In the Blood

RMIT University Master of Architecture Graduate Project 2019

Supervisor: Michael Spooner

Awarded the Leon van Schaik 25th Anniversary Peer Assessed Major Project Award

Things I Mistake for a Bird on July 26.

Superman, a plane, probably a bigger bird for a smaller one. It is dusk, and warm.

Sounds of crickets chirping resonate/ like a dark haze of unknowing distance.

I look outwards from the porch of my family’s house, sitting on the corner of a cul-de-sac named Star Street and a longer winding road named Fonti, a white wrought iron fence cascades along the road and curves inwards, hugging a great big front yard and a red-green brick house formed with arches. It is a surprisingly Italian-styled house for where it is located; a small North-Eastern suburb in Sydney.

My parents tell me that the house we live in is built by our neighbour Joe, who we affectionately refer to as Uncle Joe; who first sold it to a Japanese couple, an Italian family, and then to us- a Chinese family of four. It is a house built with a painstaking love for banality. An ordinary house surrounded by intricately Good things: A wall of bright red Bougainvillea on the right, a bed of flowers in the front, and white cherry blossom trees in the front yard. It is my parent’s first house, and the spring after they moved in, I was born.

The one thing my mother loves especially is the lone Jacaranda tree which settles itself right in front of the house. Its leaves remind me of the poem Violets by Gwen Harwood; ‘the melting west is striped, like ice cream, while dusk surrenders pink, and white to blurring darkness.’

…

The tree hosting the family of magpies is not far from it. The umbrella that I carry with me is a golf umbrella; inconveniently large, equipped with springing mechanism and all. I walk home every day expecting the birds to swoop down on me, but they never do. It makes me wonder who would have won that fight, the group of territorial birds, or 10-year-old-me with the stick-thin arms and thick-rimmed glasses. They must have shown me mercy.

…

The number plate on our first family car, a metallic blue 1988 Honda Legend, reads E-L-I 2-8-6 in black text against yellow enamel.

It stands for the initials of the four of us: Eddie, Elsie, Eden and Emma. My mother never fails to remind me that she chose these numbers with intention. The numbers sound just like the phrase “it’s easy to be happy” in Cantonese. It is a refrain that we carry on with us through childhood, although perhaps it is only in retrospect that these half-truths became the most concrete.

…

My project starts out at Sydney, the city in which I was born, and ends in Melbourne, the city in which we are in as I make this presentation. It is a product of what I can only describe as self-indulgence.

“Is there really still a Sydney Melbourne rivalry” can only be answered by the number of times that I have been asked “So, which do you like better? Sydney or Melbourne?”

The case study of Sydney-Melbourne aims to speak to how we may see each other, and what it means for either city to accept my living there.

It is a chance to speak to how I see myself- always pursuing a provocation of the institution from the outside, while never quite shaking off the fear that I will not be seen as anything more than someone of first-generation blood attempting to become something else.

Perhaps it is an admittance that my love for provocation comes from a fear of being reduced to the same trope. A working burden of sensitivity to the words identity, immigration, and diversity. Or, of colour, yellow against white, white against black, black text against yellow enamel.

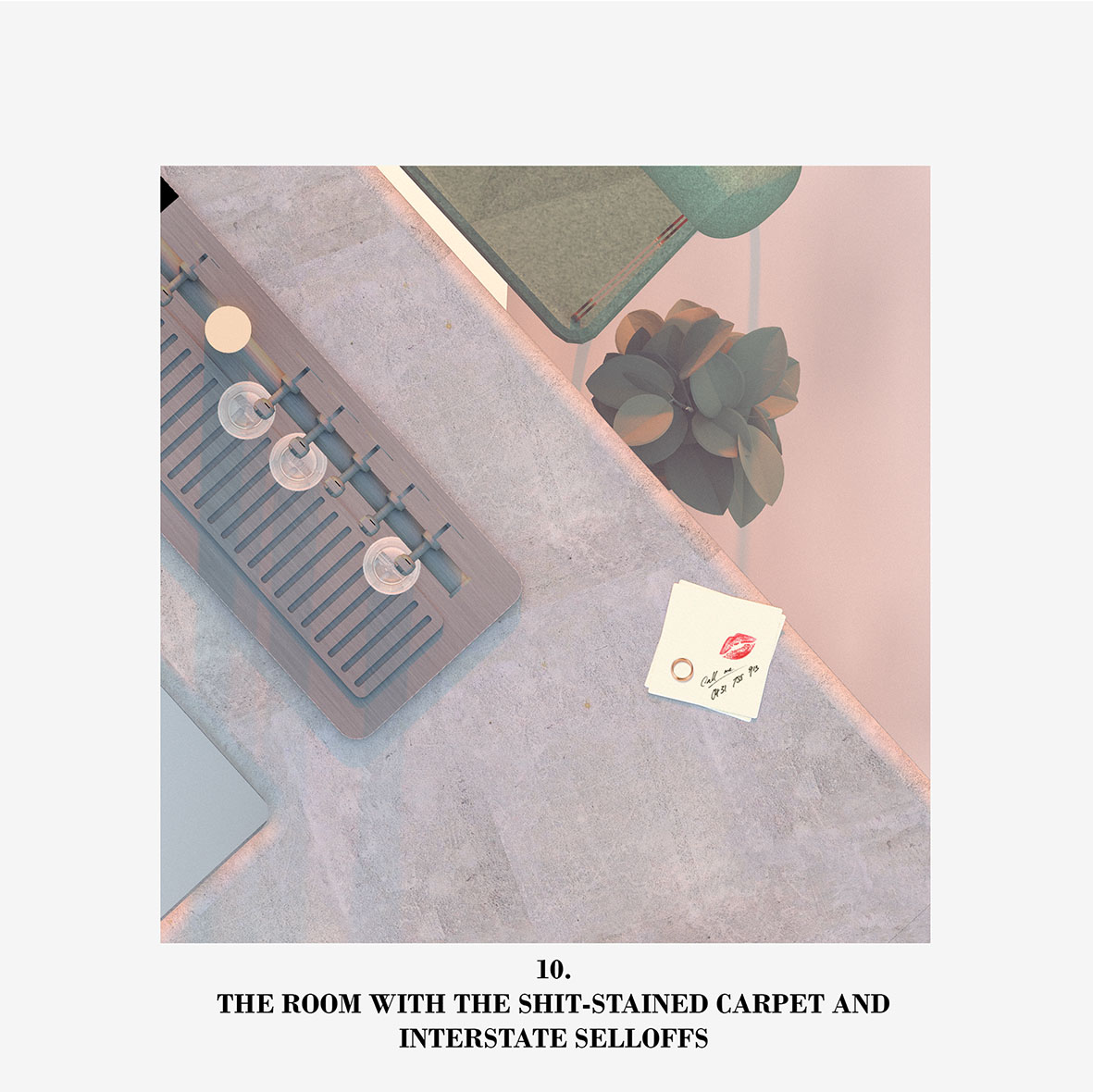

However, this project is not about guilt, penance, or the absolution of sins. It is not about the coming together of identity or the resolution of the Other. It is about fighting-off magpies, the AFL during trade week, and the lipstick you leave on her collar.

