Do What’s Happening

RMIT University Master of Architecture Graduate Project 2022

Supervisor: Michael Spooner

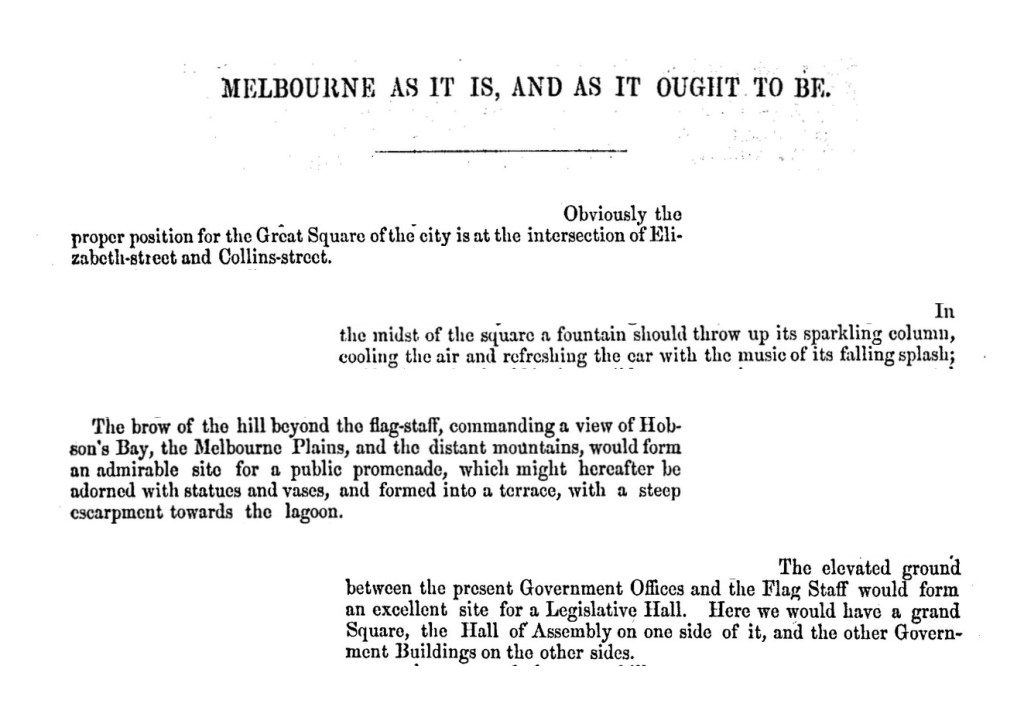

In 1850, an anonymous author penned an essay titled “Melbourne as it is and as it ought to be.” In it, the writer condemns the way the city had been planned up until that point and proposes an alternative vision for the city, envisaging an urbanity that moves away from the more prosaic planning of Melbourne’s 1830s and 40s. Painting an elusive yet vivid picture, they describe squares, grand boulevards, and crescent streets—an ambition that reflects the changing identity of the settlement and its relationship to the Empire.

