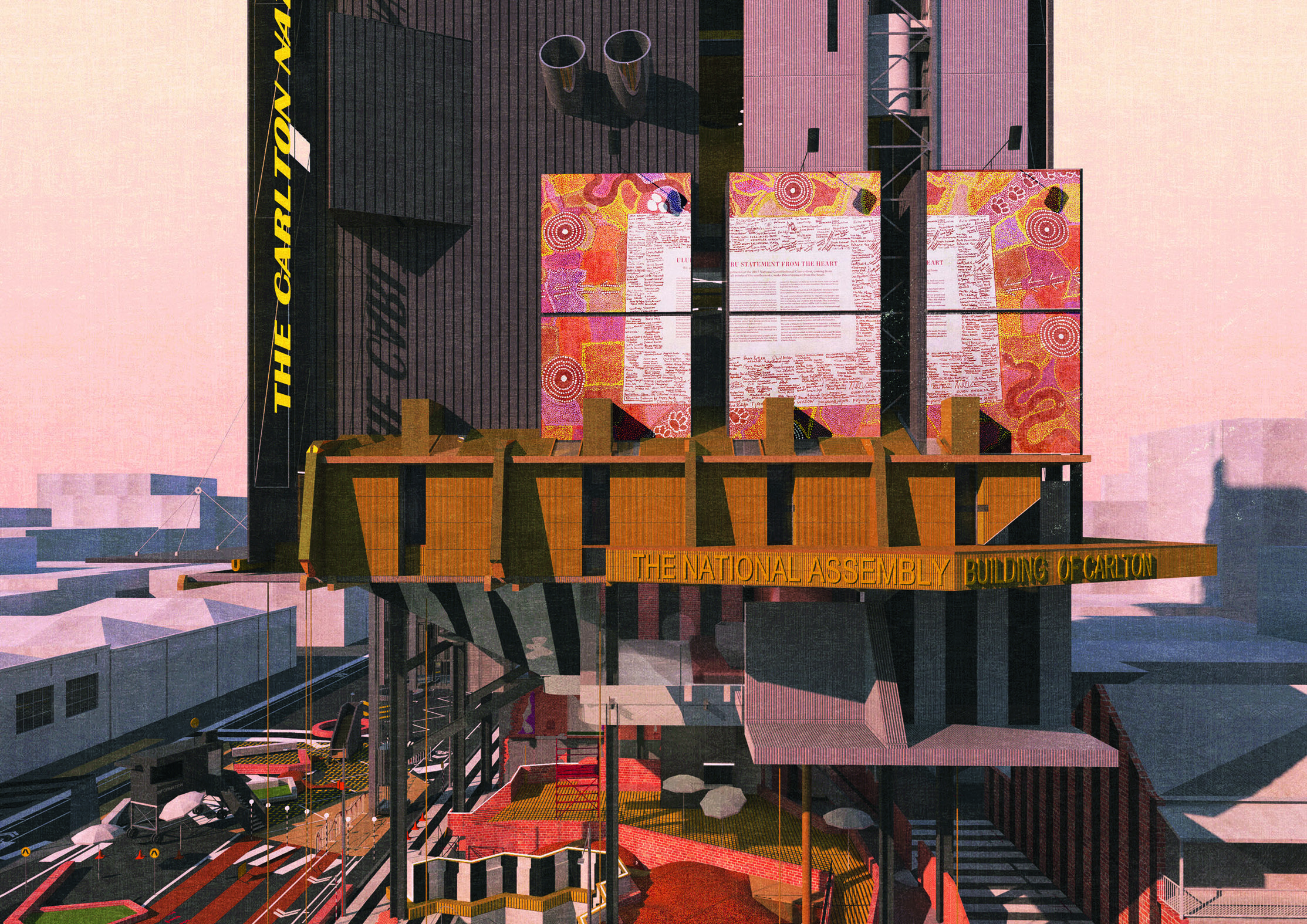

The Carlton National Assembly

RMIT University Master of Architecture Graduate Project 2019

Supervisor: Michael Spooner

I would like to start by acknowledging the Boon Wurrung and Woiwurrung peoples of the Kulin nation as the traditional custodians of the land where this thesis was conducted. I would also like to pay respect to Elders, past, present, and emerging and I extend this respect to Aboriginal and Torres Strait islander people throughout Australia.