…

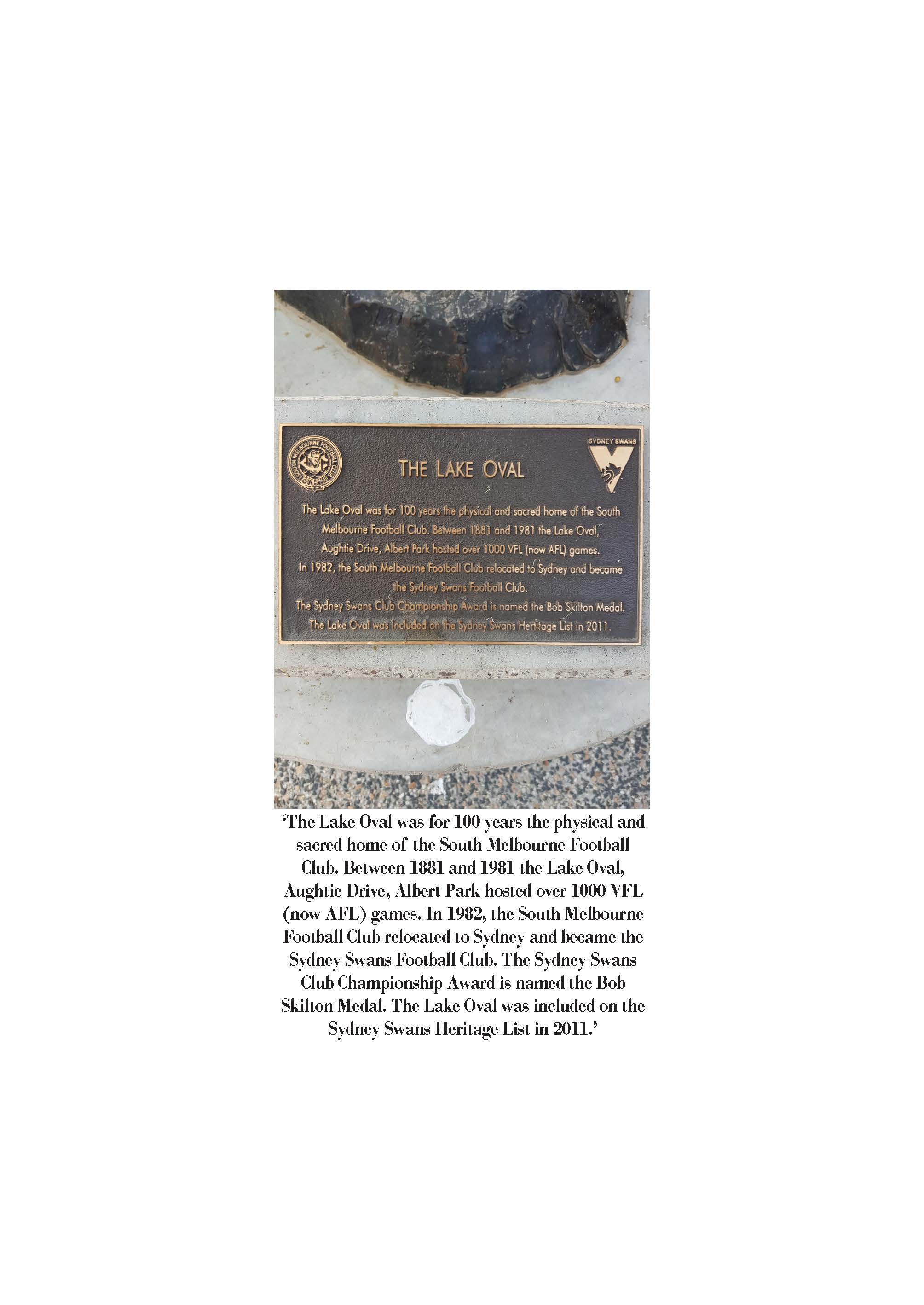

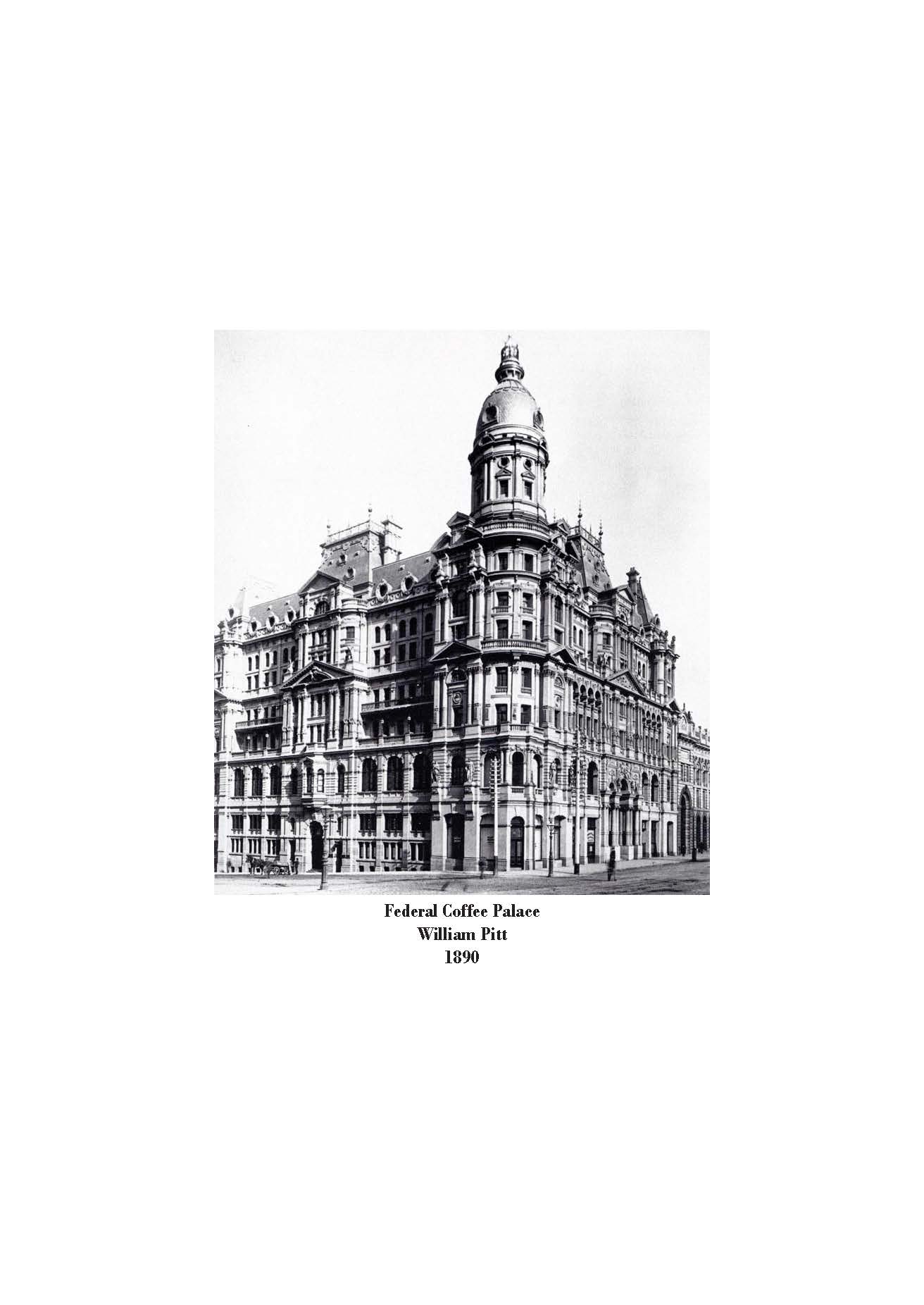

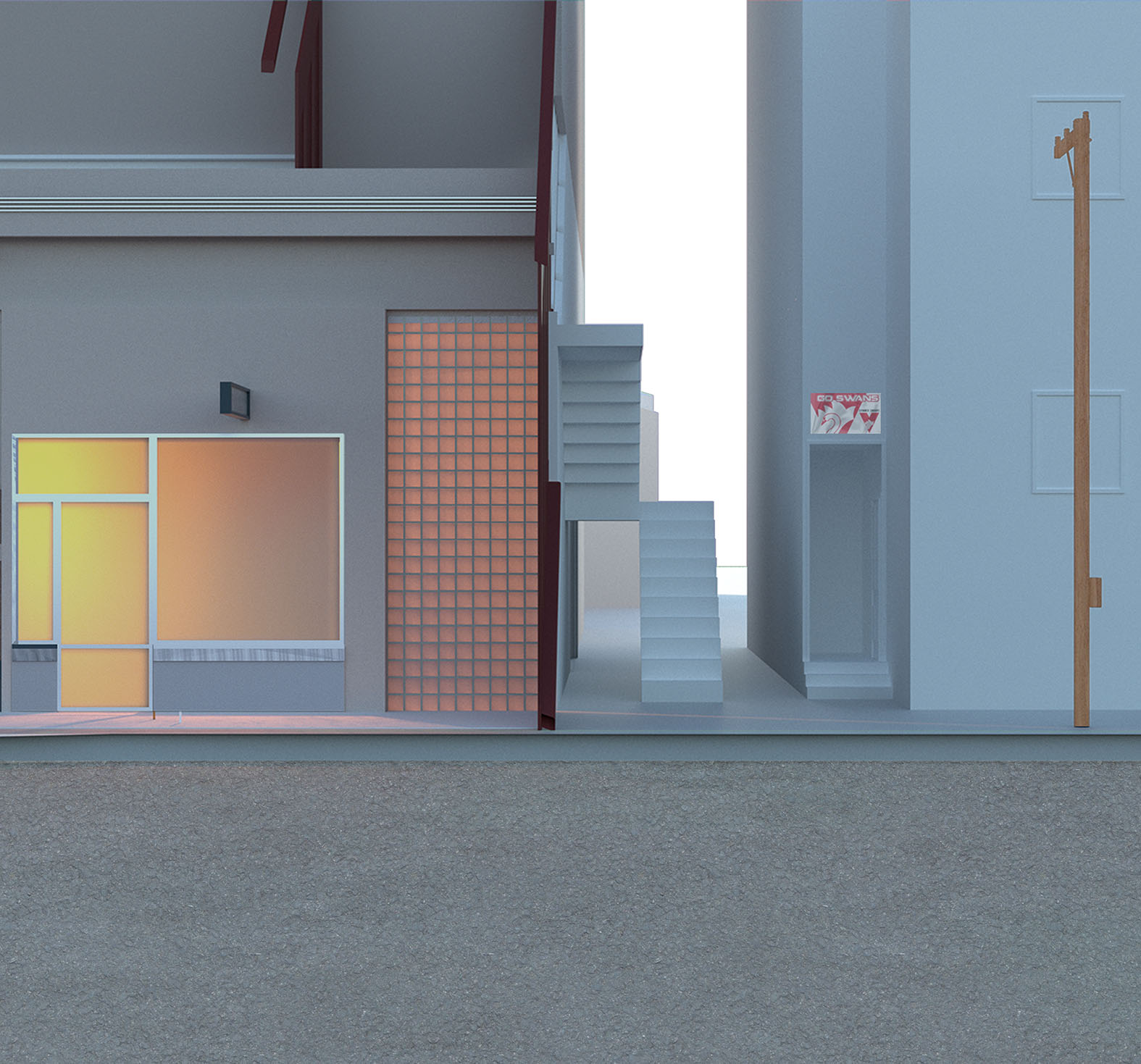

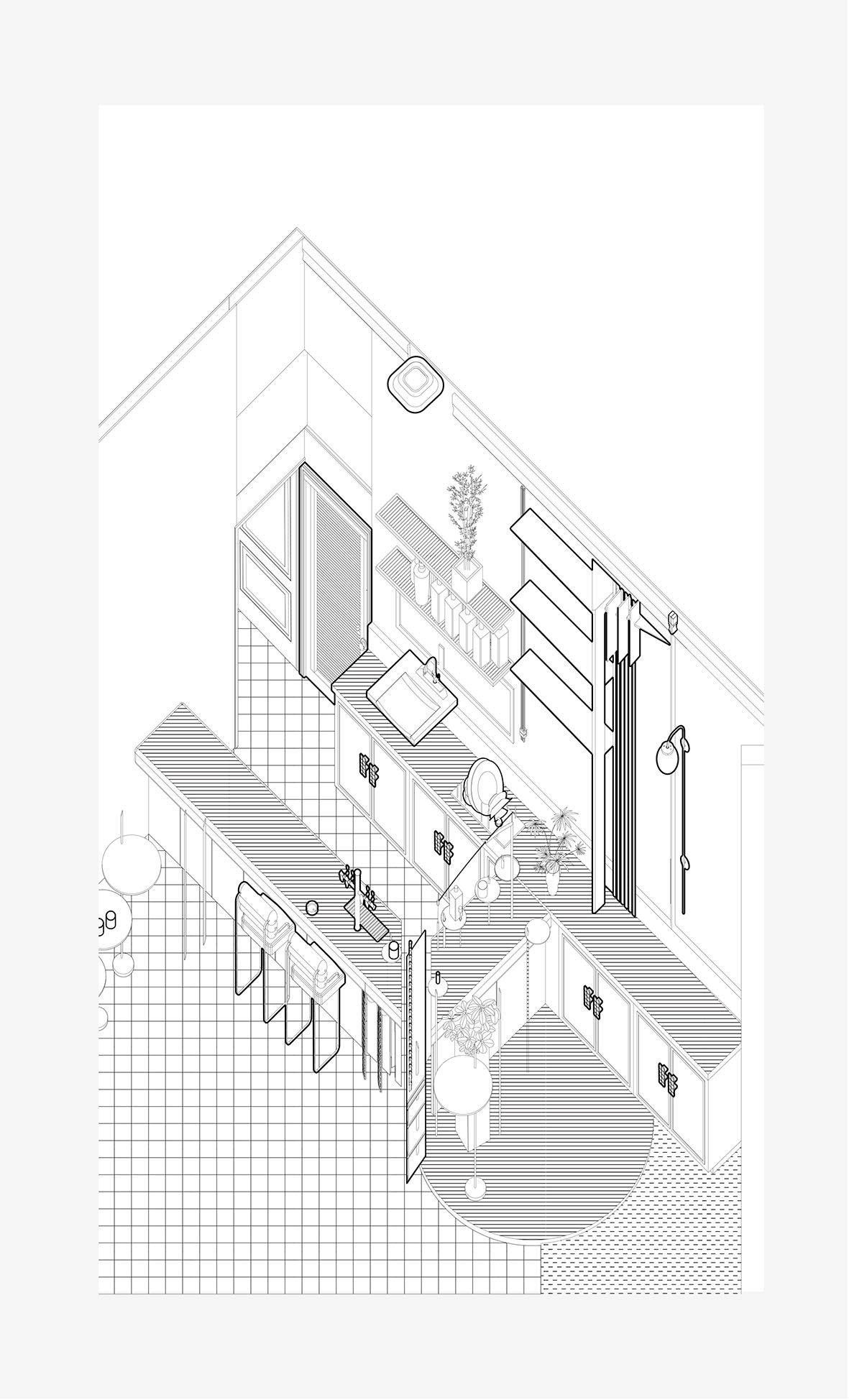

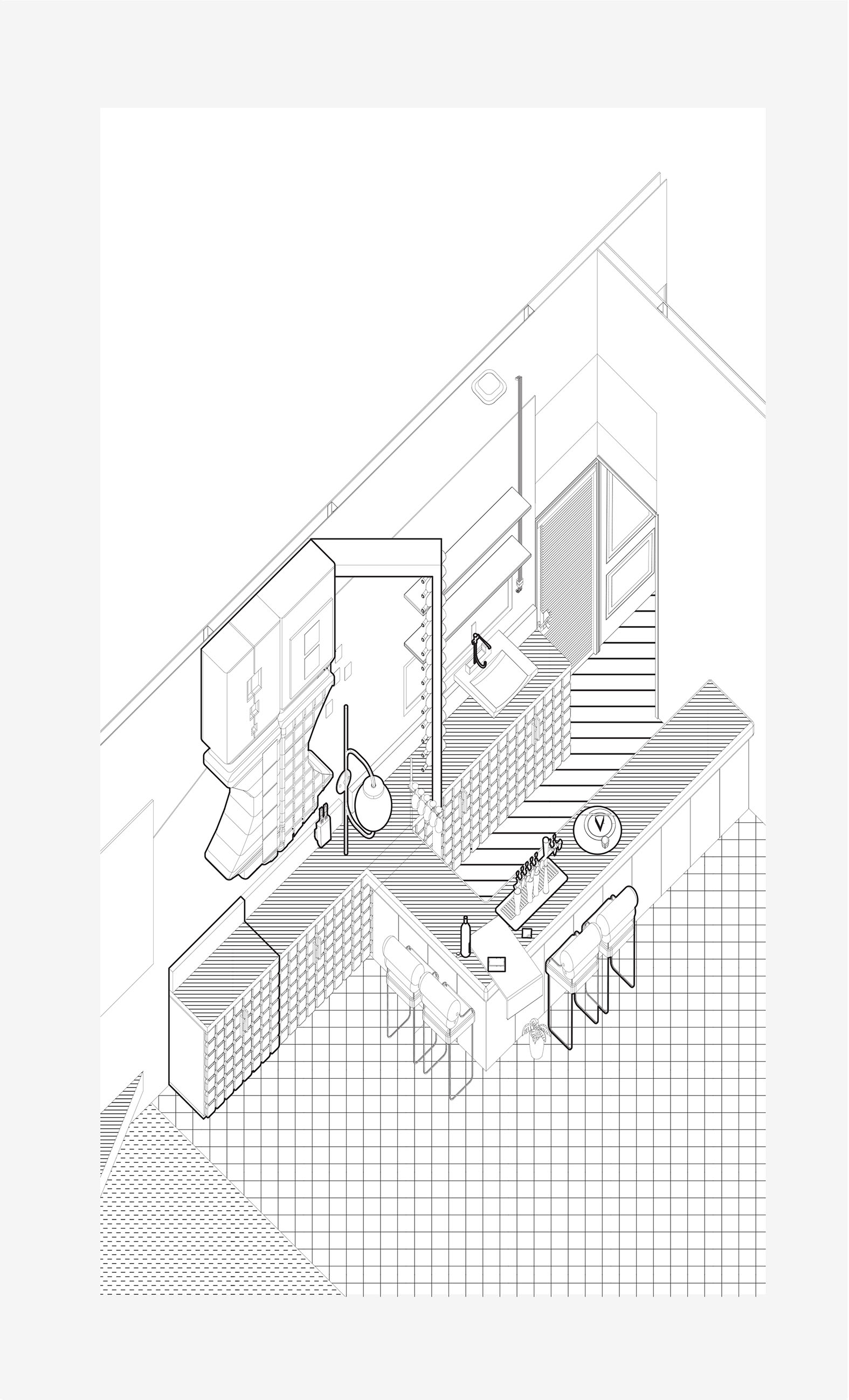

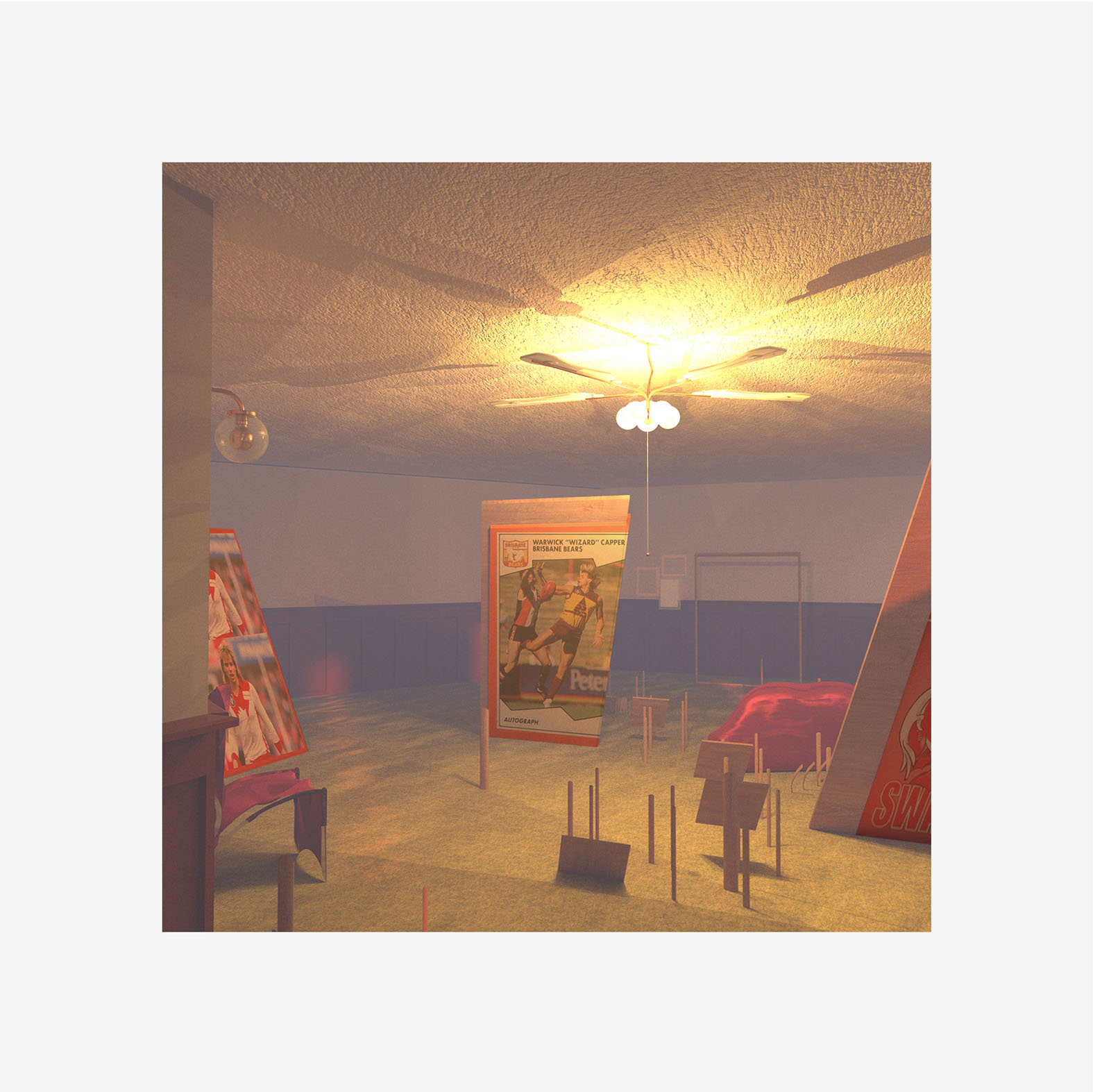

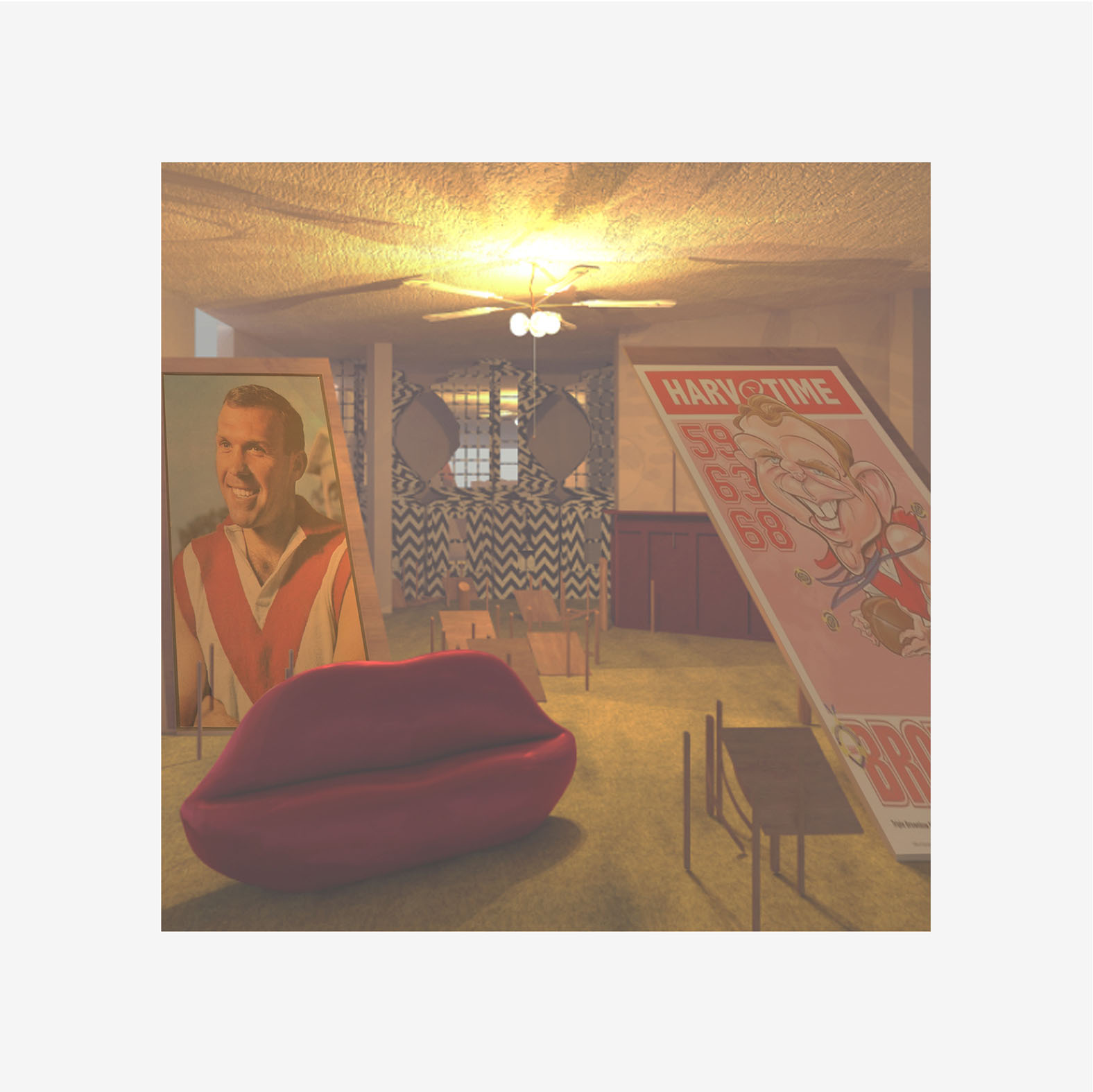

Situated on 2 Raglan street South Melbourne, the site of the Rising Sun Hotel is the home for Melbourne fans of the Sydney Swans. Adorned with red and white memorabilia, it is the closest Hotel to the original home ground of the once South Melbourne Swans.