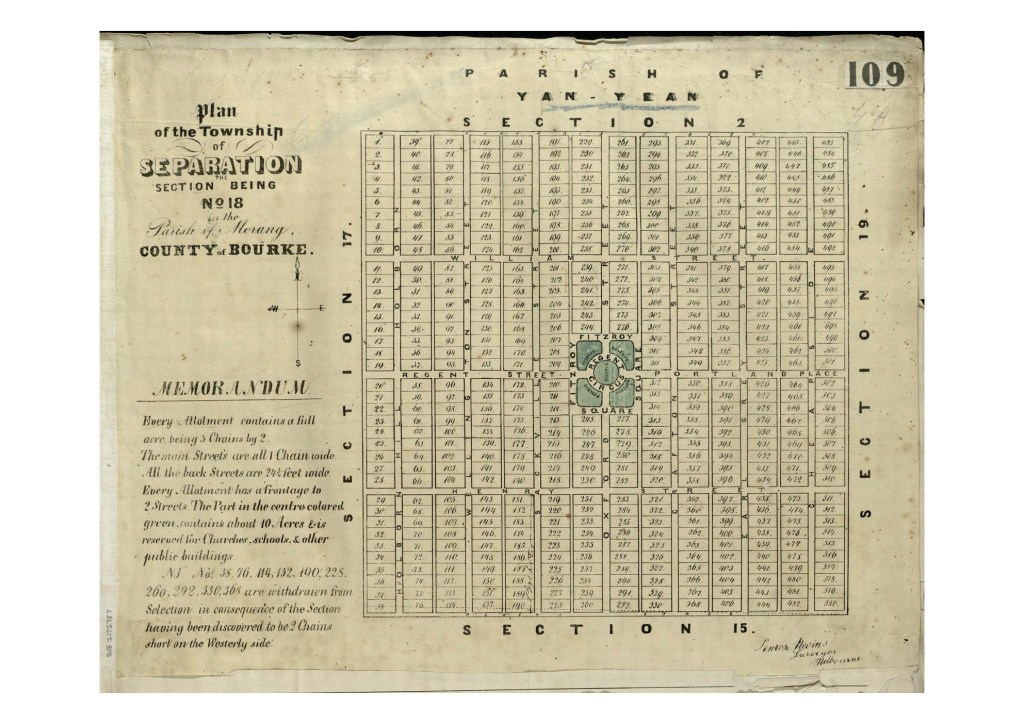

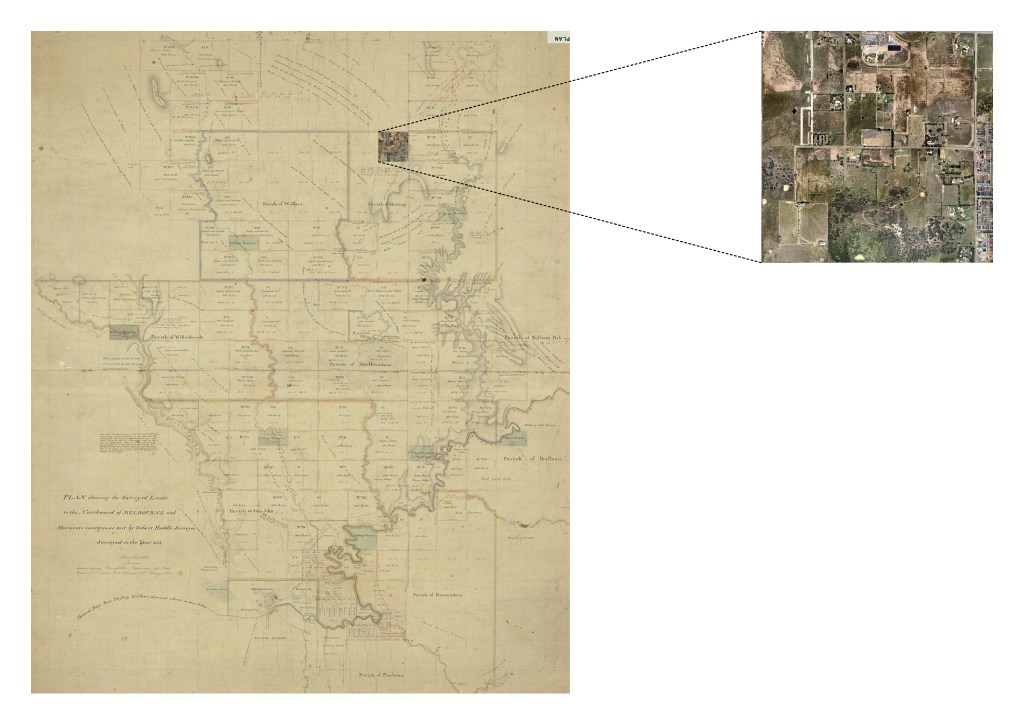

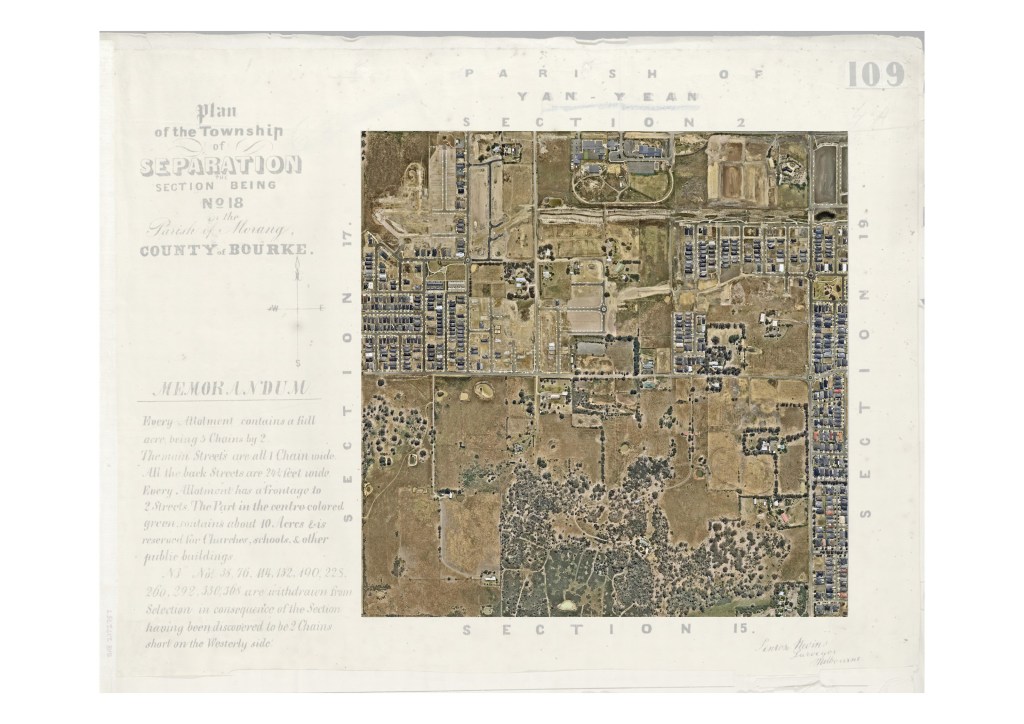

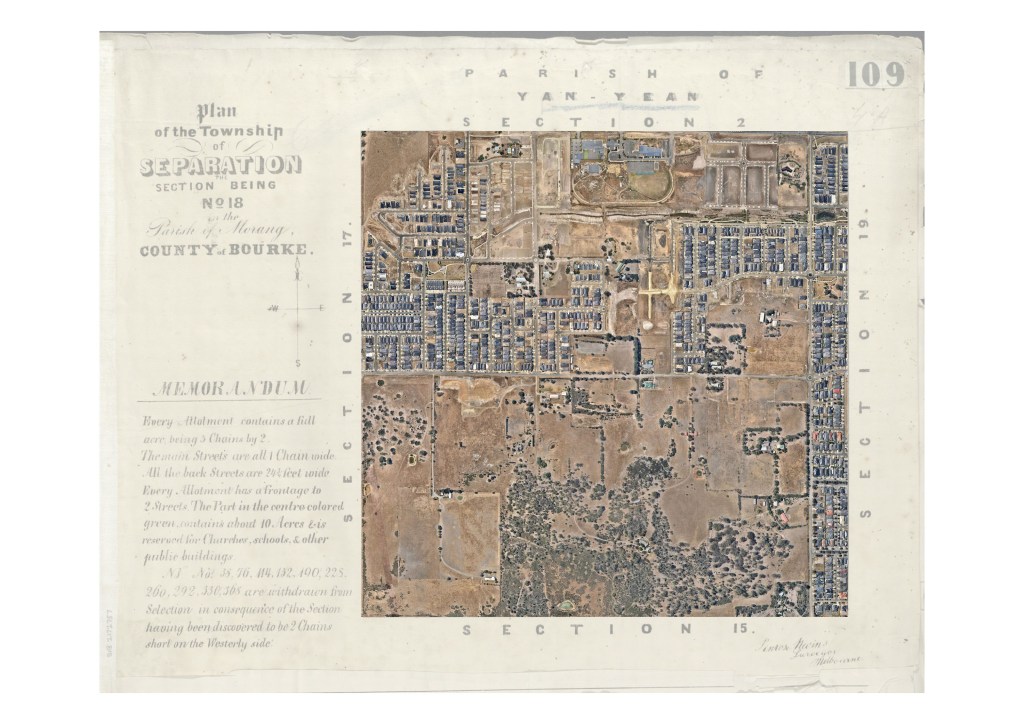

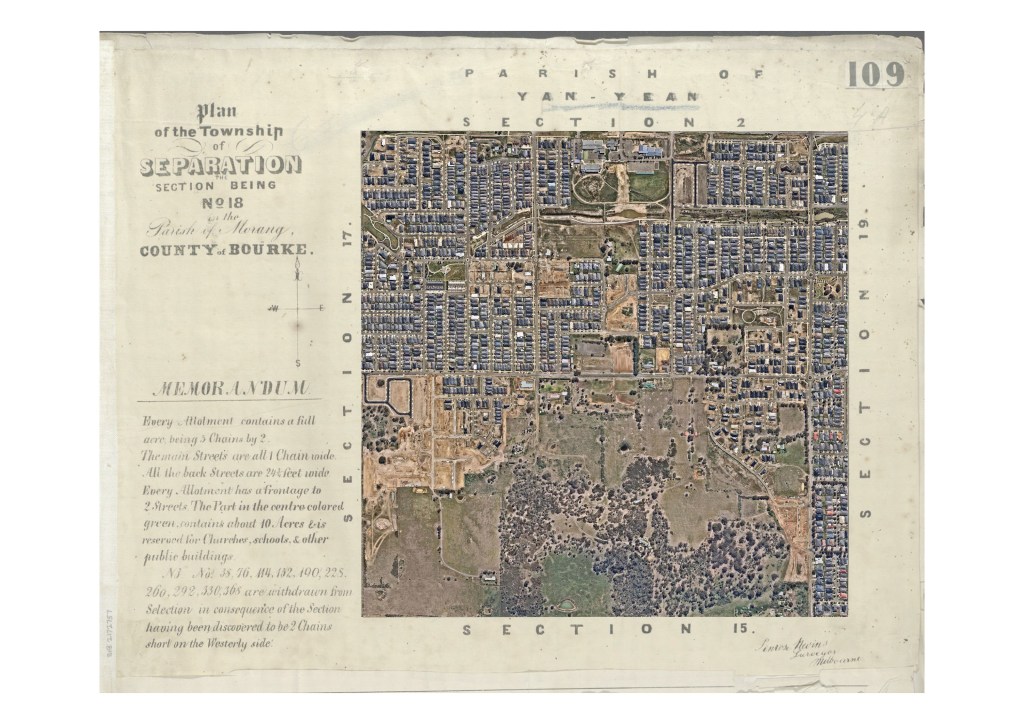

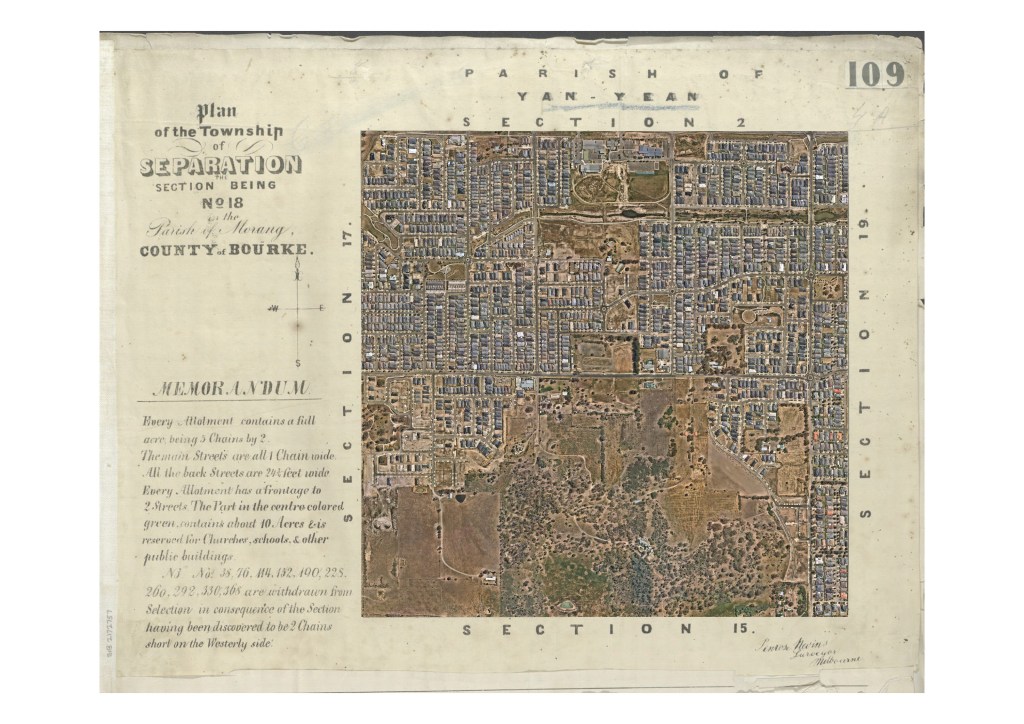

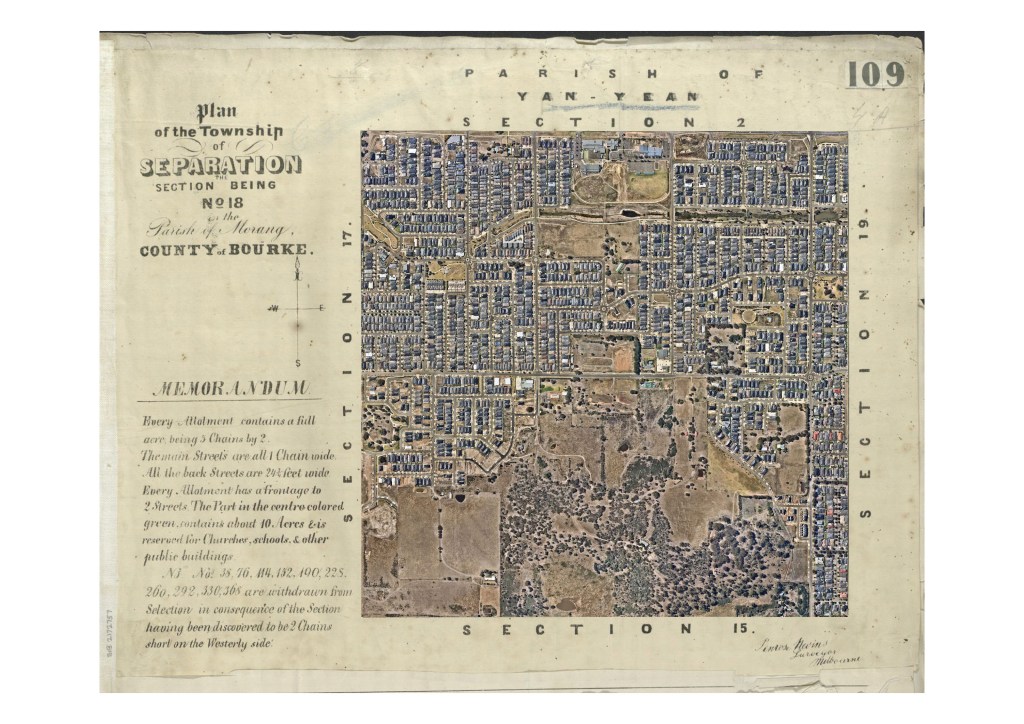

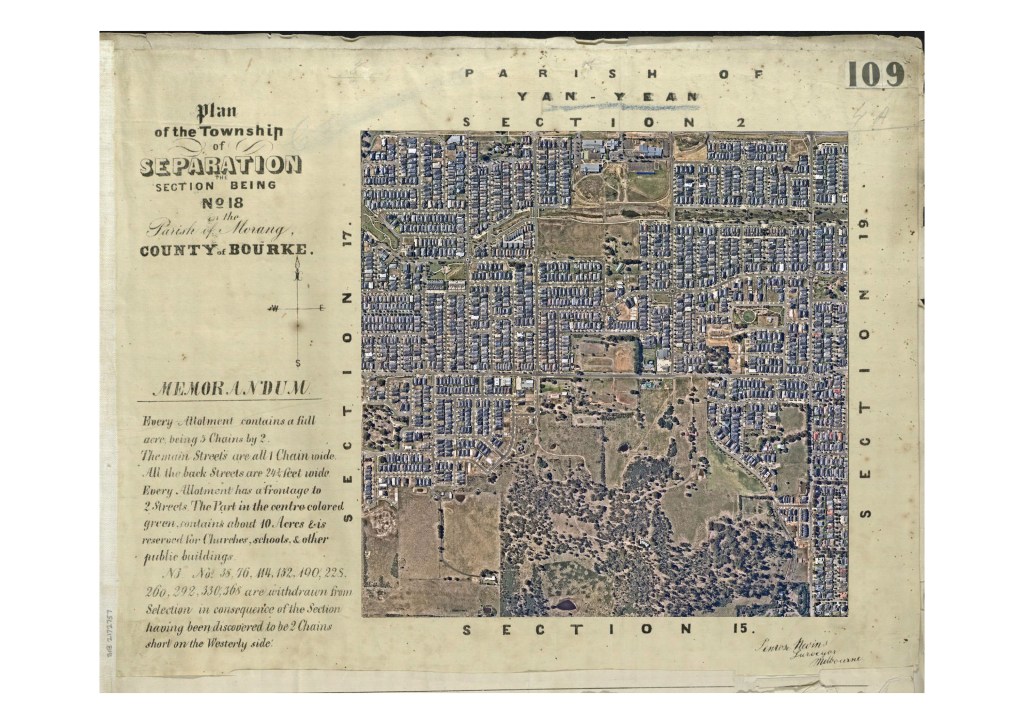