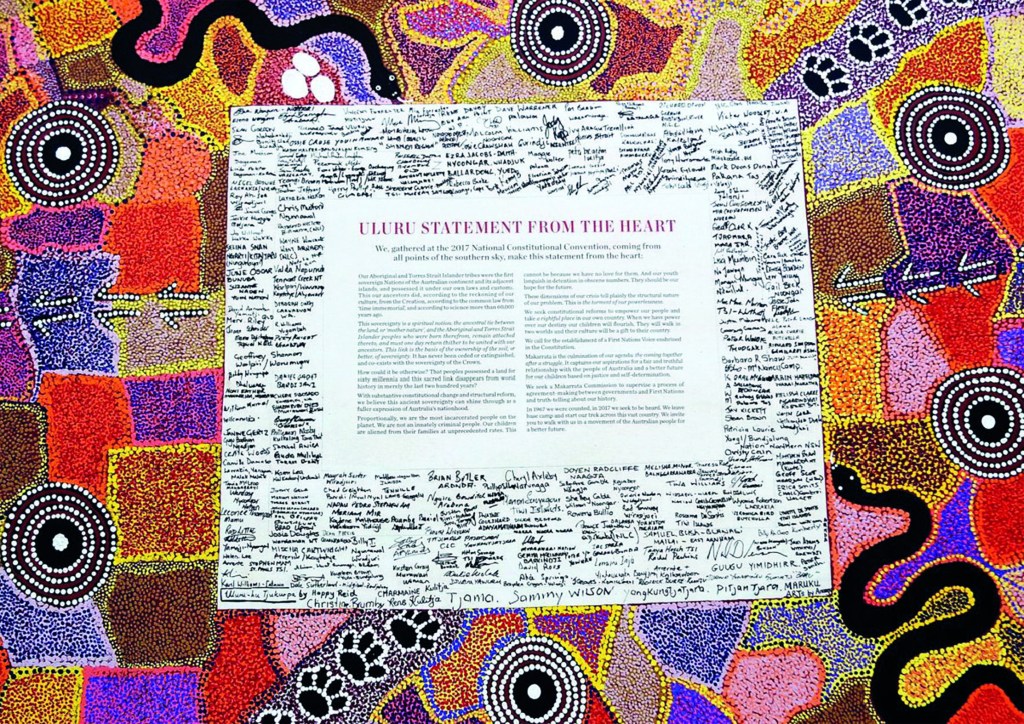

This project envisions a present reality set in a distant future. While its potential may begin now, its ultimate conclusion remains perpetually uncertain. It emerged from the passing of the 2018 Victorian Treaty Advancement Commission Act, a response to the 2017 Uluru Statement from the Heart. This statement represented a national Indigenous consensus seeking a voice in the Australian Constitution, which was ultimately rejected and dismissed by federal parliament. However, Victoria has made progressive strides, becoming the first jurisdiction in Australia to pass legislation towards a treaty.

The project explores the infrastructure needed over time for the uncertain process of negotiating a treaty between the First Peoples’ Assembly of Victoria and the Victorian Parliament within a modern context. It adheres to the objectives of the Victorian Treaty Commission while considering its implications within a broader political framework, all while operating within the constraints of a Commonwealth democratic system.

This represents the first time in Australian history that our nation collectively recognises and acknowledges Indigenous sovereignty within our Constitution. This highlights one of the many flaws of discrimination embedded in Australia’s constitutional framework. The architecture of this project seeks to embody the challenge and ongoing negotiation of law in establishing a treaty, paralleling the architecture of Parliament.

Titled The Carlton National Assembly, the project asserts a national condition within a local context, positioning architecture as a tool to substantiate the recognition of Aboriginal sovereignty across Australia.