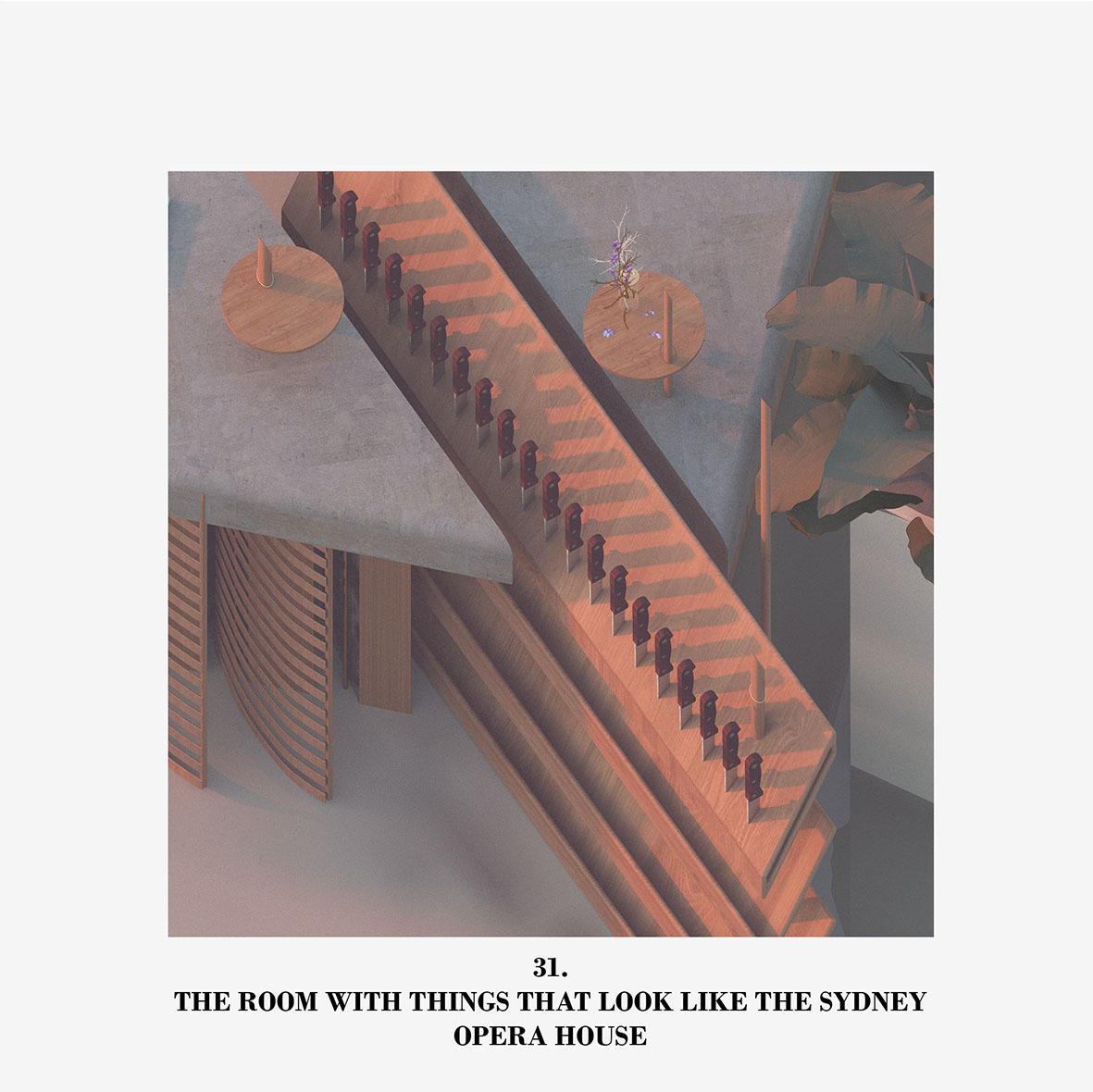

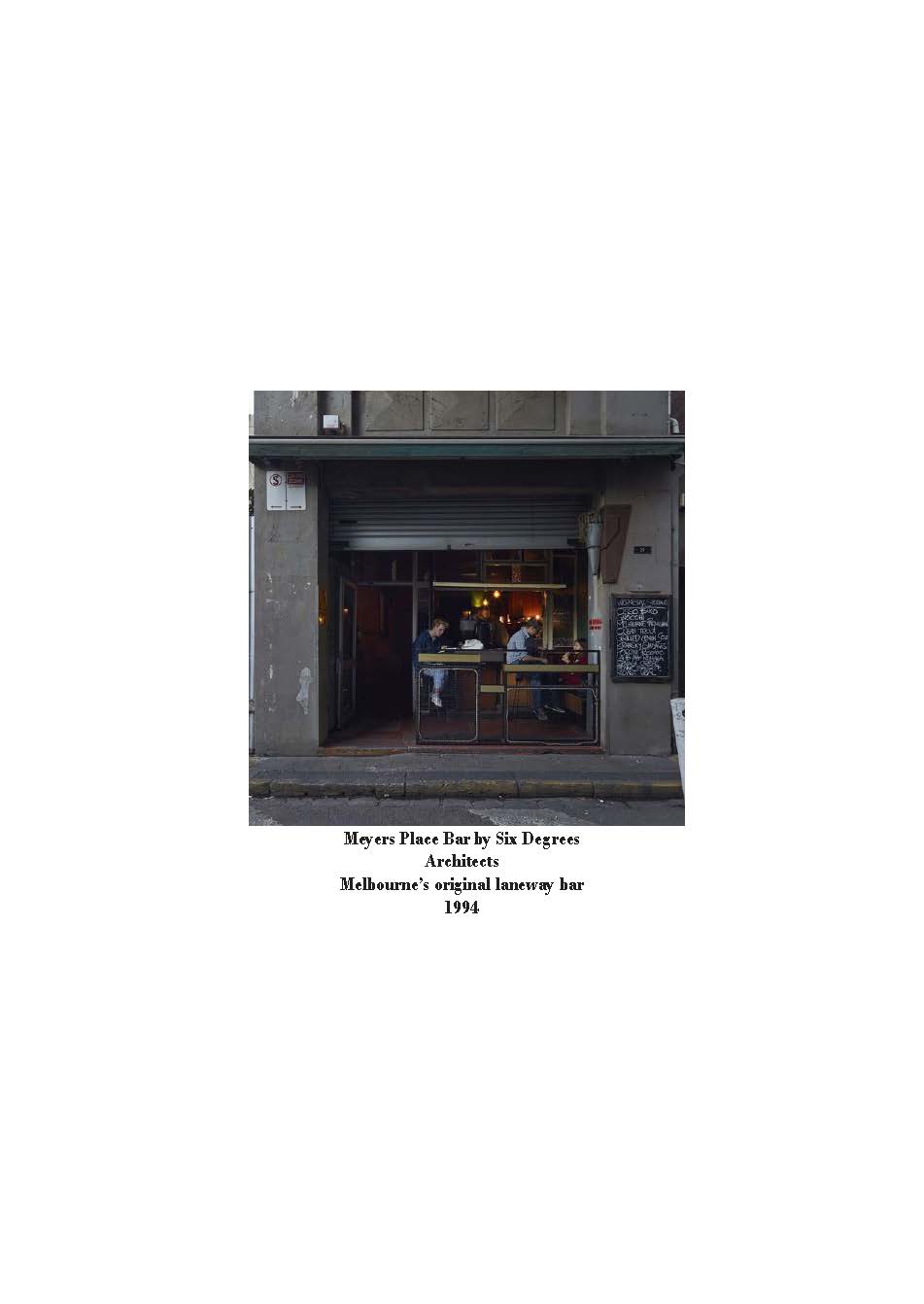

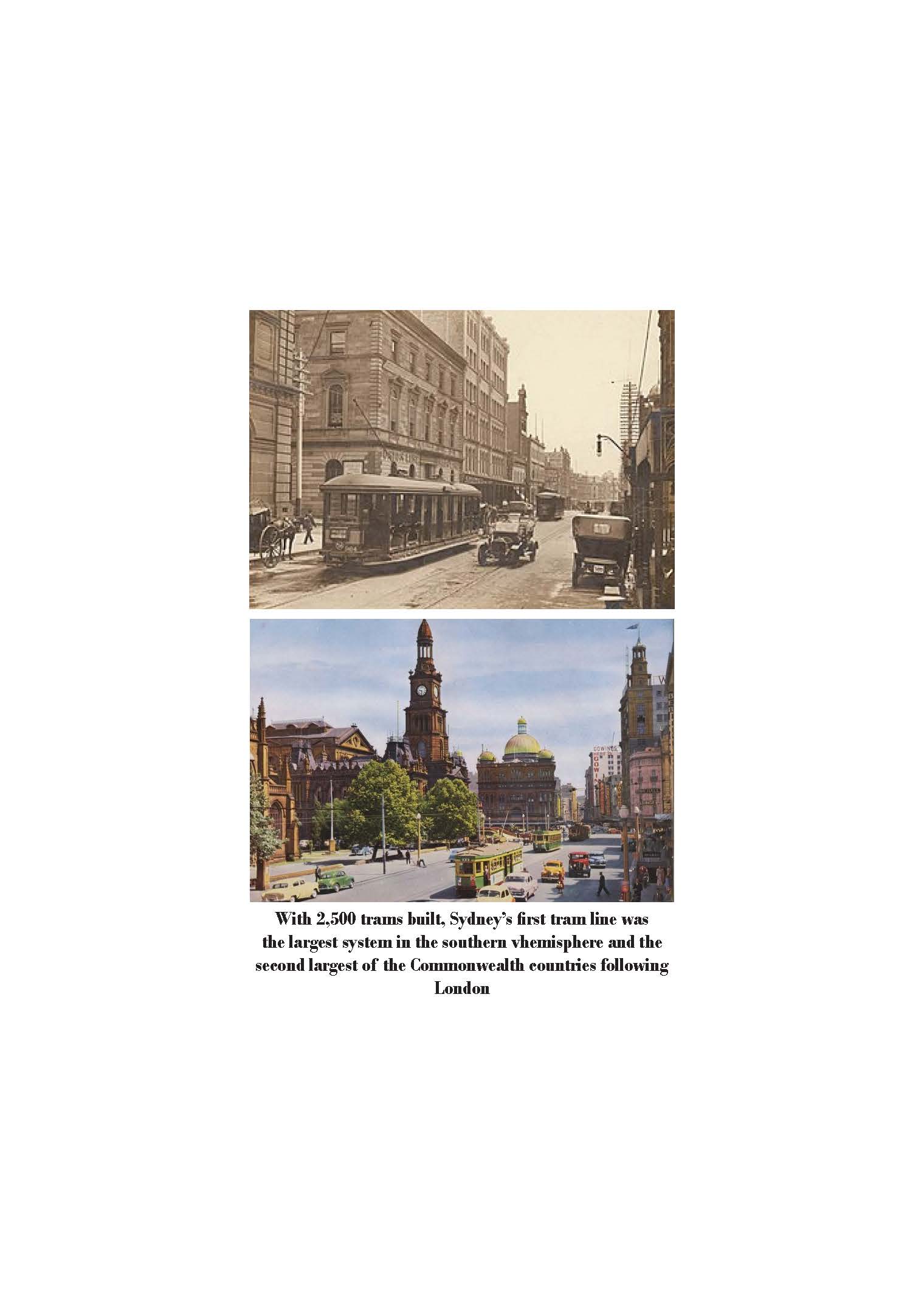

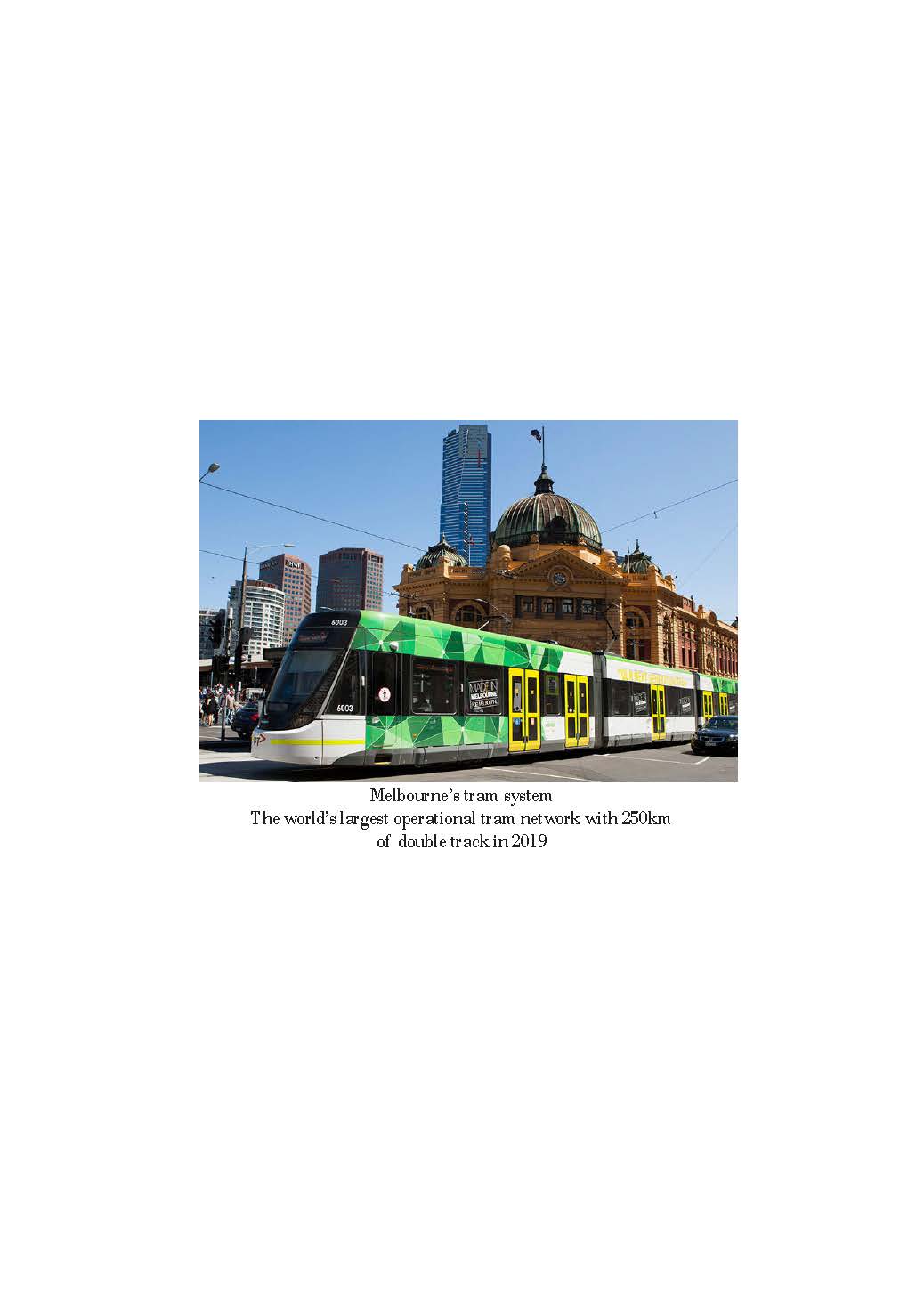

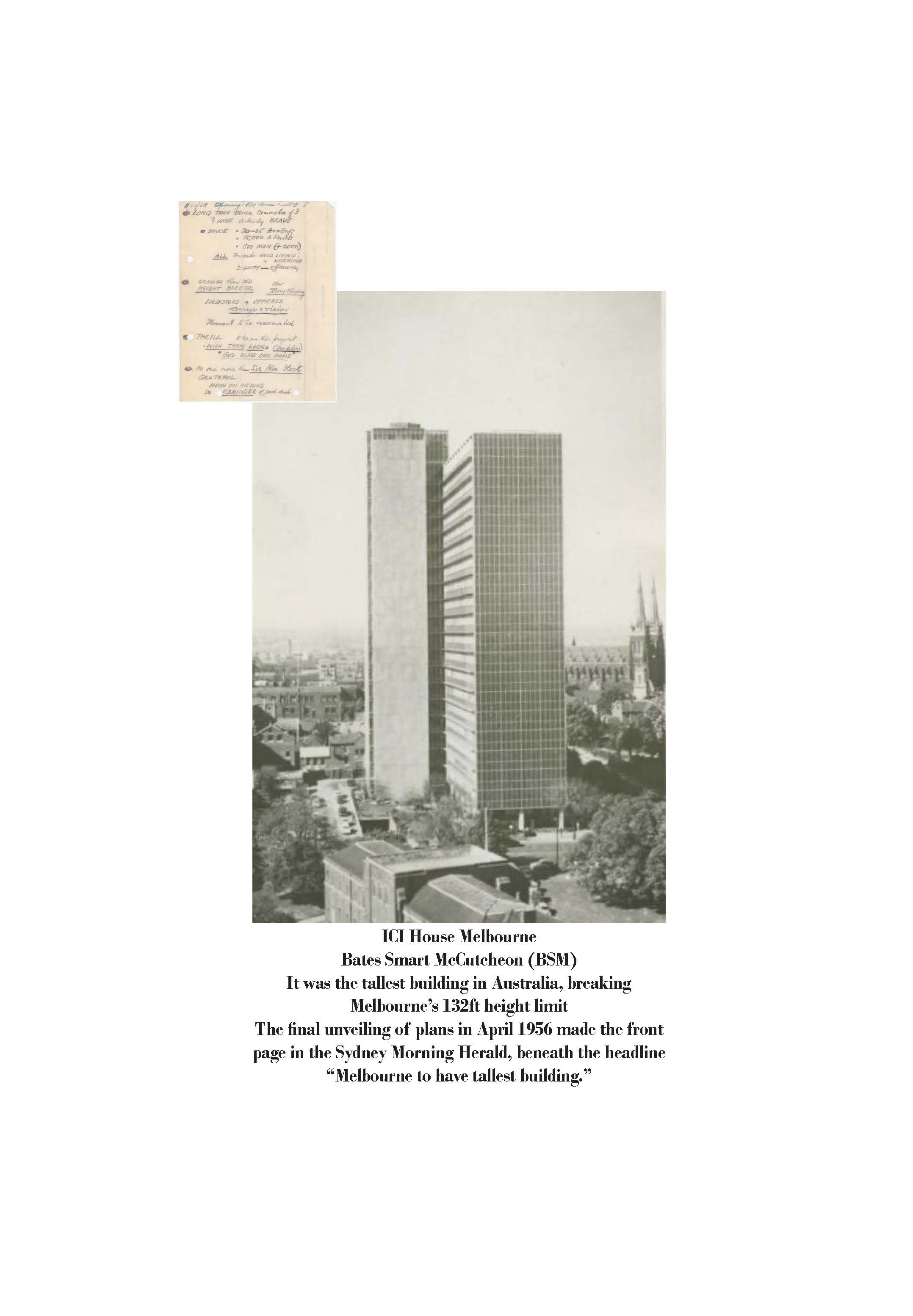

In distinguishing between Sydney and Melbourne, tropes are readily recalled. Of course, Sydney has the Sydney Opera house; Melbourne has its culture and hidden laneways. After all, ‘a rose is a rose is a rose’; saying the word Sydney brings up images of Sydney, Melbourne brings up images of Melbourne.

When it comes to city pride, people from Melbourne describe their city as cultural and fashionable; in contrast, people from Sydney see their city as beautiful and famous.