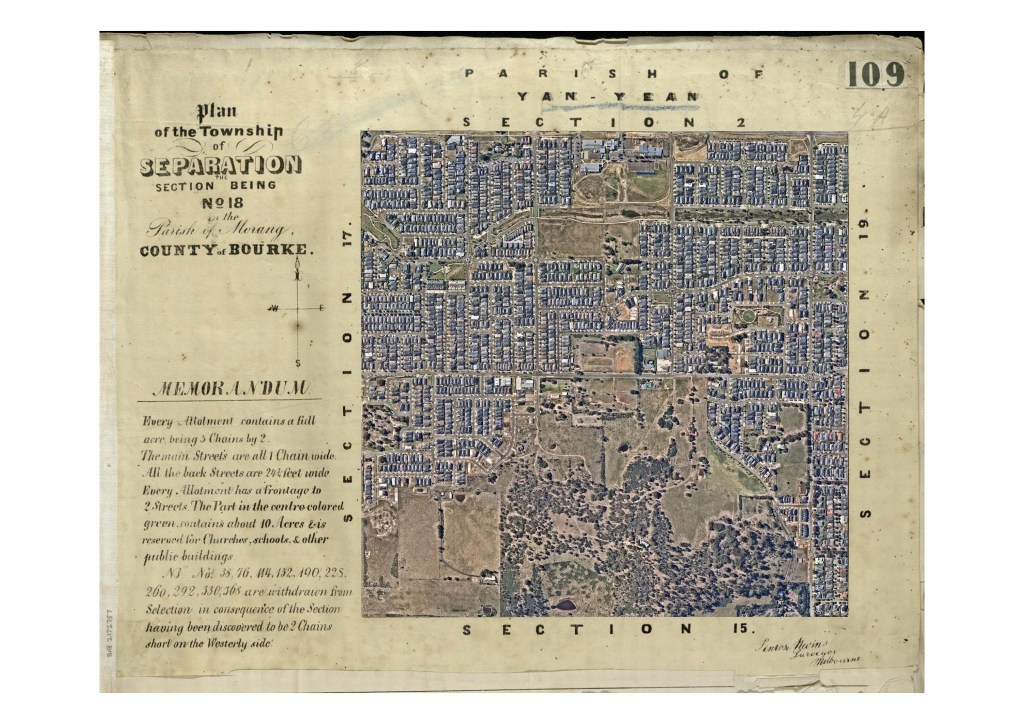

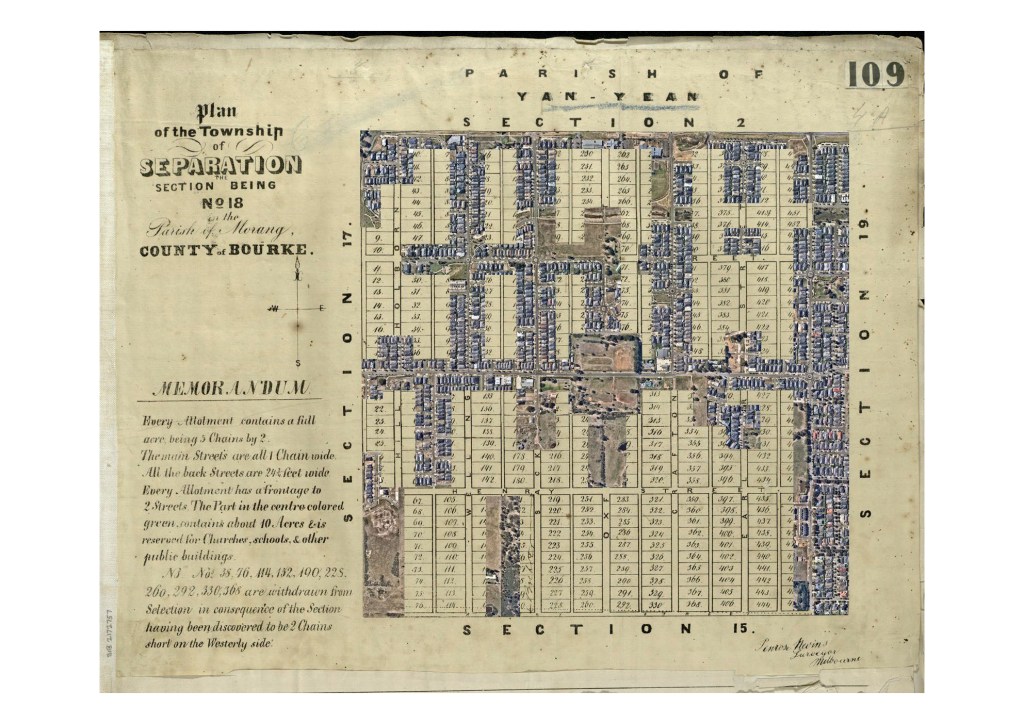

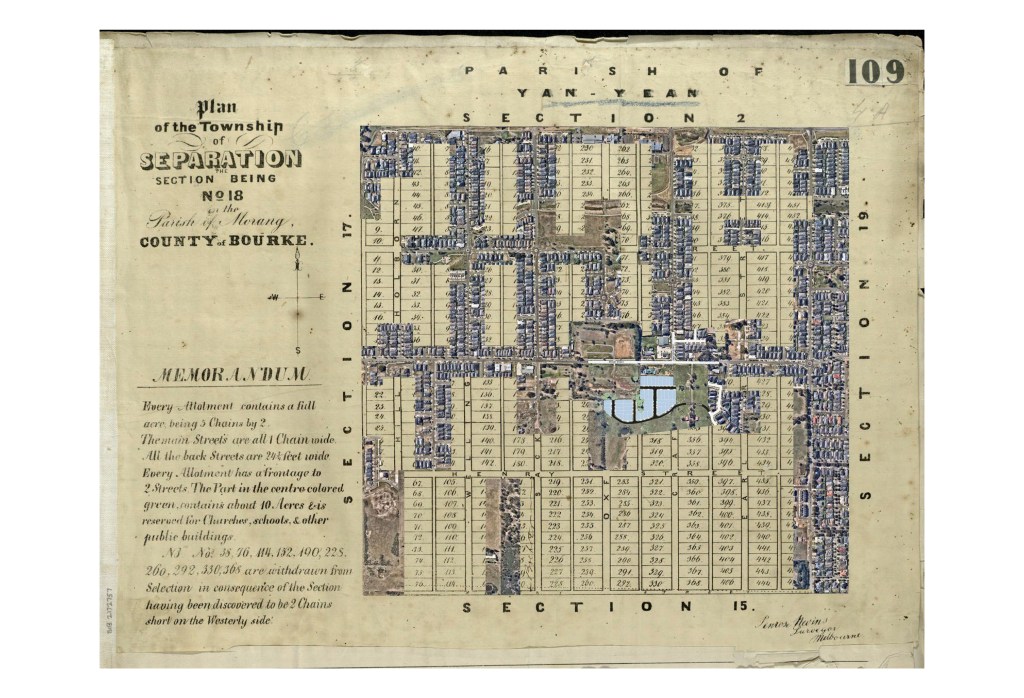

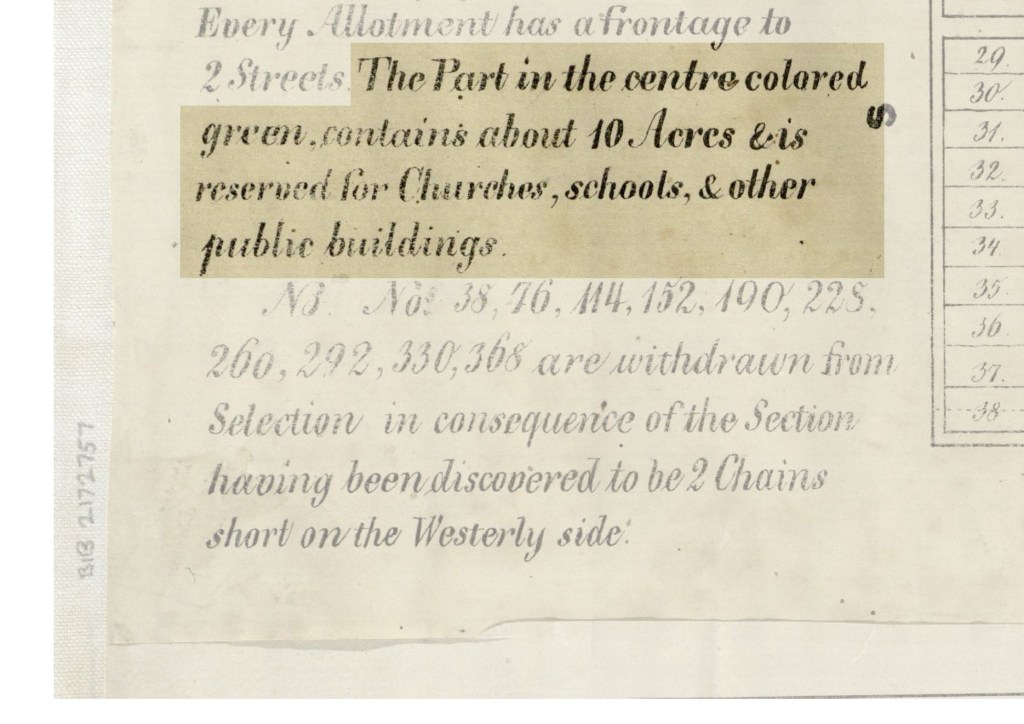

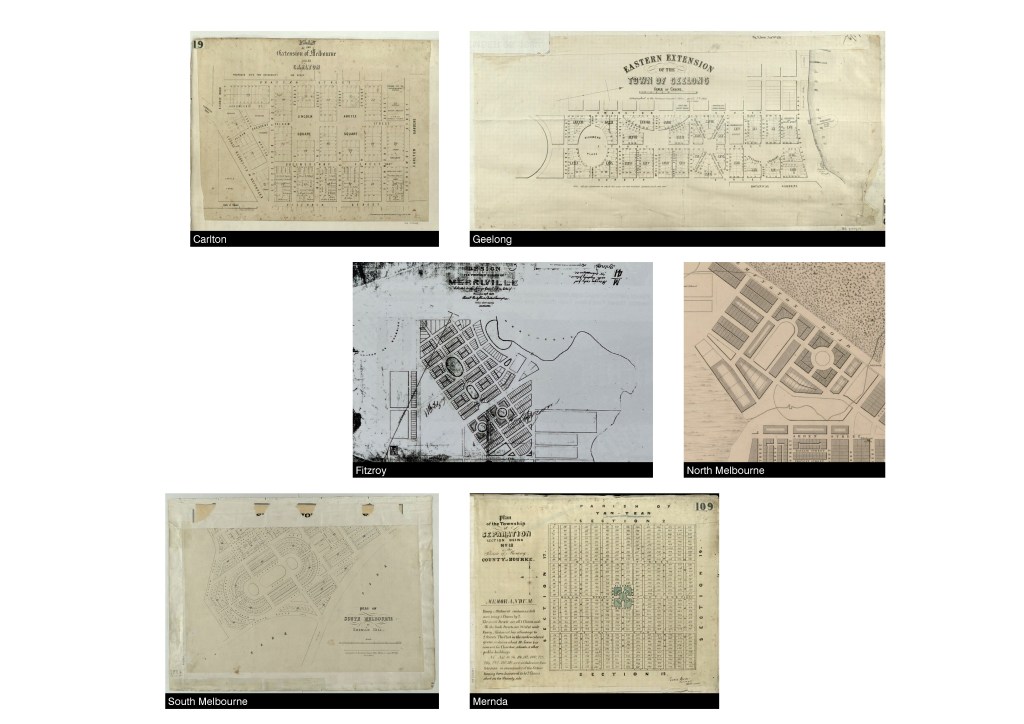

This sentiment is captured in a handful of proposals, many of which emerged in the years following Hoddle’s retirement in 1853 and are characterised by their geometric and figured layouts. One plan of particular interest is situated in present-day Mernda, 27 km north of the CBD. It is historically significant as one of the few plans marking this 1850s shift and as a reminder of the scale and speed at which the land of and around Melbourne was claimed by European settlers