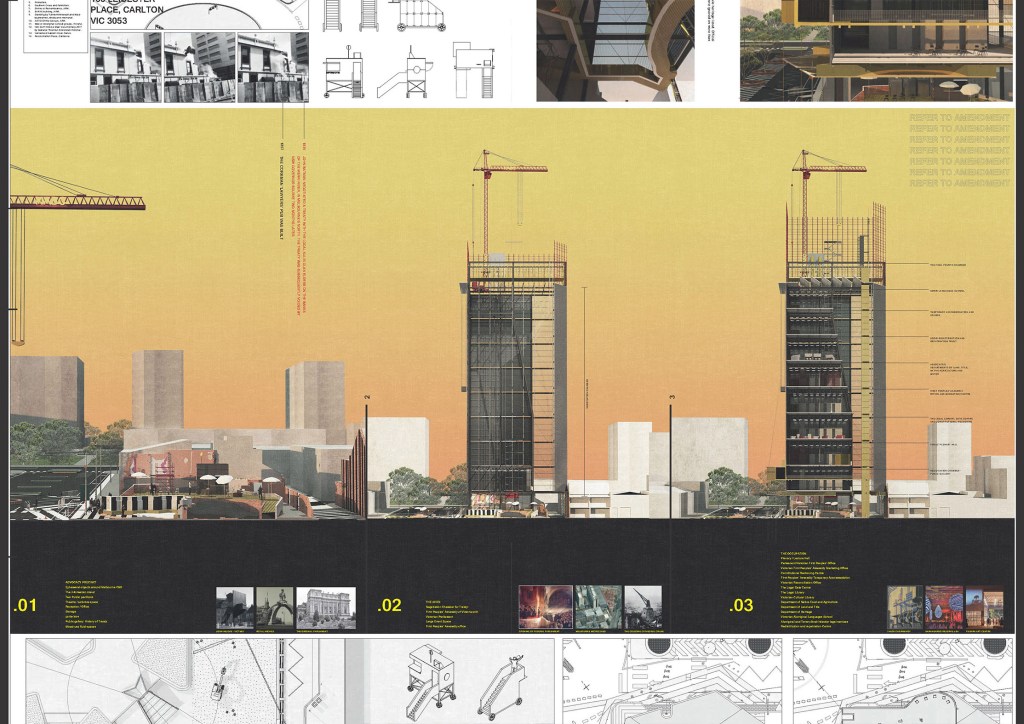

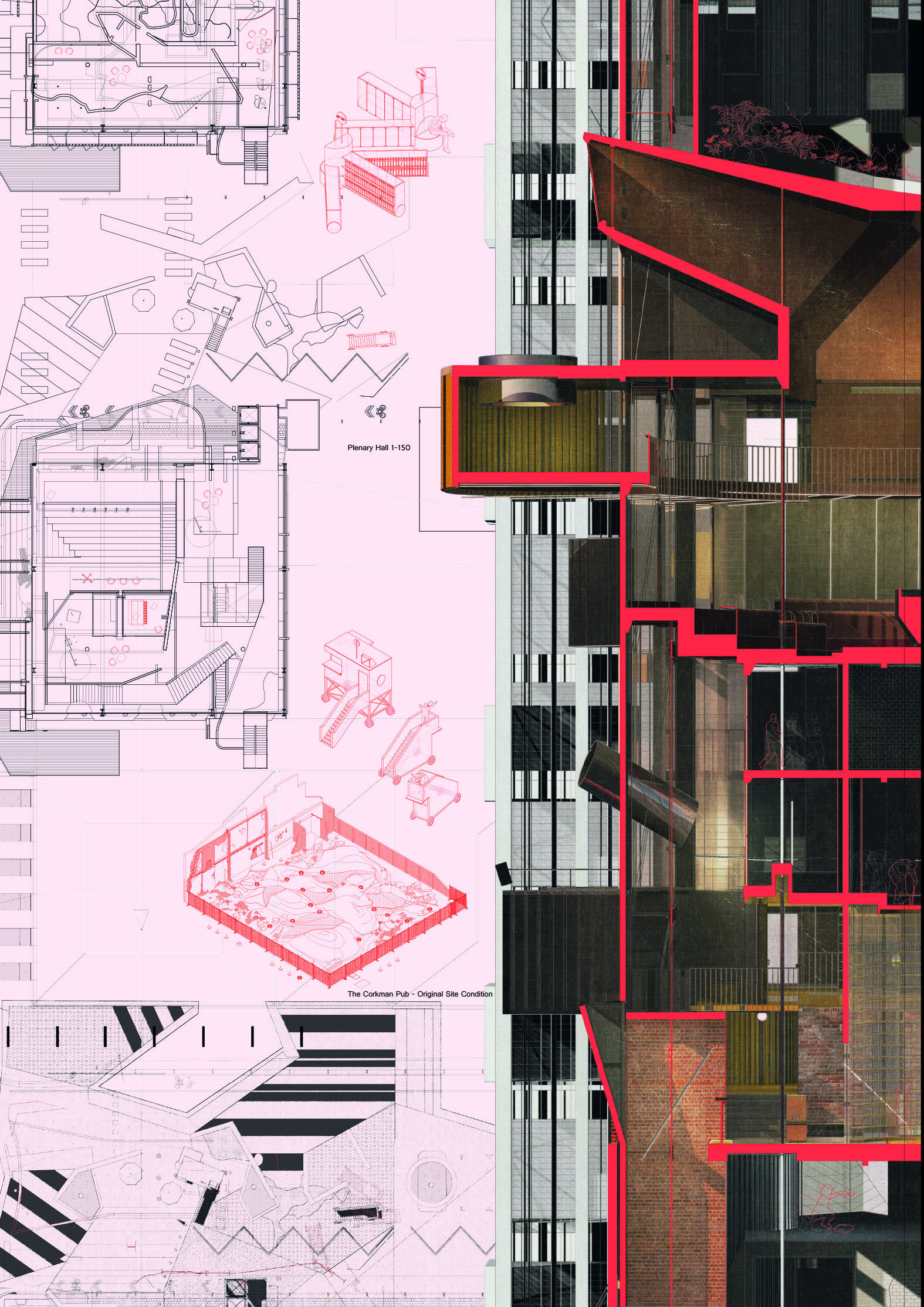

The site of the project is situated just down the road from the current Victorian Treaty Office in Carlton. It occupies a prominent political axis alongside the Shrine of Remembrance and the William Barak Building on Swanston Street. The first treaty drafted by John Batman upon the colonisation of Melbourne was also prepared in North Melbourne but was ultimately rejected by the NSW government. Shortly thereafter, the Corkman Pub was built in 1858 and became a local meeting place for lawyers. Today, the site is marked by a derelict pile of ruins, remnants of one of Melbourne’s oldest colonial pubs. This site embodies the insolvency of the law and prompts reflection on the value we place on our colonial histories. It stands as a significant provocation in its unique historical condition and is conceived as a monument.

Although located on the fringe, the project has a meaningful civic impact within the CBD, given its vantage point on Swanston Street. This led to the decision to incorporate a tower within the compact site while maintaining a scale relative to the surrounding evolving context.