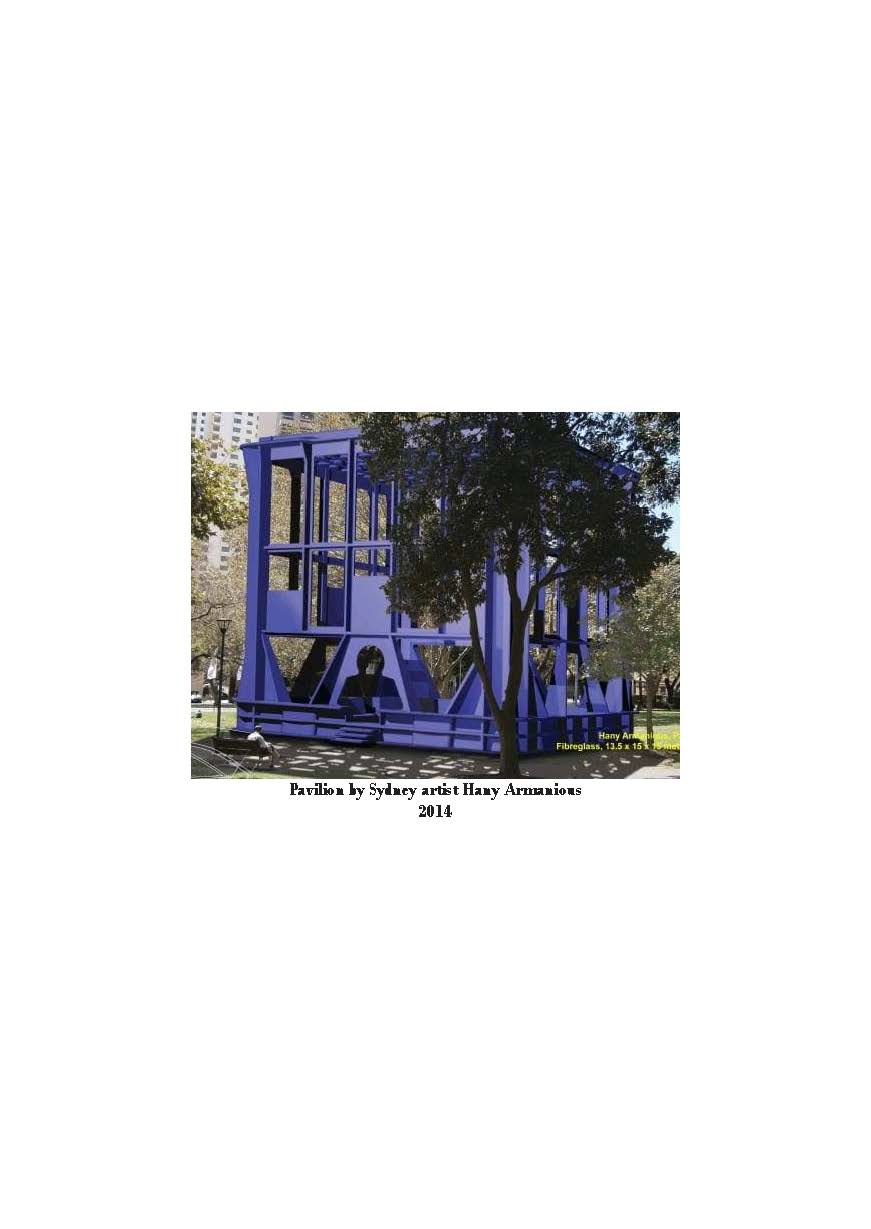

When it comes to creative expression, the art of John Olsen and John Brack are merely ontological remarks on the crisis of topography.

In sports culture, the rivalry can be only summarised by the Sydney FC’s chant to the tune of We Are Australian; which has all the same lyrics but ends with “I hate, you hate, we hate Victorians.”

The struggle to discern between the two cities exists in recent publications such as ‘Sydney, Melbourne: Reflections; and debates such as ‘Sydney versus Melbourne Ambiguities’ which only reveal the binomial Sydney-Melbourne as a continuing antagonistic repository for architectural anxieties.