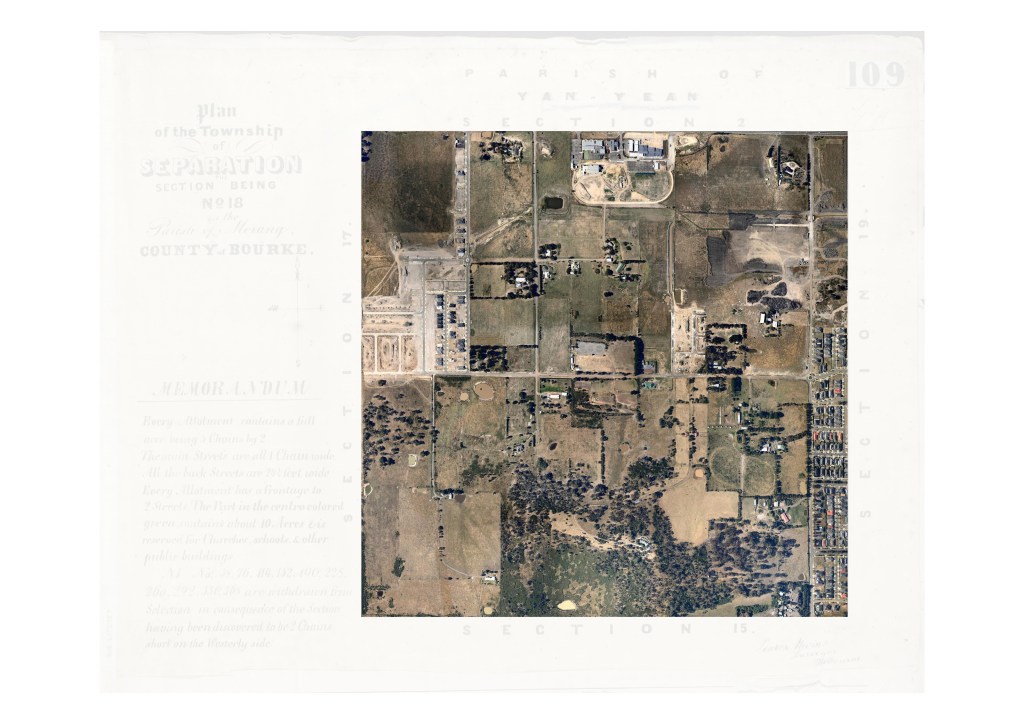

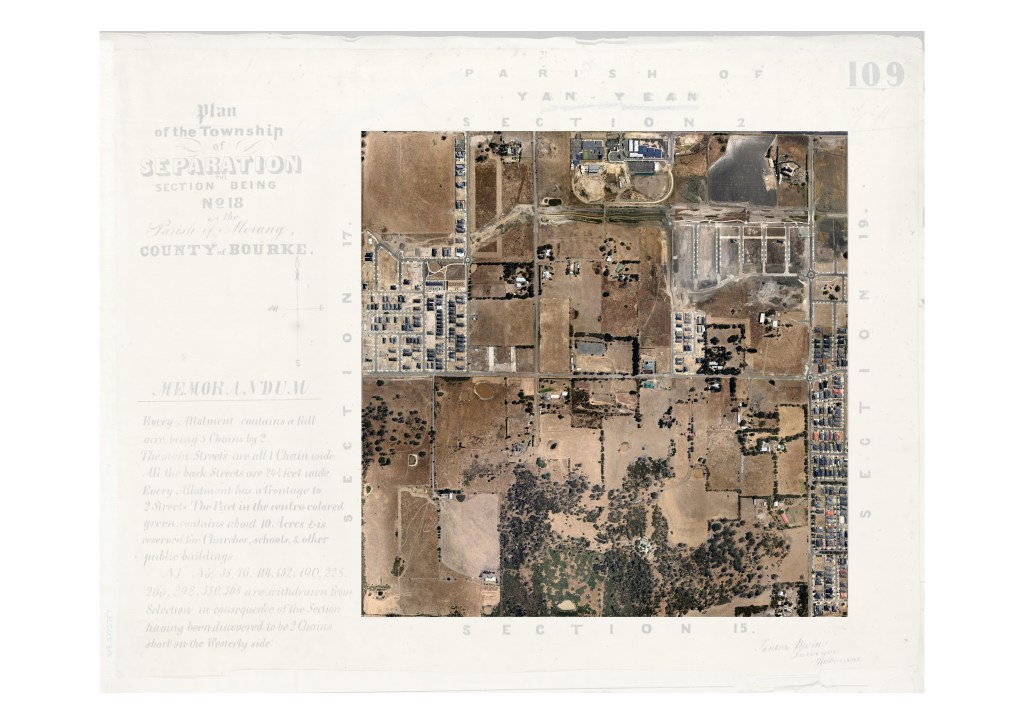

Designed to occupy one of the one-by-one mile grid squares drawn up in 1837, this grid covered so much land that Melbourne’s suburbs are still yet to grow into some of the early subdivisions. Despite the land being predominantly agricultural for the 160 years following the plan’s conception, the property divisions and few roads that were built remain. In the last decade, as the suburbs have crept in, an image of the plan has started to appear. These streets still carry the name of the 1850s plan, and as further development takes place, the figure at the centre continues to be reasserted.