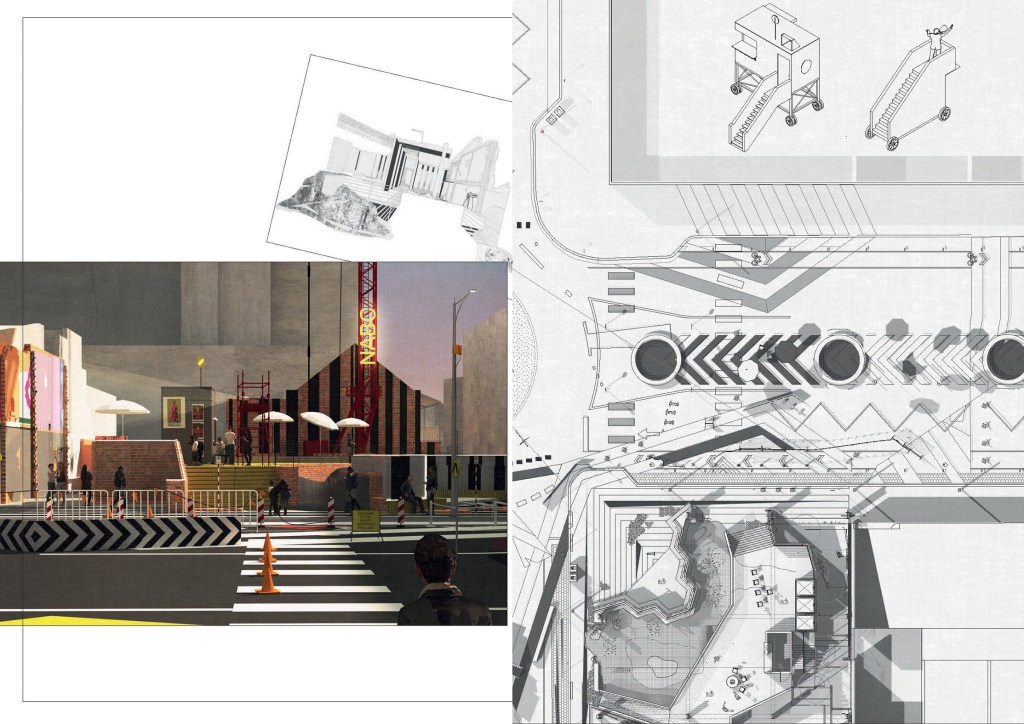

The project’s initial phase focuses on solidifying the ruin rather than rebuilding it. The site becomes a focal point for the architecture to establish itself within the larger precinct of Melbourne. The project begins with a series of small-scale, informal objects that reclaim land across the city, adjacent to significant sites such as Parliament House, the Royal Exhibition Building, and Batman’s Hill.

Parliament House is constructed on the site of the traditional ceremonial ground and meeting place for the five Aboriginal tribes of the Port Phillip region, known as the Kulin Nation. Yet, there remains minimal inclusion of Aboriginal voices in Parliament.

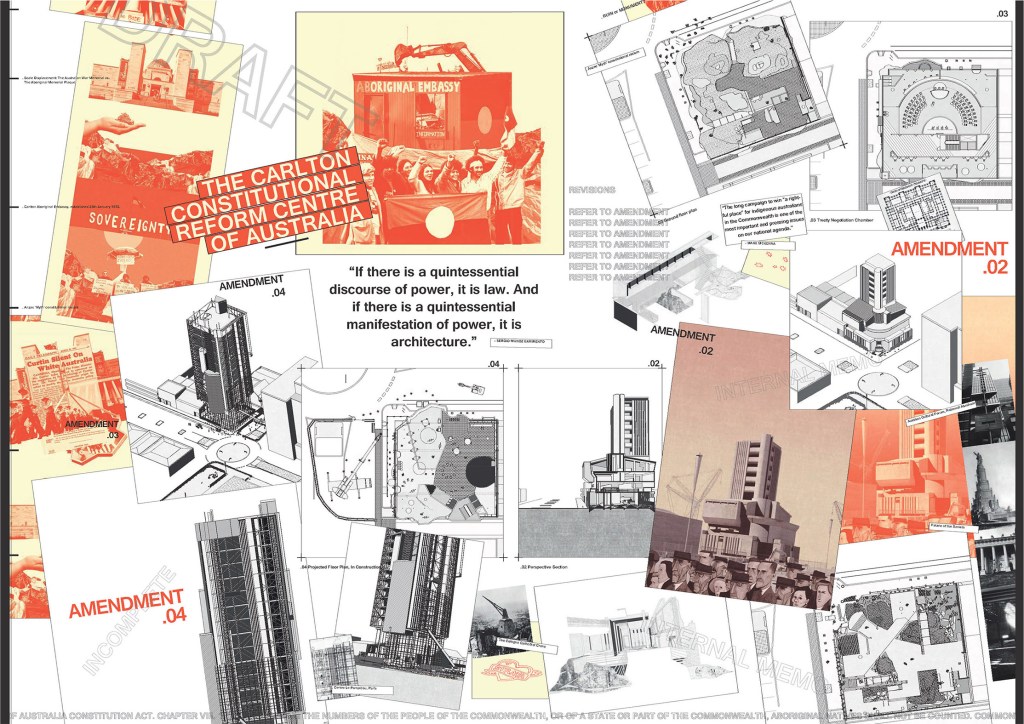

The project is intertwined with the narrative of establishing a treaty through the ongoing negotiation between two sovereign parties. This concept is explored in the design of the building over time, paralleling the Victorian democratic process. The final outcome remains uncertain and is only revealed through the continuous occupation and re-occupation of the architecture at various stages of its development. The project reflects the ongoing processes of fossilisation, erasure, amendment, and extension of architecture over different periods of the building’s occupation. The ultimate form of the project is anticipated to emerge from this dynamic process. Each new addition must negotiate with the existing conditions. In an academic context, achieving this outcome involves critiquing, amending, and fossilising previous building iterations. Spatially, this is reflected in the shifting of floor plates, spatial misalignments, adjustments to light, and the adaptation of programmes to meet evolving requirements.

This ongoing process can be summarised through three major phases of the project at different points in time: The Treaty Advocacy Precinct, The Shed, and The Carlton National Assembly, which together form the final architectural outcome.