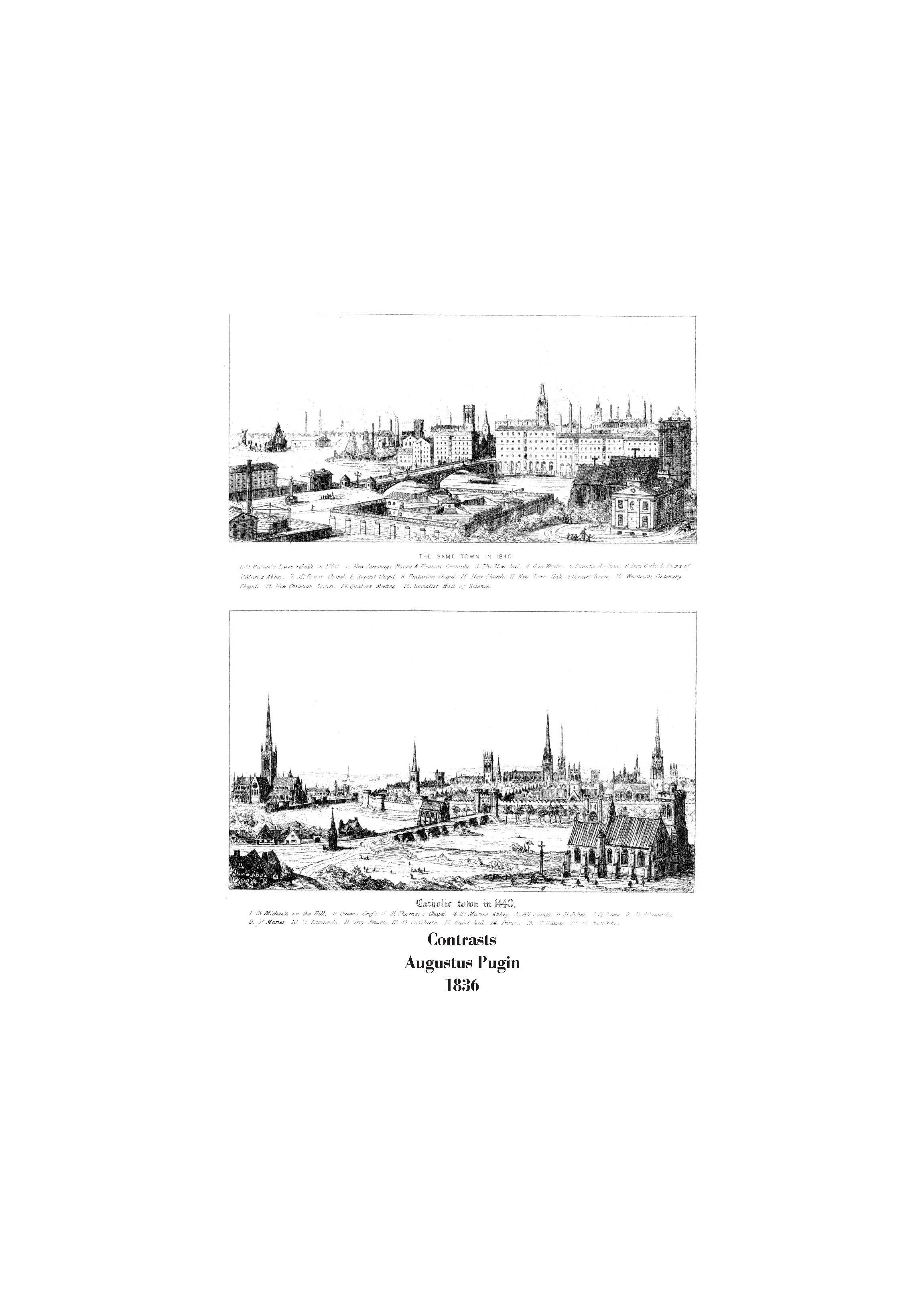

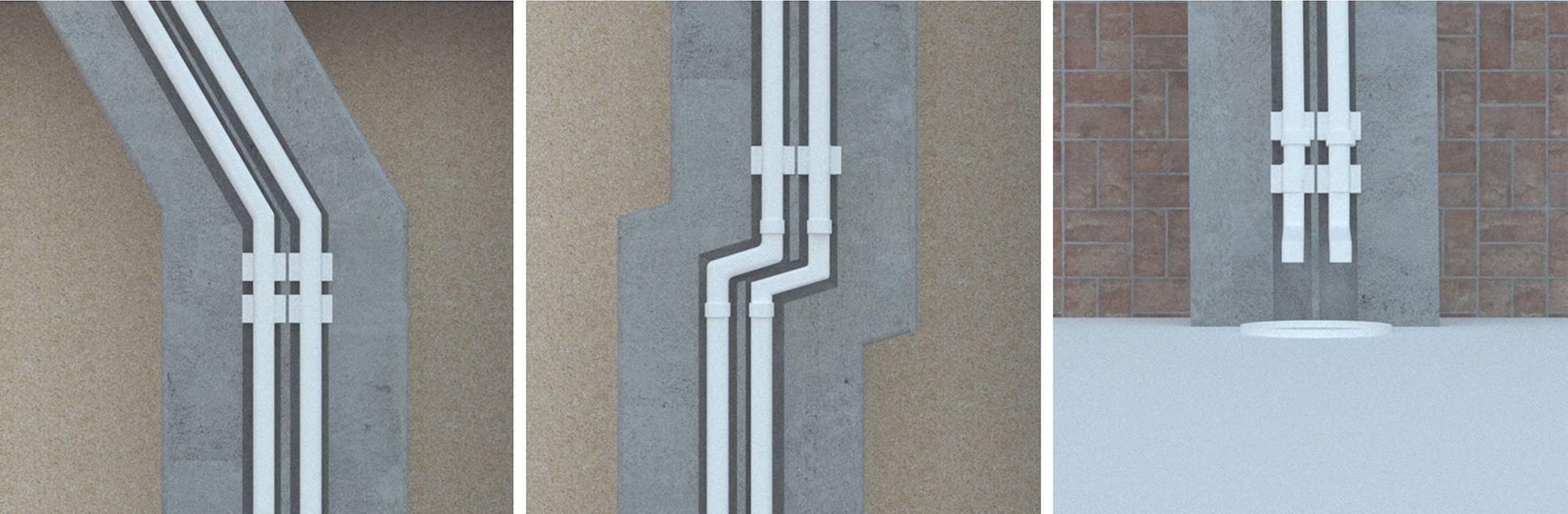

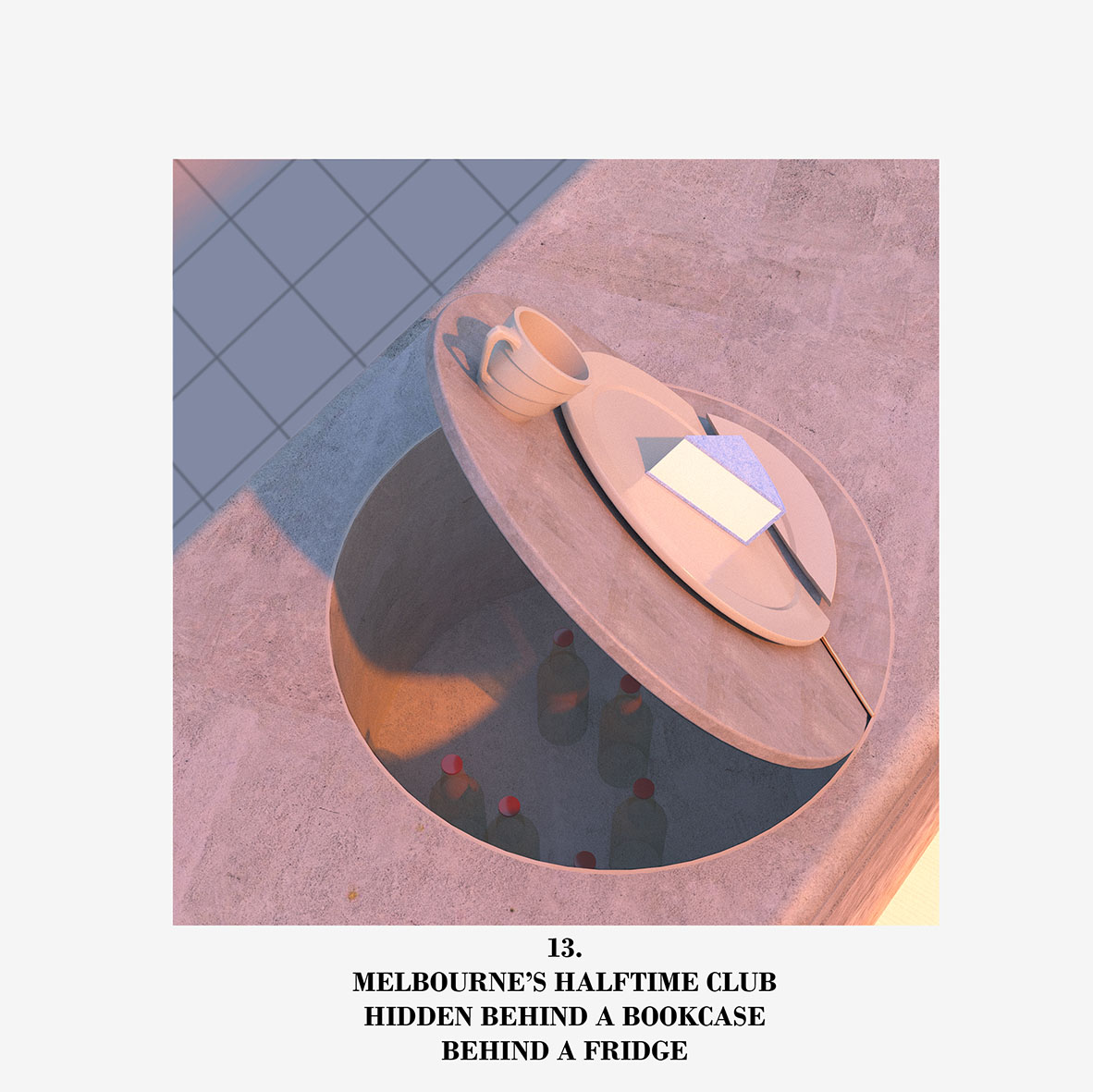

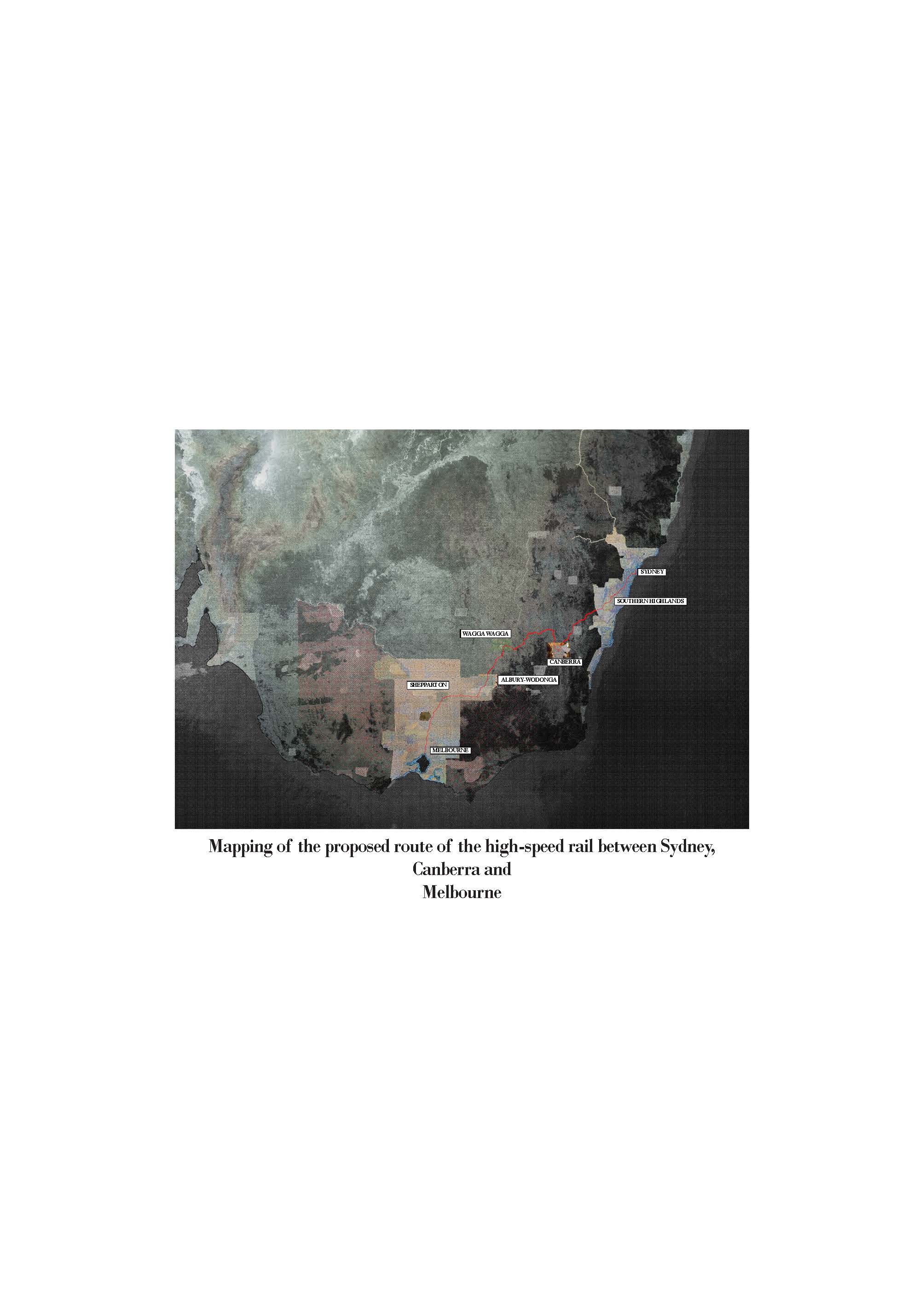

In determining what Sydney-Melbourne is, it is best to imagine the Sydney to Melbourne high speed rail. A partial myth which makes explicit both the fallacy of these truths while cementing them. Here, the ‘dark’ as a captivatingly modern term, where what is unseen can be modelled through light, acclaims itself to the technique of chiaroscuro, drawing reference to the modern presence of dark rooms, dark stores, and dark kitchens. In Windsor, the new Deliveroo Editions houses 25 dark kitchens with no seating or customers, behind the guise of a regular Thai restaurant. It exists only as a form of sfumato.