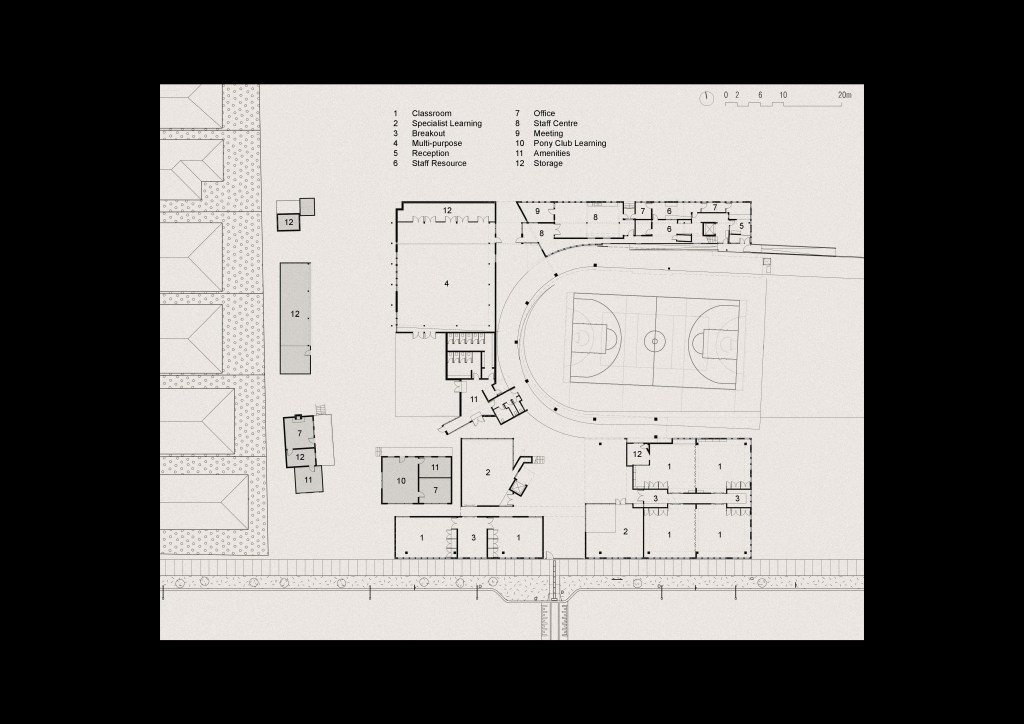

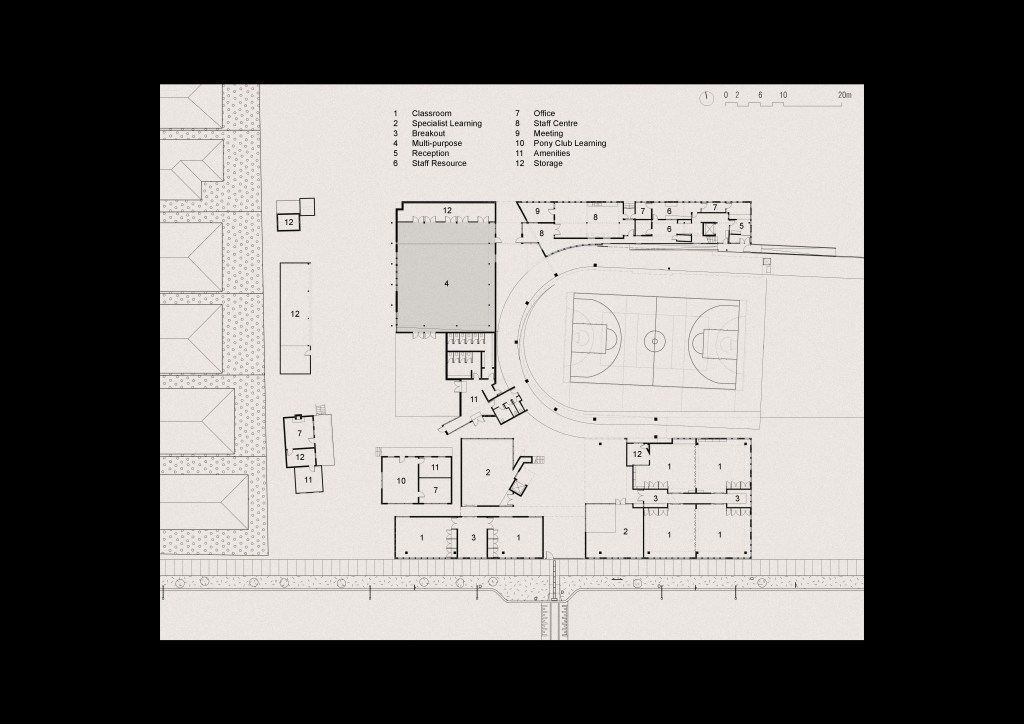

At the same time, however, the plan is being lost. The newer streets show that the rigid geometry of the earlier proposal is incompatible with modern-day planning, which navigates the topography of the site. Additionally, changes to the planning scheme have had an effect—most significantly, the central square, which existed as a public use zone until it was recently amended in preparation for residential development. This area was earmarked as the civic centre of the township, and its designation as a public use zone, at least up until this year, has enabled a pony club to remain as a vestige of the site’s rural history.

Building upon the legacy of this centre, I’ve imagined an alternative future for the site, where the pony club remains, and a school, pool, and weather station come to accompany it. Something I’ve been intrigued by this semester is instances where one thing builds on or within another thing that was never fully realised. One example is the bones of Darryl Jackson’s partially constructed Melbourne Museum evident in what became DCM’s Melbourne Exhibition Centre. If understood as a partial realisation of the 1850s plan, the question became what, if anything, of Mernda’s pony club would be held onto?