The Advocacy Precinct began with the preservation of the Corkman ruin. It creates a public space, an unintended monument, and a mixed-use pavilion that anchors the site within the scale of the city. The informal objects that define the precinct draw inspiration from the political activist group that established the Aboriginal Tent Embassy on public land next to Parliament House in Canberra in the 1970s. This long-term occupation granted the group legal rights to the land.

The Aboriginal Tent Embassy is a significant example of collective activism, highlighting that community needs are not always met by the government. It exemplifies a politics of ‘re-occupation’, demonstrating a philosophy of land ownership through informal, ad hoc spatial occupation that endured for decades.

The objects in this precinct are strategies by which the project reclaims space beyond the colonial boundaries and defines a new territory within the city. This approach establishes a framework to challenge the everyday public realm and emphasises the political aspirations of the project, focusing on the collective.

The second strategy involves adopting construction language and coded ground markings to integrate the new condition with the surrounding context, effectively challenging the authority imposed on the built environment. This is most evident in the site plan, which highlights the slippages of occupation beyond the prescribed site boundary.

The project’s second phase began with an act of premature gratification, where the scale and impact of the entire project were established through the construction of The Shed. This structure was intended to represent the density of the program it would accommodate, driven by the urgency of establishing the treaty. The procurement model underscores a profound sense of urgency, as architecture is often constrained by economic limitations and lack of full government support. The Shed plays a crucial role in providing substance to this fragile pursuit.