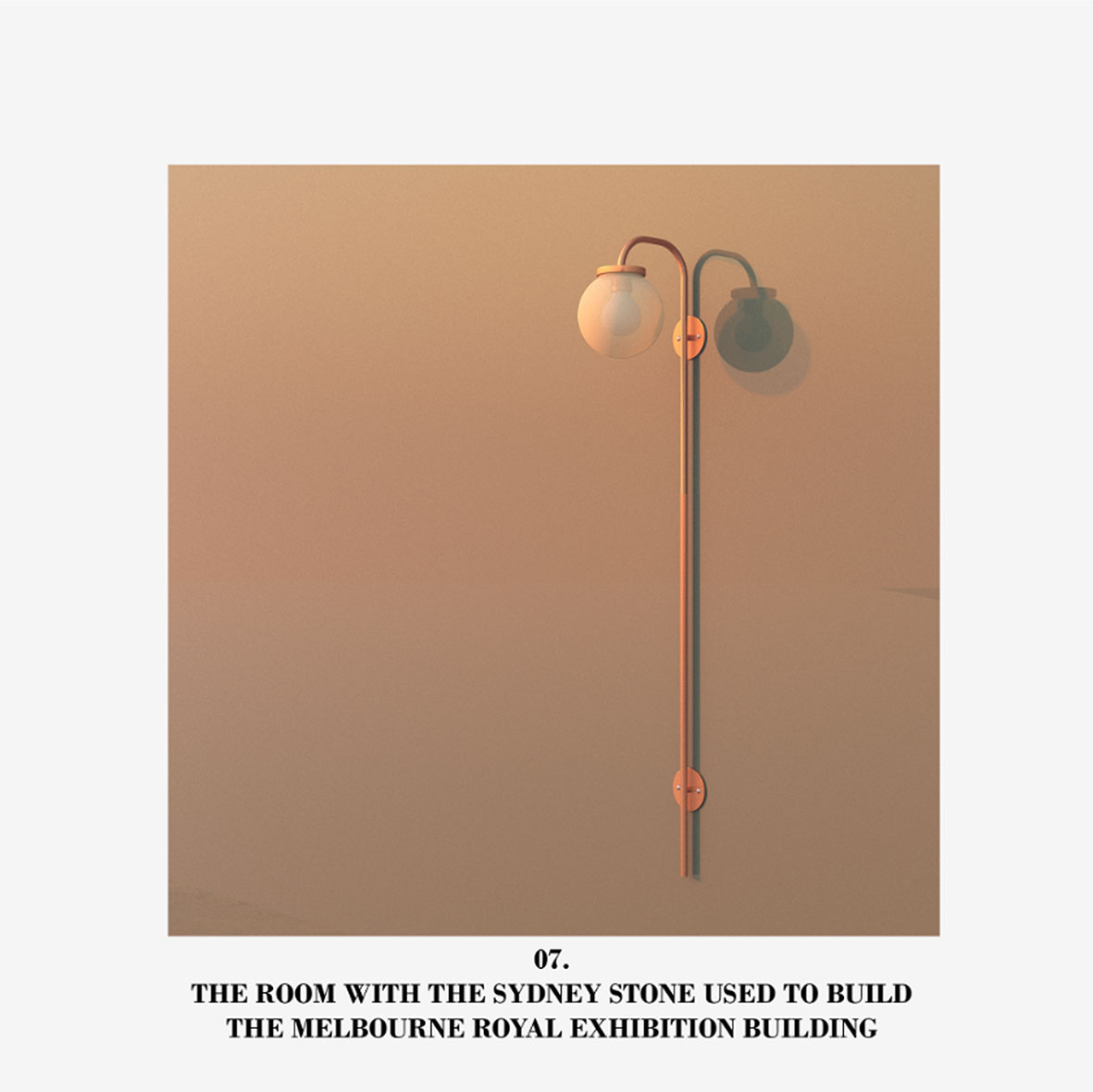

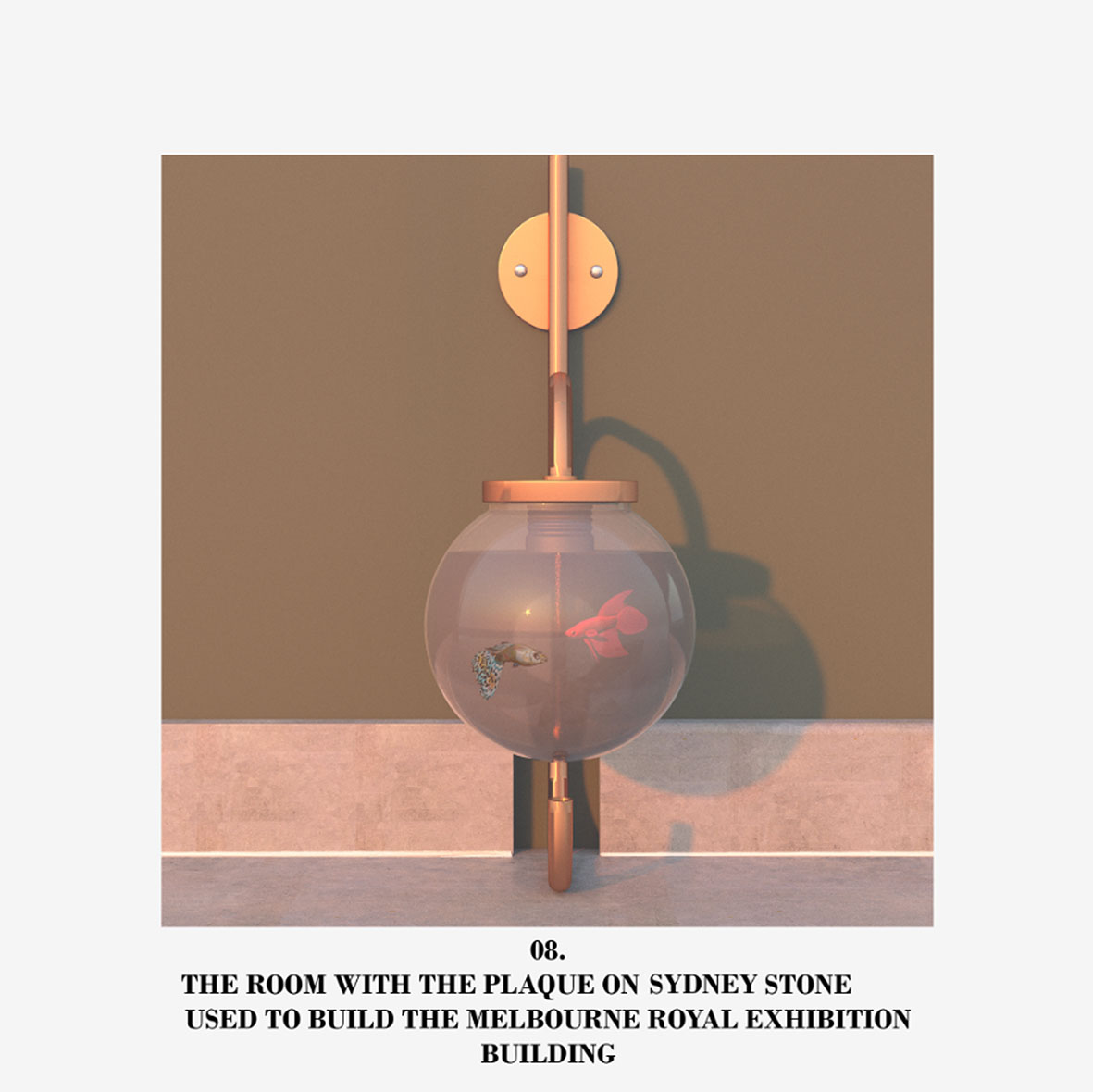

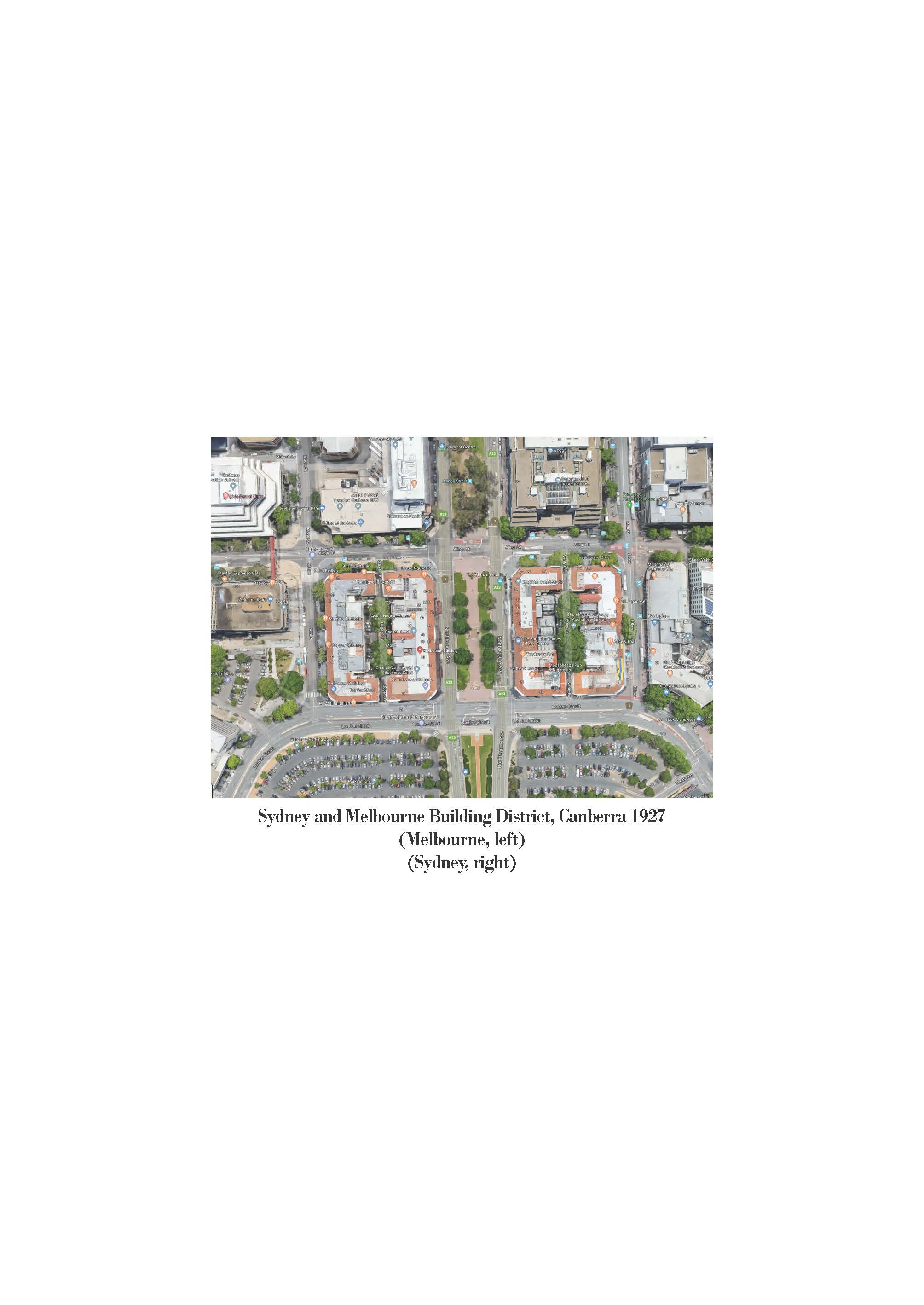

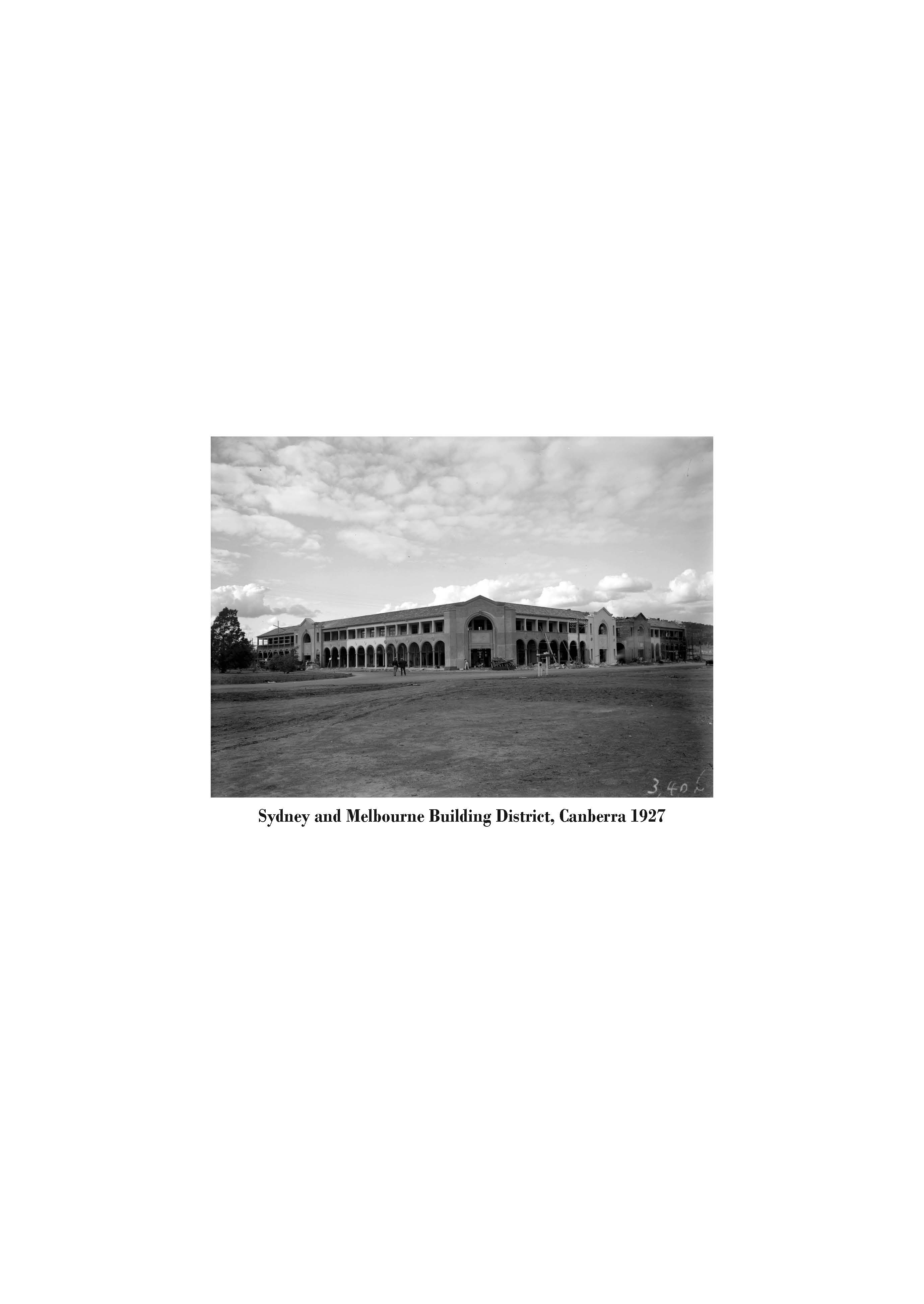

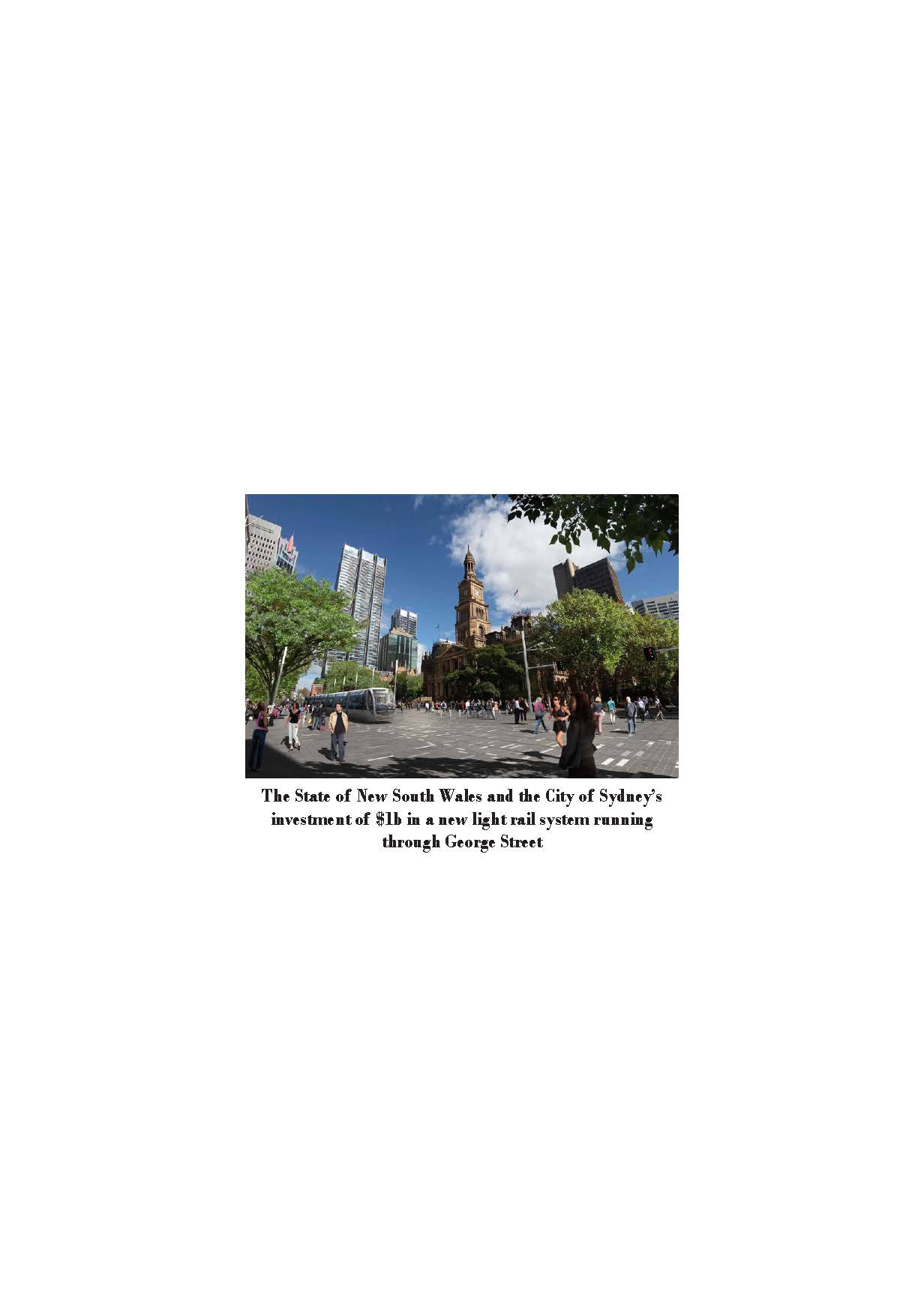

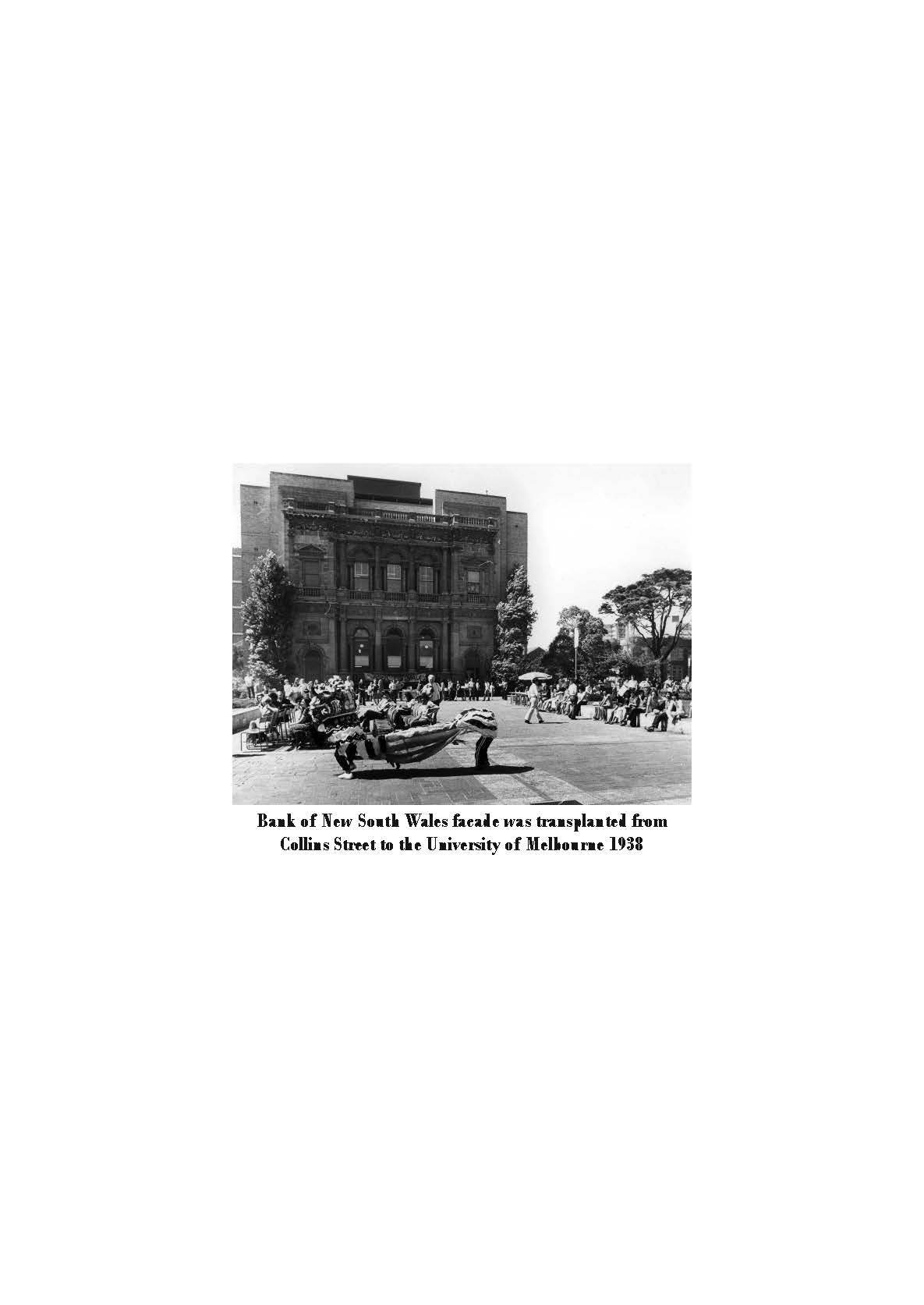

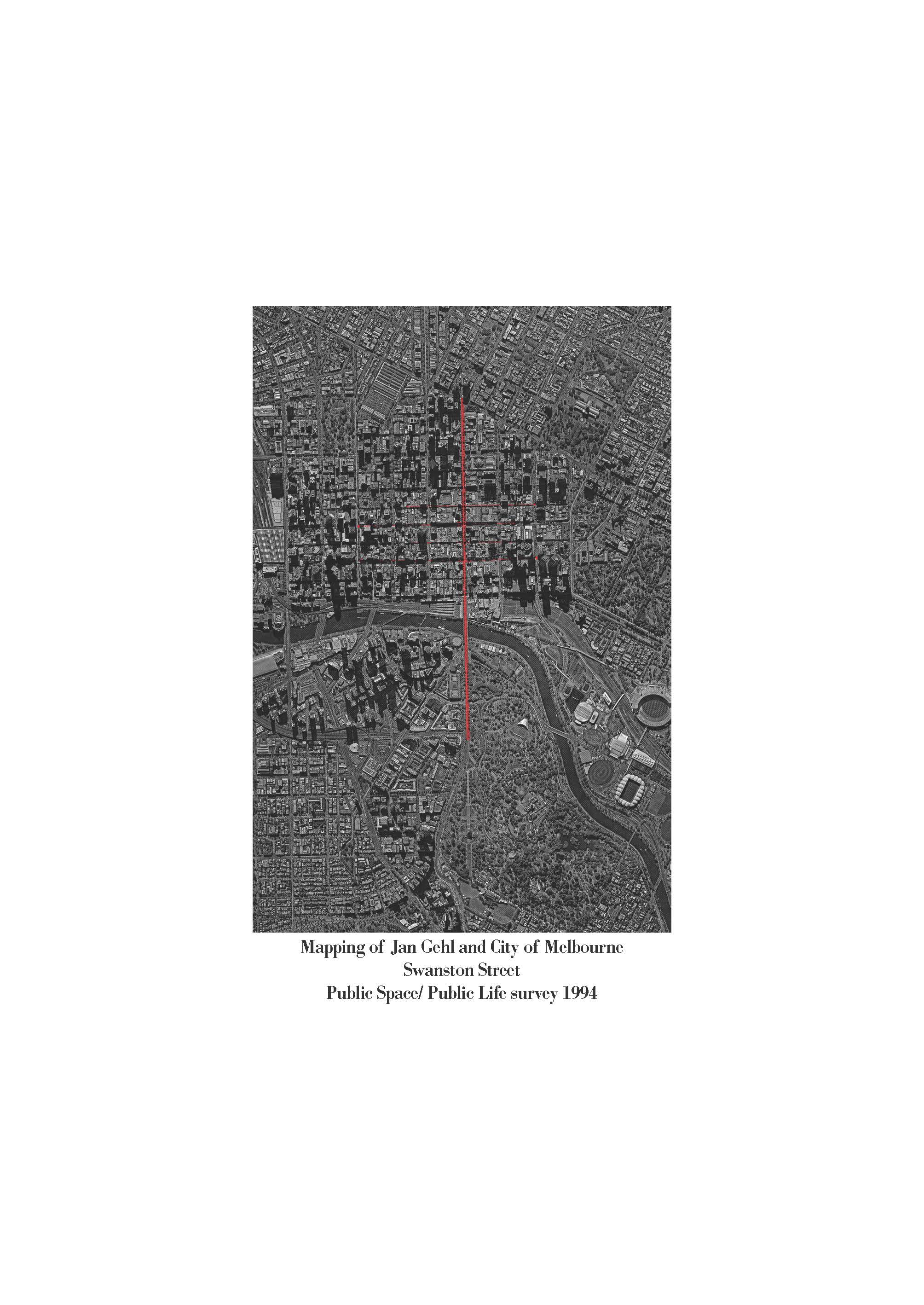

Sfumato exhumes itself where, in the mermaid, the woman and fish become indiscernible. The confluence of tone, gradients and intensities become sub-semiotic marks in Sydney-Melbourne’s Ship of Theseus. In efforts to Melbournise Sydney, the City of Sydney has employed Jan Gehl to pedestrianize George street, much like Melbourne’s Swanston street. Another example would be the anxiety shown by the plaque outside the Royal Exhibition building. It reads: ‘This pillar of stone quarried from Stawell was placed here to express the in-dig-nation of the choice of New South Wales stone and to show the enduring qualities of local stone’.

This movement between the milieus of slippages proliferates a nervousness when the appearance of what is known disappears into what Derrida calls its ‘vanishing point’. It is what Anthony Vidler draws in Dark Space, “It is where I know where I am, but do not feel as though I’m at the spot where I find myself”. As Heygel puts it, in the recognition of another consciousness, “to become aware of the other is to become aware of the possibility of your own negation.”

Drawing what is known allows us to affirm a constant antithetical position to the other. We desire the isolation of things to prevent our assimilation, to enclose us within an absolute difference and to continue its propensity to be what it is

The case-study of Sydney-Melbourne assumes this titular schizophrenia on the site. Sydney and Melbourne become characters in a play, where the story of the two cities begin to operate procedurally, and one cannot deny the permission it has been granted from the other.

…

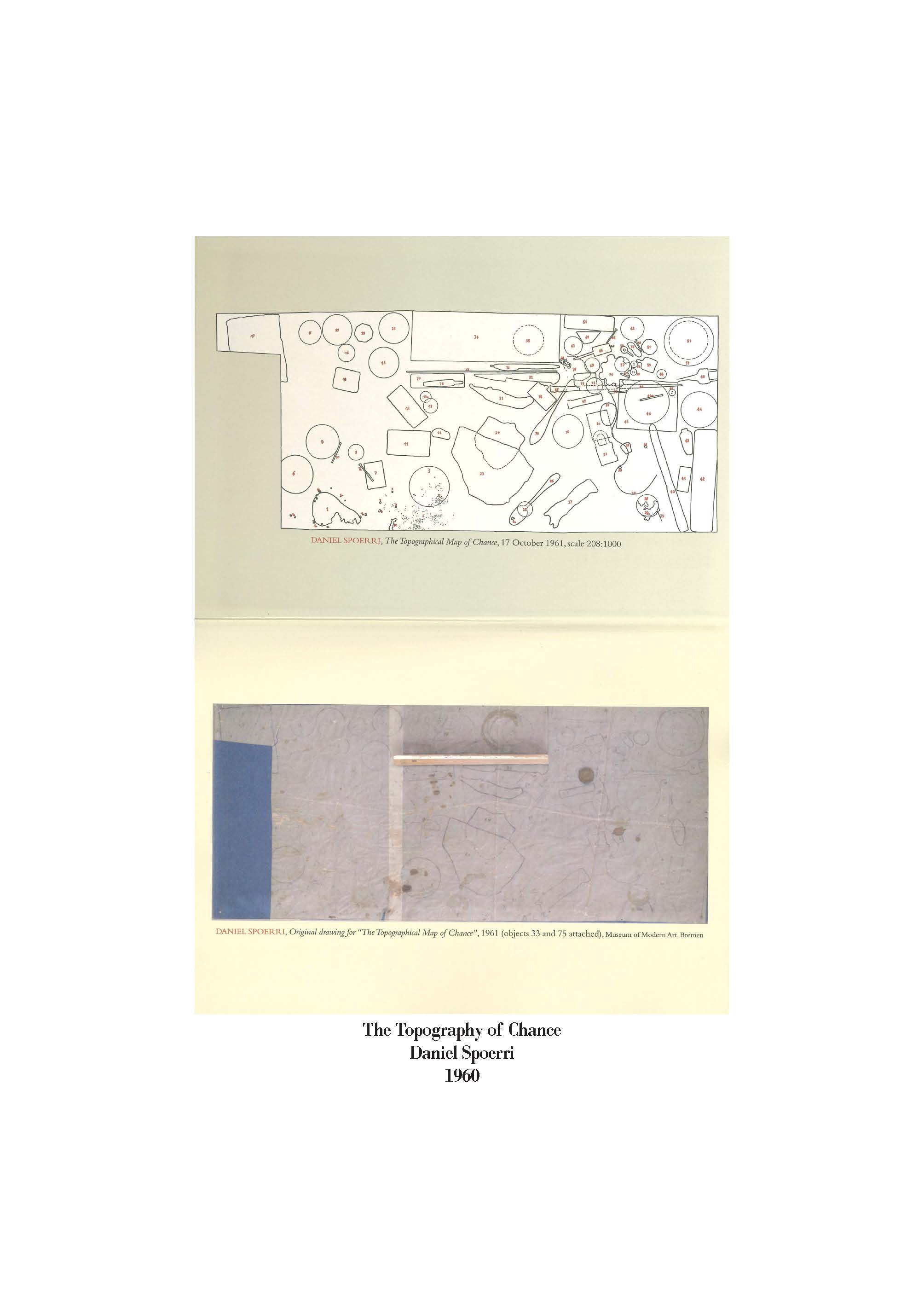

The pub’s existing geometry propagates itself outwards in a game of chance; alluding itself to Nietzsche’s dice-throw. It is not that many throws of the produces the repetition of a combination but rather the number of the combination which produces the repetition of the dice-throw. The building resolves the points of difference as it navigates this topography of chance.

On the ground floor, the Sydney Swans Hotel, ‘Home of the original Victorian Football Club’ sits next to Melbourne’s Rising Sun Hotel, ‘Home of the South Melbourne Swans’. In the other two corners lies the New Fosters Club Bar, ‘Home of the Rising Sun Football Club’, and Adelaide (For now)’s Emerald Hill Hotel: ‘Home of the Original Victorian Football club’. The four pubs on the ground floor share the same bar, which extends to a central kitchen, serving food to the pubs, the Deliveroo kitchens and Pizza Hut. If Difference is how things change, then all things are defined by the possibility of difference between them.

It is this chiaroscuro between the mechanisms of discernment which are most intensely visible, and those that are least visible which allows us to identify the lines of flight propagating from a singular point; which allow the Sydney Swans to maintain itself as ‘one club, two cities’, or; how the Rising Sun Hotel can exist as the home of the Sydney Swans in the middle of Melbourne. It is the invention of fog by the painter Whistle: without his vision fog did not exist.