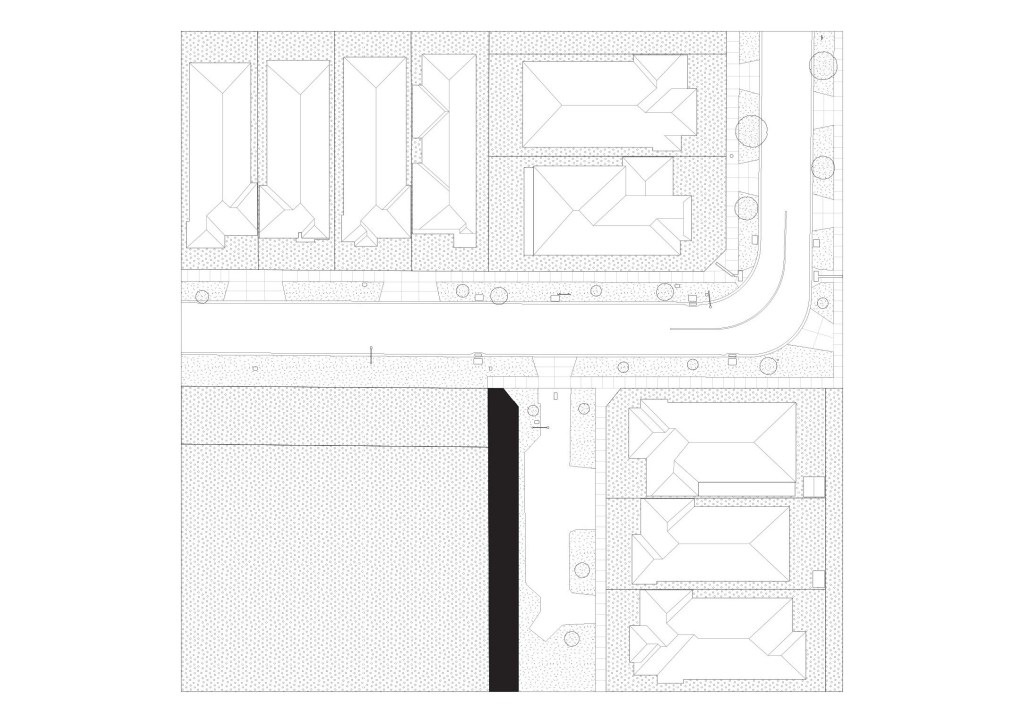

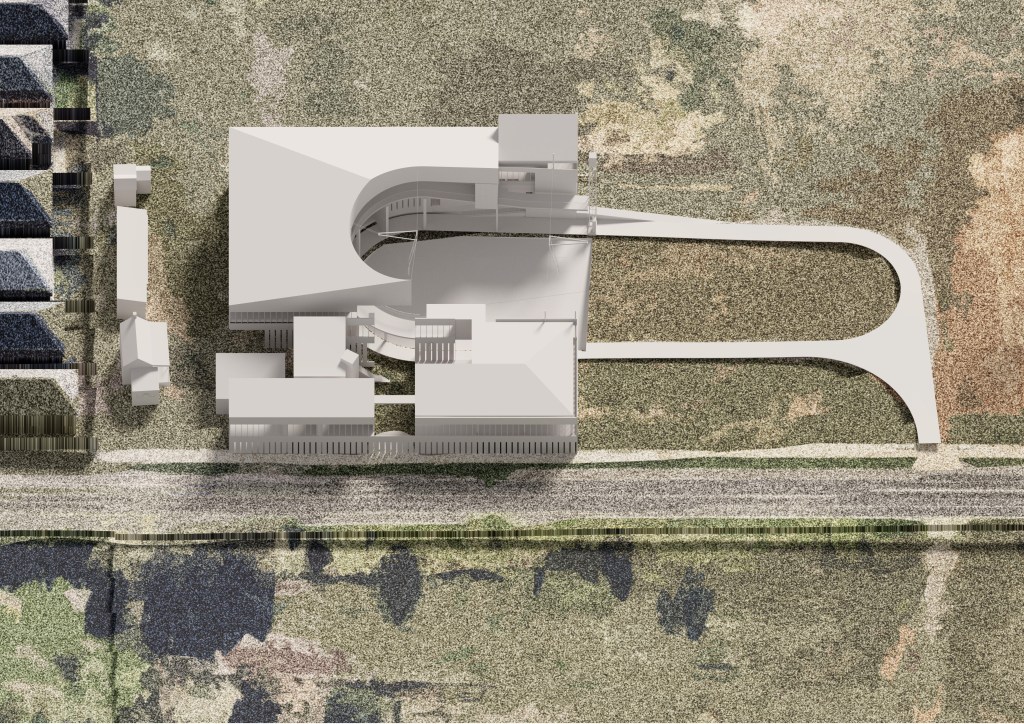

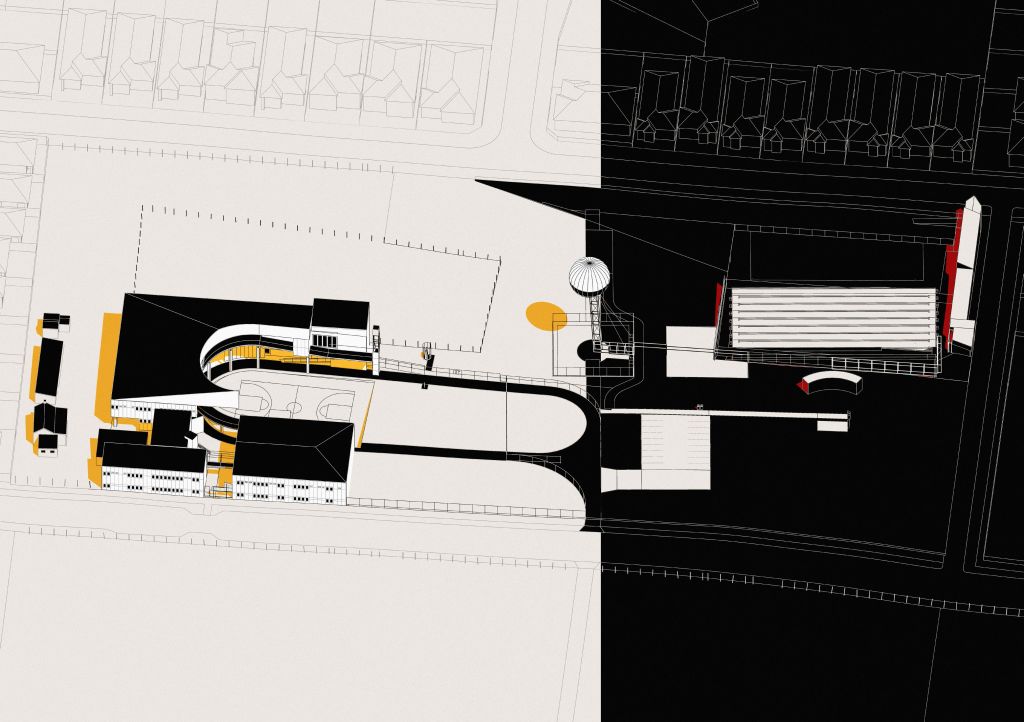

The decision to keep the looped gravel track came early and defined the footprint of the school, which wraps around it. How this project should sit against or alongside this track, as well as the existing structures of the club, began to inform the expression of the plan. The pony club, highlighted in grey, breaks the implied square of the school buildings. One of the fractures to this square presents as an entry for students on the southern boundary, where the buildings make contact with the street. Perhaps an unusually sudden shift in scale for the suburban context, I was reminded of a particular area of Coburg, where there is an abrupt adjacency between 19th century houses and the massive scale of a Bunnings warehouse. The sudden shift in scale between the buildings enables a novel way of seeing the buildings, their relationship to each other, and their relationship to the street.

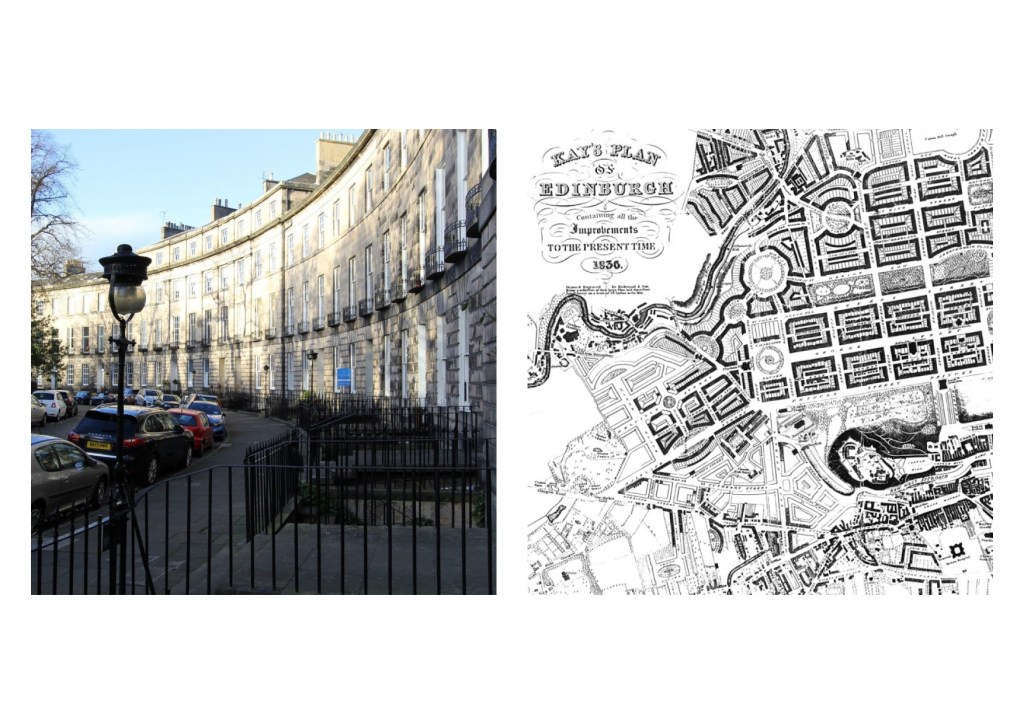

It’s interesting to look back at the 1850s plans and consider the original visions of the planners when it came to the streetscape. Miles Lewis suggests that planners who were proposing street layouts emulating those of Georgian Britain also envisaged that the architecture that was to fill these streets would have a similarly Georgian character. The urban fabric of Edinburgh was an image not far from that which was in the minds of these planners, with its terrace housing forming solid masses that defined the space of the streets. With this in mind, perhaps all the 1850s plans emulating Georgian city planning could be understood as unrealised in some way. If we look at Geelong, for example, a very different idea of a street was realised by the time the buildings were constructed.

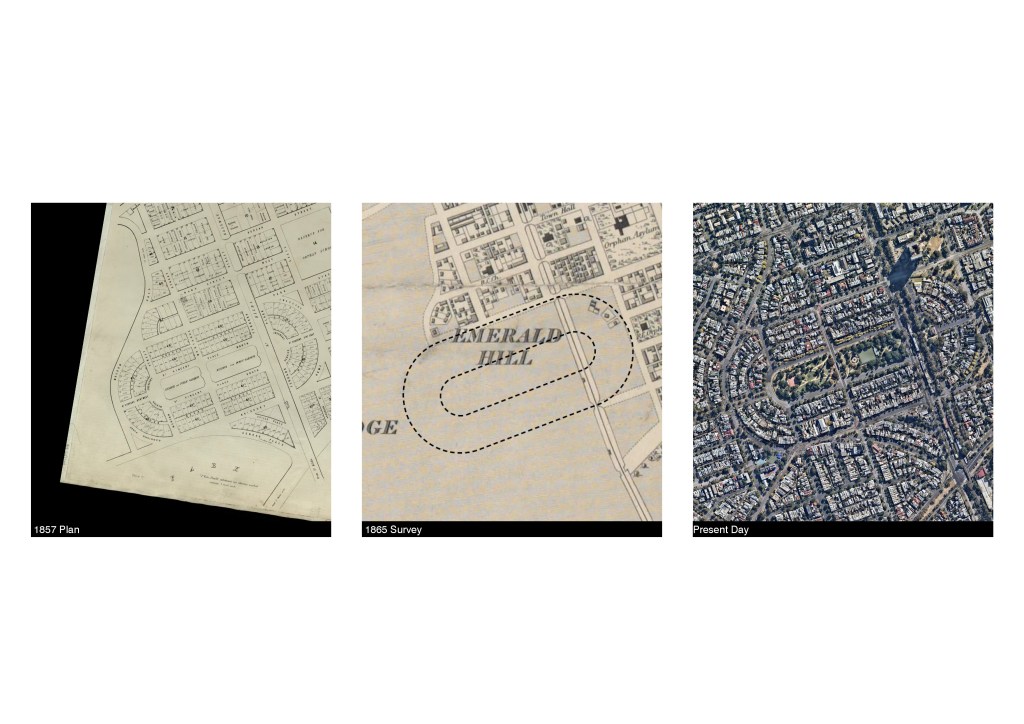

Even in the more dense and affluent Emerald Hill, or today’s South Melbourne, it becomes clear that this intent was not able to be fulfilled. Comparing a crescent street in Bath with one in South Melbourne, it becomes clear that this intent becomes muddied. In the Georgian precedents, the urban plan and architecture were undertaken as a united endeavour. This 18th-century approach to city building was not compatible with 19th-century Melbourne, a city defined by individual enterprise. As can be seen in South Melbourne, plots of land sold to individuals were developed over time. The plan on the left shows the 1857 proposal for the area, and an 1865 survey shows the handful of houses built by this time, revealing the process of accretion and gradual change that shapes the city.

At the Mernda site, there’s something that hints at the incoming of further development. A footpath at the north-east corner of the site continues past the residential street it serves, stopping abruptly in the unkempt grass of the site. It implies what is to come and is a reminder that the site, as a rural vestige, will likely soon be lost.