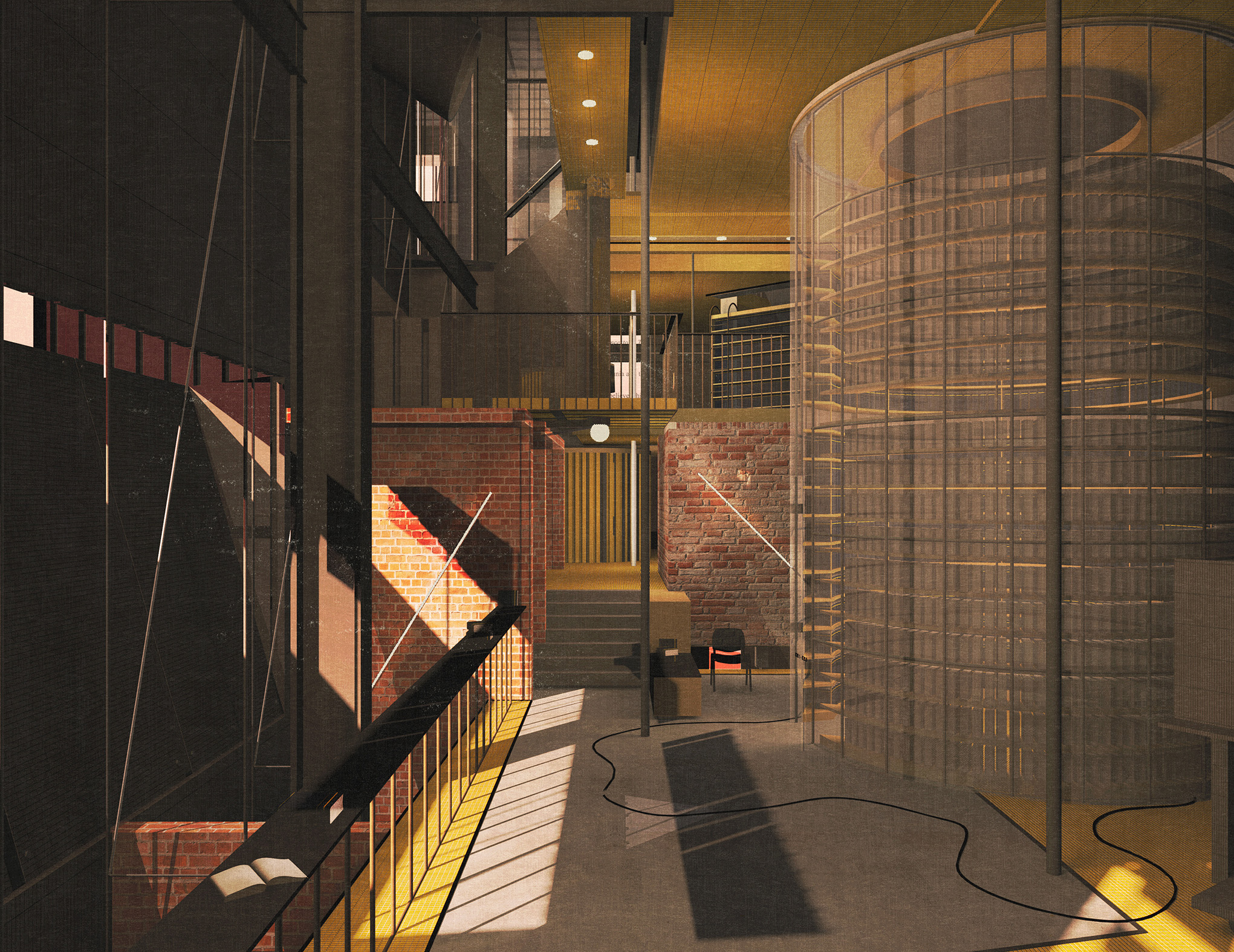

The condition of The Shed is then fossilised into the architecture, forming a layer that is negotiated with future additions to the program. More formalised functions are introduced, becoming integrated into the façade. The remnant of this condition is evident in the façade’s skin, where negotiations with light and embedded programs create slippages and protrusions, resulting in nuanced lighting conditions within the interior spaces.

The architectural program aligns with the repercussions of establishing a treaty and relates to the functions of Parliament. The design aims to balance prescriptive space with adaptability and diversity, accommodating both immediate and future needs.

