informed them that their plans could not be assessed.

This obstacle arose because their western neighbour, the Calleja Mining Group, was required to complete a land management and development plan before any planning permits in the surrounding Parwan – Bacchus Marsh area could be approved. Calleja Mining Group controlled when this plan was completed and was intentionally blocking any development to establish a future landfill in the voids created by their extraction.

In response, the Wilkins attempted to acquire their own mining licence to complete their own land management and development plan and proceed with town planning. However, they discovered a final obstruction: they could not obtain a mining licence for their property at 4265 Bacchus Marsh – Geelong Road because Calleja already owned the mining rights for all of Bacchus Marsh and Parwan. Legally, the Wilkins only owned the top 2 metres of soil on their property.

The only minor victory the community had against Calleja was the coincidental privatisation of Essendon Airport, which moved pilot training for twin-propeller planes to the next nearest airport of similar scale in Bacchus Marsh. This resulted in a 2-kilometre protection zone around the airport, preventing the coal mine’s future landfill from using the voids for municipal waste due to the birds it would attract. Consequently, the landfill could only accept other types of waste, mainly construction and toxic waste, some of which contained PFAS, also known as ‘forever chemicals’. The property was sold in 2001.

The absurdity of this scenario and the peculiar convergence of factors prompted the beginning of this project, establishing frameworks that operate within irrational constraints. Initially focused on ecology and environment, the project shifted to exploring form and translating narrative and significance into architecture. This reaction to the continual findings of strangeness and wonder, combined with the striking and picturesque qualities of the landfill and its connection to the site, shaped the project’s development.

The initial rendition of the project may seem absurd and strange, but perhaps its reality is no less strange and absurd.