Here, architecture is a device to register difference, operating in the recursive balance between sympathy and antipathy, between mechanisms of discernment and of sfumato. After all, each city has their own architecture, but architecture is also common to all cities. It describes how architecture allows, and it is as Gilles Deleuze says; “it explains how things grow, develop, disappear, and die, yet endlessly find themselves again” and that “the logic of life displays an excessive logic of difference through repetition. The centres of envelopment—the various mutations of folding—are the ‘mute witnesses to degradation’, but they are also the ‘dark precursors’, signs of life’s perpetual self-overcoming.”

The architectural condition explicates itself in this logic, taking the idea of symmetry and changing it for balance, taking asymmetry and changing it for movement. Truth here is made possible by repetition and excess, imagining the site as a resolution of potentialities which occur at the first throw of the dice. This condition locates itself at the chamfered edge of the pub where the only thing that separates Sydney and Melbourne is the hinge of a door. Sydney-Melbourne propagates in this singularity.

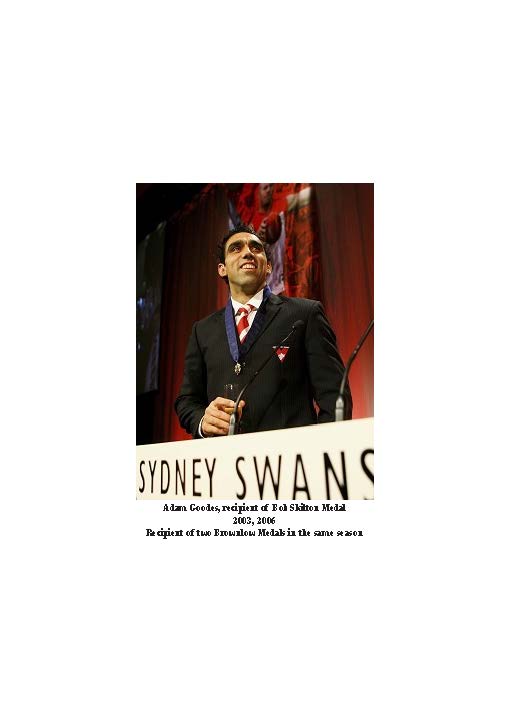

A gallery encompasses Sydney Swan’s best player and South Melbourne Swan’s best player. A knife is a knife is a knife. A lamp is a lamp is a lamp. In this way, Sydney and Melbourne will always be maintained by each other. Adelaide, for now, will be Adelaide, for now. And in the Foster’s bar, ‘likeness is not concerned with agreeing with ‘common sense’ or with defying it, but only with spontaneously assembling shapes from the world of appearance in the order given by inspiration.’

It is all these mechanisms working at once in aggressive symbiosis, between agonism and affirmation. The program list which embodies the confluence of strategies between the two cities, the recognition of material thickness and points of tension at which multiple forms of knowledge meet, and the allowance of architecture to maintain sympathy without engulfing one in the same, propagating and folding back within itself indefinitely.

It is the identity of things. The fact that they can resemble others and be drawn to them, though without being swallowed up or losing their singularity. Perhaps it is best understood in the story of Emerald Hill becoming Albert Park, Albert Park leaving to become South Melbourne, Cecil Hill becoming South Melbourne, Albert Park merging with Cecil Hill to become South Melbourne, and South Melbourne becoming what we now know as the Sydney Swans, or ‘the bloods’. In the end, it speaks to how we may see each other, and what it means for either city to accept my living there.

After all, the family dog is the family’s dog until it takes a shit on the carpet.

And I will never be entirely one, or the other

…

Before I moved to Melbourne, I took a drive to our old house between Star Street and the longer winding road called Fonti.

Two years after we moved out, Uncle Joe had passed away.

The drive by was slow, like looking through the window of the family’s house on a balmy Summer night; the fog which rolls in after the daylight has held on for far too long. It reminds me of the drive away in the taxi from my grandmother’s apartment in Hong Kong, always keeping my eyes open as my family slept, taking in the dense towers of pollution and noise, but a landscape just as familiar.

Now, on the corner of Star Street and Fonti Road sits a duplex in construction, and a site of only brown-grey Loam.

…