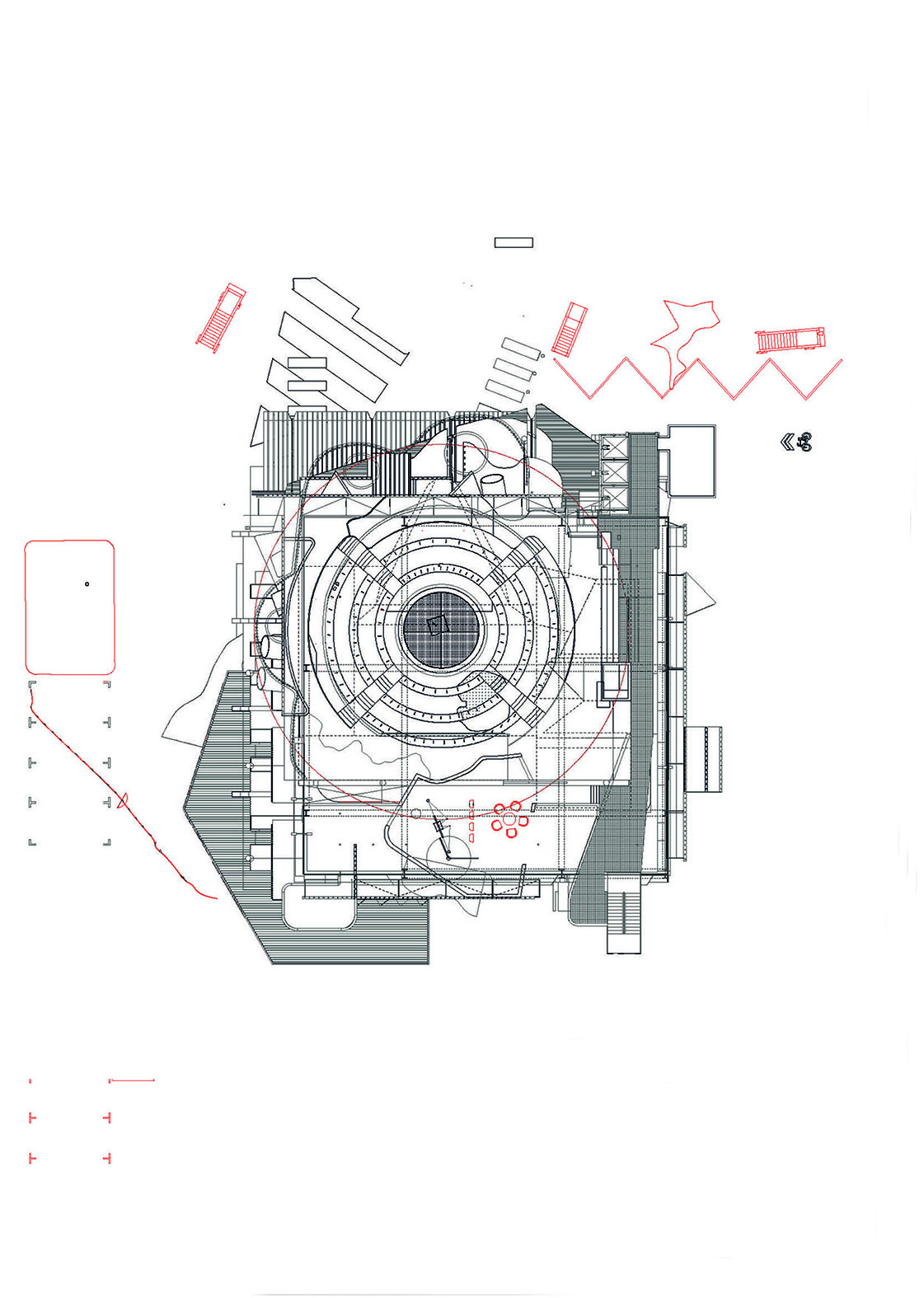

The key public functions in the large-scale proposal include the public pavilion at ground level, the Plenary Hall or formalised advocacy precinct, the Constitutional Library, and the final Negotiation Chamber.

The approach offers a satirical critique of the colonial Commonwealth-style systems that shape our built environment and politics. The formal architecture of Parliament has been studied to inform the project’s deconstruction of Melbourne and Canberra’s static, ordered, and classical parliamentary expressions. This has been translated into the project through various conditions.

XML’s study of the United Nations’ parliamentary designs highlights how senate chambers have remained static across five distinct typologies, despite contemporary shifts.

The essence of the treaty is to ensure all Indigenous clans within Victoria are heard. Currently, 12 of the 38 language groups in Victoria are not legally recognised within the Australian legal framework, raising concerns about inclusivity in the process. The design aims to reassert its function within the public realm.

The final Negotiation Chamber is designed to accommodate the 38 clan groups in Victoria, with 76 allocated seats for both genders. The chamber deconstructs the traditional distribution of power in Australian ‘horseshoe’ senate chambers, challenging the Commonwealth-style hierarchical democracy. The colour scheme of the Negotiation Chamber echoes that of the Senate in Parliament.

Disruption of stasis and order is achieved by providing an informal, adaptable planning style that accommodates disagreement and chaos on an equally distributed playing field.

A public circulation gallery offers an alternative route to the lift and stair core, wrapping around key public programs and emphasising the role of the collective. The galleries, being the most transparent public components, prominently feature on the façade, as seen in the yellow protrusions.

The Library serves as a space for re-telling past histories and future narratives, representing the diversity of language groups and cultures within Victoria. It facilitates reconnection, learning, and interrogation of Australia’s history.

The Plenary Hall extends the treaty advocacy precinct, featuring a theatre and spaces for diverse assemblies. The gallery on the façade, initially occupied as the negotiation chamber, has been repurposed as a public gallery and intimate working spaces adjacent to the theatre.

The spaces are designed to accommodate specific functions while focusing on spatial fluidity and adaptability to meet varying programmatic needs.

The core and circulation strategy follows the approach of Richard Rogers’s tower proposals, positioning the toilets, stairs, and lift core outside the building’s floor plate to optimise space within the tight footprint.

The floor plans of the programs reflect the narrative of continuous architectural negotiation through time, representing an archaeological condition where architecture is fixed, re-written, and coming into being.

The project examines the dual role of architecture in both challenging and embodying power, and the resulting social and cultural impacts it can have. Architecture has the power to both affirm and contest authority. In this instance, the design of Parliament has been questioned and adapted to substantiate the sovereignty of Aboriginal Victorians. This adaptation reflects a certain frustration with the narrative, underscoring the urgency of progressing towards a treaty amidst a reality where the government allocates $50 million towards a Botany Bay redevelopment instead of prioritising treaties with Australia’s First Nations peoples.

The architecture is staged as a series of infrastructures that immediately present a solution. Negotiation occurs post-factum. Each stage involves re-evaluation, amendment, and adaptation of conclusions, recognising our fallibility, our obligation to persist, and the capacity of architecture to commit to the community it serves.