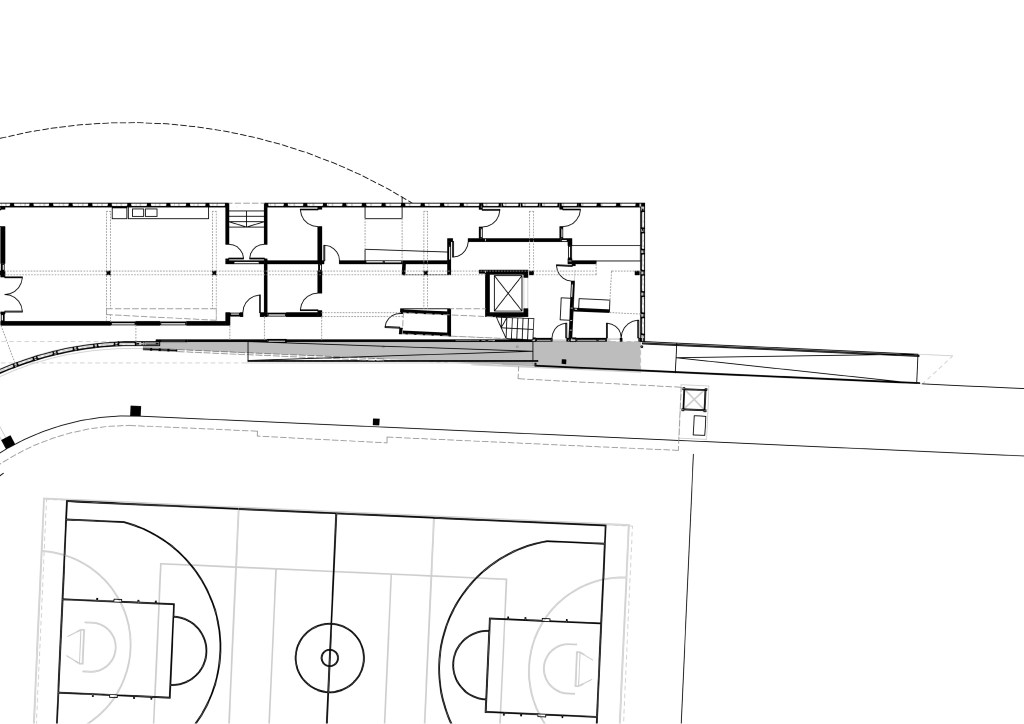

Intrigued by what it might mean to hold something of the footpath in this temporary condition, the extension of the concrete path is imagined in contrasting asphalt. The stairs up to the pool entry register this change, also being split by the line where the project meets the existing, and the nosings and tactile indicators also mark the shift. The pool occupies the north-eastern corner of the site. At this corner, two slim parcels of land exist, resulting from historical surveying inaccuracies intersecting with the new streets. The changeroom building sits on the sliver running north-south. On the 4-metre wide plot of land, the building is forced to sit against the street. Applying a hypothetical constraint implied by the site’s divisions, something of the 1850s plan is revealed, only for a moment.

The building acts as a barrier between the pool and its neighbouring houses, and the admin area and changerooms stretch along its length, connecting onto a singular elongated space. Looking back at the school, it’s clear that something of the changeroom building’s narrow spatial conditions seeped into its plan. Reflecting upon work in progress, I noticed some kind of fixation on the areas of the school which inherently held something of the earlier pool project. The entry sequence was worked over, in some way amplifying the wedge between the school building and the pre-existing track. Realising that there’d need to be access to the reception area from both inside and outside of the school grounds, the wall broke open, revealing the slight misalignment between the inherited site artefact and the new building. The angled line of the gravel track echoes throughout the plan, in this case disrupting the southern edge of the multipurpose room, a space shared with the pony club.

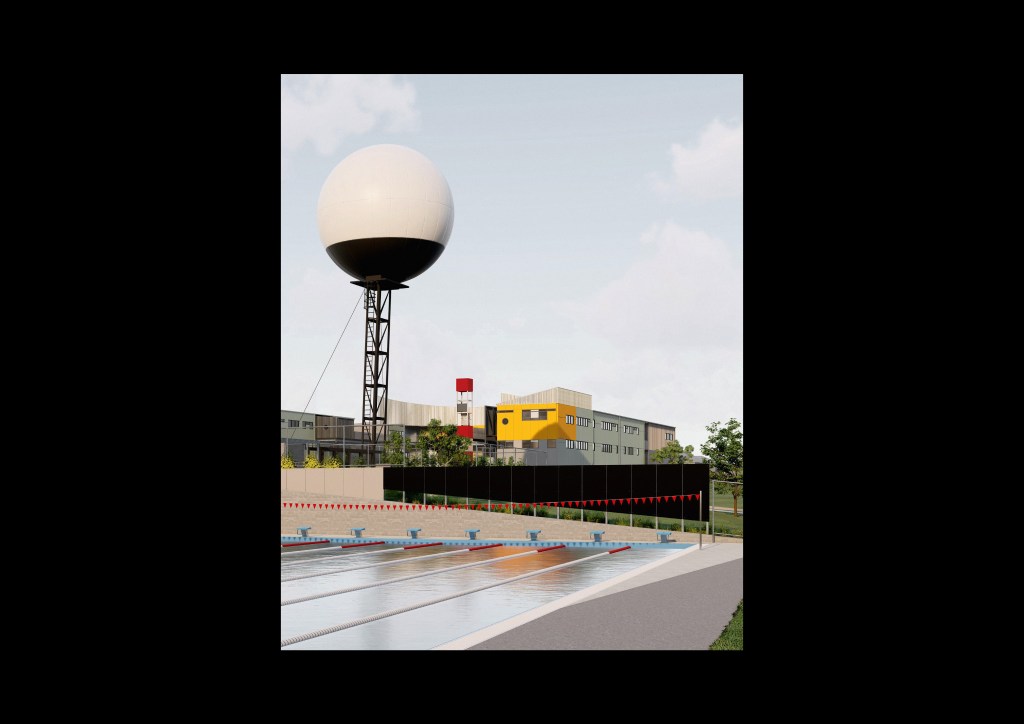

A sudden rise in intensity in the floor, ceiling, and building utilities marks the interface between the two institutions, with the back wall sliding aside to reveal the club’s old structures. Somewhere between the school and the pool, a third project emerged—a weather observation tower, reading as a portion of the school or pool dislodged and slid across the site. Its fences and associated structures also give form and react to the abstract lines derived from the site. The fence continues along the back of the pool’s spectator stand until it breaks off and forms the pump room at the end of the long pool building. Together, the two structures frame a row of trees, and an established windbreak on the site’s edge.

Like the gravel track, the windbreak is an artefact of the rural landscape. It is, however, the only thing on the site, except for the fences, that demarcates the historical boundaries of the 1850s plan. Earlier in the semester, I undertook an exercise exploring what it might mean to preserve this artefact—this image shows a path whose structure wouldn’t disrupt the trees’ root zones. Now, at the end of the semester, it seemed appropriate to reflect on this and the role of the 1850s plan in my project. If the plan was the thing that sparked an interest in the site, what was its value beyond this? Besides instigating the question of how to work on the incomplete, it also became a reminder of the impossibility of realising—in absolute terms—the intent of any plan or proposal. Of course, the Mernda plan is an extreme case where social and economic factors meant the township never took off. However, we can also see that where urban plans have been actualised, for example, in South Melbourne, the original intent or aspiration might not be met either.

I became curious about how this also occurs on a scale and timeline smaller than that of the urban—the timescale of a single building. The disjunction between architectural intent and real-world building is something that John Gollings reflects upon in his photographic work. By drastically editing the photos, they depict a fantasy that could be considered truer to the architecture than the building itself. This thinking influenced the expression of the project, which facilitates and emerges from the imagery of building utilities and services—elements often photoshopped out of architectural photography. To be clear, this is not an attempt to avoid the inevitable disruptions to architectural intent, but a strategy that emerged from observing these disruptions. It’s an opportunistic approach that marries with the inevitable frugality of schools and other community facilities.

Reflecting on the start of the semester, I initially resisted my major project being sited in an almost vacant plot of land. My hesitancy stemmed from there being so little on the site to hold onto. But it’s within this difficulty that the project found its grounding. In a space like this, the decisions came down to what blinds were chosen, the gloss levels of the paint, and how the powerpoints were placed on the walls. What can you do with close to nothing? How can you find opportunity and delight in a place and the architectural process itself?

The project seeks to harness the delight found in civic infrastructure and the imagery of the municipal: the stripes of a school crossing, the colours that proliferate across the city, and the effusive form of another weather tower, this one in Laverton. If a reflection on the history and artefacts of the site provided a generative force, interfacing this with utilitarian imagery began to give rise to the architectural expression of the project.

Naturally, this process sits within an even wider context—that of the architectural discipline. As ideas and images swirl around its professional and academic settings, certain things will strike a project in the process of being designed. This, of course, is filtered through the individual designer, their personal history, what they’ve been exposed to, what sticks, and what they hold onto.

Finally, there comes a point when the architecture of a project begins to reverberate within itself. This project is about the tenacity of a vision, and how value is assessed and assigned within the process—what is acknowledged, what is done with this acknowledgement, and what is contributed. It contends with the forces of lag, legacy, speculation, and anticipation in the built environment and the process of design.

Like most students undertaking a Major Project, where mine ended up is very different from what I had imagined at the start of the semester. Reflecting on the futility of controlling an outcome, one thing I’ve discovered this semester is the importance of finding joy in the process. And then, if you like, you can hope others find joy in the work.